Taihō (大砲): Japanese Cannons and Artillery

Taihō (大砲): Japanese Cannons and Artillery

Cannons, and artillery in general, have been almost completely overlooked when it comes to Japanese warfare, despite the massive amount of works dedicated to the proliferation of guns in the 1550s, during the Sengoku period.

This attitude towards Japanese cannons have many reasons behind it (Turnbull I'm looking at you), and it was likely generated by Edo periods ideals boosted by the Tokugawa Shogunate, which by that time period had the monopoly on the production of said weapon.

However, during the 16th and early 17th century, the situation was quite different.

Yet it is fair to say that these weapons didn't play a significant role on field battles for a very simple reason: Japanese terrain.

Being a heavily forested and predominately mountainous island, carrying heavy artillery pieces throughout Japan must have been a nightmare, so the Sengoku period armies usually relied on smaller size hand held cannons which should be considered cannons instead of normal arquebuses.

However, the heavy pieces were used occasionally on naval warfare and especially in sieges during the second part of the 16th century, both by the defenders and the attackers.

It is also worth saying that due to the design and location of Japanese castles, cannons alone weren't able to guarantee the success of the invading army.

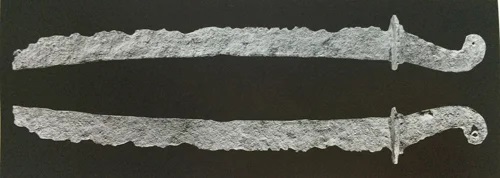

A Japanese breech loaders cannon, a very common design used during the Sengoku period.

Cannons have been used in several occasions in Japan: in 1558 they were fired from the coast of Bungo (the Otomo territory) to drive off an attack by "several hundred boats", (which implies that many guns had been made locally). In 1571 Oda Nobunaga placed an order with the Kunitomo gunsmiths for a gun that would take a load equivalent to 750 grams. Cannons were also fired from ships against the Nagashima garrison, and at the two battles of Kizugawaguchi in 1576 and 1578. They were used at the land battle of Noguchi in 1578, and by 1582 were being used in the provinces of Etchū and Noto. During the same time period, Maeda Toshiie wrote to his brother asking for twenty cannon balls.

In 1584 cannons, probably in the form of swivel guns, were fired from boats mounted offshore during the Battle of Okita Nawate on the Shimabara peninsula and during the Korean War (1590s) requests were sent back to Japan for cannon to help reduce the Korean castles.

Artillery was deployed at Sekigahara in 1600 and at the siege of Fushimi castle in the same year.

Most famously, according to the lore, as many as 300 cannons, including Europeans ones, were used during the Siege of Osaka in 1614.

The first "cannons" likely start to appear in Japan during the 14th century, and were probably based on Chinese models; not much is know about these weapons except that if anything they were incredibly rare and saw little usage at all.

A Japanese cannon, possibly a "hand held cannon", dated 1325.

Furankihō (フランキ砲): breech loaders cannons

One of the oldest Japanese furanki cannon.

The first true development of cannons in Japan happened during the 1550s thanks to the Nanban trade (南蛮貿易); the first two specimens of breech loaded cannons were introduced by the Portuguese missionaries to Ōtomo Sōrin (大友 宗麟). Each consisted of a heavy barrel on a swivel, and both were breech-loaders: the powder and shot being loaded into the top of the breech by a separate cylinder with a handle welded on, which is by no means as efficient as a muzzle-loader. These early European models were either called ishibiya (石火矢) or furankihō (フランキ砲), the latter likely influenced by the Chinese name of the same gun, folangji (佛郎機). Occasionally, they were also called kunikuzushi (国崩) by the Ōtomo clan, which means country destroyer.

The Ōtomo clan clearly had an advantage with the imports of cannons, since they started to used them for coastal defense in the 1558. They send a cannon in the 1560 to Ashikaga Yoshiteru and requested others in the 1560s to the Portuguese missionaries.

Although these cannons were often imported by the Europeans, many examples were still made locally.

A sketch of the same weapon.

These weapons were almost exclusively cast with bronze, although wrought iron examples existed as well, and could weight as much as 120 kg, while being 1.5 to 3 meters long.

The iron ones usually had the barrel reinforced with rings.

The breech cover was made of wood, and had the disadvantage that some explosive gas escaped along its seams, decreasing the reach and the power of the cannon.

Despite the inefficiency, the surviving examples could still fire a 70mm projectile that weighed 1.3kg, and the breech arrangement allow very quick reloading. Many of these guns were also mounted on swivels and used on warships.

They could also shot grapeshot instead of one single cannonball.

During the 1560s only the most powerful clan in western Japan owned such weapons, but they quickly discovered their limits: they were incredibly heavy, difficult to transport and used a lot of gunpowder, three factors that severely limited their utility in the mountainous Japan.

Moreover, being made of bronze, they could potentially fail and explode while shooting and they were also rather expensive to produce.

The Ōtomo after a quick retreat were forced to leave two cannons to the Shimazu at the battle of Mimigawa in 1578, because of their heavy weight.

Despite its limits, this model of cannon was quite popular in Japan and was used throughout the 16th and 17th century.

Two breech loaders bronze cannons mounted on a wooden stand while being loaded; on the left of the picture, you can see the chambers used to fire the weapon being prepared. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Harakan (破羅漢): muzzle loading cannons

After the introduction of European breech loaders cannons, the Japanese started to develop their own artillery, not only by copying the furanki design, but also by creating their own muzzle loading weapons.

These cannons are either called harakan or most famously ōzutsu (大筒); to add more confusion, this term refers to a in incredibly wide variety of guns, some of which are large caliber heavy muskets while other are much more akin to cannons. Just like the furanki, they could shoot either cannon balls or grapeshot, and even arrows. They were used to destroy gates, barricades, castles but also as antipersonnel weapon.

Two ōzutsu guns with their respective projectiles.

The first Japanese specimens recorded are two guns of 3 meters in length, capable of firing projectiles of 0.74 kg, which is the equivalent of 20 monme (匁). These were made by the Kunimoto's smiths in 1571 and were ordered by Nobunaga himself.

These guns were likely to be oversize teppō as far as their look was concerned, and were made of thick wrought iron instead of bronze. The choice of the material improved the strength and reduced the cost, but it didn't help with the weight. The muzzle loading provided a safer weapon, but on the other hand it was slower to reload.

Two very big gun versions of the ōzutsu mounted on wheels and covered with a special device in order to fire even if it's raining. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [1].

An ōzutsu gun mounted on a wooden stand with wheels. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Also, due to the usage of wrought iron, the caliber remained in the range of light to medium cannons. One of the heaviest gun of this type was made in Sakai in 1610, it was 3m long and weighed 135 kg.

An ōzutsu gun mounted on a wooden stand with wheels. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

The aforementioned style of oversize gun; indeed despite its look, the length and diameter of the barrel is the same of a medium cannon.

Shorter ōzutsu existed as well, and they were often fitted with a gun stock and fired like hand held firearms. The shorter versions were at the same time lighter and potentially stronger than their equivalent breech loaders counterparts, because of the muzzle loading. On the field, the gun versions were fired either by using some form of tripods or by letting the weapon resting on the shoulder of another soldier.

Two reenactors operating a long ōzutsu.

A very ingenious way to achieve elevation with one of those big guns; on the far right, a rope is tied to a tree and the gun is suspended. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

On the other side of the spectrum, larger and heavier guns existed as well. Instead of having a gun stock, they were encased by wood and rested on a wooden sliding mount capable of absorbing the recoil and they were fired like touch hole cannons. These weapons are also called taihō (大砲) in order to distinguish them from the hand held cannons.

Two medium size taihō, one loaded with a heavy steel arrow.

To carry these guns on the battlefield, it seems that most of them were essentially mounted on a cart pulled by oxen.

According to some Japanese manuals of the Edo period, they were also fitted with wheels in a similar fashion to European cannons.

Two big taihō cannons operated under heavy rain. They are mounted on a solid wooden stand with wheels. From武道藝術秘傳圖會 [1].

On the other hand, for siege purposes, which was the main role of these weapons, sometimes they were tied on to a pile of rice bales stuffed with sand, or mounted on solid wooden stand like the ones used on European ships of the same period.

Two medium size taiō mounted on wooden stands whit wheels similar to the ones used in European ships. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Elevation was achieved by ropes, which were either rolled under the barrel of the weapon or used to suspend the gun; sometimes other wooden stands were used.

More often than not, these stationary weapons and their users were often protected by iron shields or taketaba (竹束).

Two types of coverage; on the left, taketaba and on the right a iron shield mounted on the cannons. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Some of these cannons were able to fire projectiles of 5,6 kg, with the heaviest ones capable of shooting projectiles of 11,25 kg, 13,13 kg and most impressively 18,75 kg cannon balls.

These guns had usually a very short but thick barrel, raging from 0.07 to 0.50 meters, although longer examples existed as well.

Two medium size taihō, one loaded with a heavy steel arrow.

To carry these guns on the battlefield, it seems that most of them were essentially mounted on a cart pulled by oxen.

According to some Japanese manuals of the Edo period, they were also fitted with wheels in a similar fashion to European cannons.

Two big taihō cannons operated under heavy rain. They are mounted on a solid wooden stand with wheels. From武道藝術秘傳圖會 [1].

On the other hand, for siege purposes, which was the main role of these weapons, sometimes they were tied on to a pile of rice bales stuffed with sand, or mounted on solid wooden stand like the ones used on European ships of the same period.

Two medium size taiō mounted on wooden stands whit wheels similar to the ones used in European ships. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Elevation was achieved by ropes, which were either rolled under the barrel of the weapon or used to suspend the gun; sometimes other wooden stands were used.

More often than not, these stationary weapons and their users were often protected by iron shields or taketaba (竹束).

Two types of coverage; on the left, taketaba and on the right a iron shield mounted on the cannons. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Some of these cannons were able to fire projectiles of 5,6 kg, with the heaviest ones capable of shooting projectiles of 11,25 kg, 13,13 kg and most impressively 18,75 kg cannon balls.

These guns had usually a very short but thick barrel, raging from 0.07 to 0.50 meters, although longer examples existed as well.

These weapons were quite popular during the late 16th century, due to their modest size and weight.

Two different styles of medium/small size taihō. These styles were the most popular ones during the Sengoku period.

Other cannons built in Tosa weighed 60 kg and were capable of firing a 0.788 kg projectiles of 54.4 mm, and others could fire projectiles of 1.125 kg and 57.6 mm for 2.5 km.

Occasionally, these cannons were made of bronze too rather than wrought iron.

Two different styles of medium/small size taihō. These styles were the most popular ones during the Sengoku period.

Other cannons built in Tosa weighed 60 kg and were capable of firing a 0.788 kg projectiles of 54.4 mm, and others could fire projectiles of 1.125 kg and 57.6 mm for 2.5 km.

Occasionally, these cannons were made of bronze too rather than wrought iron.

A small size cannon made of iron. Cannons like these were usually encased with a wooden structure.

Another wrought iron medium size taihō.

A very big bronze cannon; although this is from a later period, this was essentially a 16th/17th century Japanese cannon design.

To add even more confusions, if the same weapons, namely the ōzutsu either with a gun stock or in the form of a taihō, is used to shoot arrows, it is usually called bōhiya (棒火矢), hiyataihō (火矢大砲) or hōrokuhiya (焙烙火矢): however, despite its many names, the only big difference is the projectile.

A small hiyataihō; see how the ropes are used to acquire elevation. Small cannons like this one were incredibly popular.

Instead of a cannon balls, large and big incendiary arrows similar to rockets were used; they were ignited by lighting a slow burning fuse made from incendiary waterproof rope which was wrapped around the shaft. Once they hit the target, the fire propagate nearby since inside the head there was a charge of gunpowder.

These projectiles were deemed to be capable of setting enemy ships on fire and so were used more often than not on naval warfare.

Three incendiary arrows, also know as hiya (火矢).

However, the arrows weren't always incendiary ones; they could have been a cluster of normal arrows or a very big one, like a harpoon.

An old sketch from a Edo period book of a hiyataihō mounted on a pile of rice bales.

Other types of artillery

Although the main cannons used during the Sengoku era are the ones described above, few oddities and rare design existed too.

It is important to say that imported European cannons were still prized and acquired especially by Tokugawa Ieyasu; he used several English and Dutch cannons during his Osaka campaign.

Even before that, the Europeans had established some foundries in Kyushu during the 16th century.

These were likely culverin, sakers and other similar European cannons, both breech loaders and muzzle loading designs. The Portuguese and later one the Dutch cast many heavy cannons during the late 16th and early to mid 17th century; some of them were as heavy as 240 kg.

A very famous and heavy Japanese cannon owned by Tokugawa Ieyasu, made by the Kunimoto smiths in the early 17th century. This gun was made of wrought iron, it is 3 meters long, it weigh 1542 kg and fired 5.6kg cannon balls. It is also know as Ieyasu no Taihō (家康の大砲) and it was used during the Osaka siege.

Another style of artillery which never really saw battlefield usage are mortars; these guns were cast by the Dutch in the 1630s.

However, after a demonstration of eleven shots of said weapon, the Japanese weren't particular impressed because none of them was able to hit the target and few shots exploded too close to the operators, wounding them. Nevertheless, they still acquired the weapons, although Japan didn't see any type of battle for the next 200 years.

However, after a demonstration of eleven shots of said weapon, the Japanese weren't particular impressed because none of them was able to hit the target and few shots exploded too close to the operators, wounding them. Nevertheless, they still acquired the weapons, although Japan didn't see any type of battle for the next 200 years.

Two mortars on the left with their shots being made on the rights. From 武道藝術秘傳圖會 [2].

Another very important and often totally overlooked form of artillery are wooden cannons, known in Japan as mokuhō (木砲).

These were essentially cannons made of wood instead of iron or bronze; additional reinforcements to the barrel were required, like a series of thick ropes or iron rings. Although quite primitive, these devices worked and were a very cheap and light alternative to the mainstream cannons. However, due to the material, said cannons were incredibly weak and unsafe so they were usually used to fire a couple of shots and then thrown away.

These types of weapons were also used during the 19th century in Japan and in other part of the world as well.

They were used to shoot cluster of arrows, grape shots or cannon balls, but were also used to project smoke in the air.

Two 19th century wooden cannons; similar ones were used during the Sengoku period.

These were essentially cannons made of wood instead of iron or bronze; additional reinforcements to the barrel were required, like a series of thick ropes or iron rings. Although quite primitive, these devices worked and were a very cheap and light alternative to the mainstream cannons. However, due to the material, said cannons were incredibly weak and unsafe so they were usually used to fire a couple of shots and then thrown away.

These types of weapons were also used during the 19th century in Japan and in other part of the world as well.

They were used to shoot cluster of arrows, grape shots or cannon balls, but were also used to project smoke in the air.

Two 19th century wooden cannons; similar ones were used during the Sengoku period.

This was everything as far as Japanese cannons in the 16th and 17th century are concerned; for any question feel free to ask and if you like the article, please feel free to share it. Thank you!

Gunbai

Wait a minute, I thought Kunikuzushi were quite heavy (something in the range of 450 kg)? And it is said that the Tekkousen mounted three of them?

ReplyDeleteNo doubt that heavier version existed as well indeed, especially if mounted on ships; the atakebune usually had 3 of them.

DeleteThis replica is around 300 kg:

http://sorin-hinawa.lolipop.jp/swfu/d/s_PAP_0346777.png

Tremendous work as always, Gunsen! : )

ReplyDeleteI believe I actually saw some versions of the Taiho being represented in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Kudos Hidetaka Miyazaki and his team at Fromsoftware doing deep intricate research to find that there is more to Samurai warfare then just their famous Katanas.

Thank you so much!

DeleteVery nice article as always.I know very little about Dr Turnbull what sort of false claim does he assert

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteAbout Turnbull, his old works claim that the Japanese had difficulties in casting bronze cannons (despite big and heavy bronze bells being cast regularly) and that the Japanese cannons were of low quality and not too powerful, more or less (which again is a very bold statement that is not backed up by any sources as it is common in his old works).

For example, T. Conlan gives another analysis on Japanese artillery of the 16th century, and that was the one I used for this article.

This reminds me of Princess Mononoke,if i am not wrong Lady Eboshi gun was called an Ishibiya

ReplyDeleteYes indeed; usually cannons or large caliber guns have that name, while normal firearm are normally called tebiya (手火矢)

DeleteWill you ever talk about japanese castles? Love them, and there is a myth that they served as palaces and pavilions rather than fortresses.

ReplyDeleteCastles are still work in progress in my study list, but I will absolutely talk about them in the future!

DeleteDo we have any records on the range of such cannons?

ReplyDeleteWas the Ieyasu no Taihō the cannon capable of launching 18kg projectiles?(Thats pretty impressive, but of course, the range must be considered)

The Iyeasu's cannon was able to fire 5,6 kg projectiles; the range of those guns is estimated to be around 1-2.5 km but don't quote me on that. Unfortunately we don't have precise data on that.

DeleteGreat article as always!

ReplyDeleteAgain I would like to ask a question outside the topic of the article.

Relatively recently I was reading about the sakoku and in several texts mention that 2/3 Portuguese galleons tried to end the sakoku by force in 1647 attacking Nagasaki, but were rejected. In some parts they mention a massive blockade made by the Japanese and in others they simply mention that they were not able to subdue Nagasaki. Do you know something about the subject or do you have more information about it?

Thank you very much!

DeleteAbout that episode, is the first time I heard of it. There are some documents indeed but it was a simple diplomatic mission done by the Portuguese.

The Japanese ammassed an army to impress them and to show the power of the Shogunate, and also to avoid any possible invasion of other ships.

At the end of the episode, the two galleons left without any troubles and without the permission to trade.

Oh, for some reason I expected something more bombastic. Slightly disappointing ... Or no, I suppose the fact that nobody has died is something to be happy about (but it's not so much fun when you read it 400 years later)

DeleteWell, after all after the 1640s, there were no conflicts at all in Japan and the Shogunate was very keen on peace and harmony

DeleteThis will likely be very, very difficult, but do you believe it to be possible to write about the 石弾きcatapult? While likely not in use during the samurai's existence, it was apparently mentionned in the Nihon Shoki in the weapons given by the Korean king to Empress Suiko. I don't know a lot about it, so here's the book (Japanese) I found it in:

ReplyDeletehttps://books.google.co.jp/books?id=pt5DDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT286&dq=%E3%81%84%E3%81%97%E3%81%AF%E3%81%98%E3%81%8D+%E6%8A%95%E7%9F%B3%E6%A9%9F&hl=ja&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiTy-u33P_hAhUS8LwKHRwsB9IQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=%E3%81%84%E3%81%97%E3%81%AF%E3%81%98%E3%81%8D%20%E6%8A%95%E7%9F%B3%E6%A9%9F&f=false

Hi!

DeleteWell yes, it is possible to write an article about it although the usage of catapults (which has many name in Japanese) in Japan was very limited, and it was used during Samurai times. I will surely write about it, although I have to say it wasn't anything impressing compared to the ones used in China or in Europe.

Anyway, the "catapult" you are referring to which is mentioned in the Nihon Shoki is veri likely to be a type of ballista/crossbow used from the Kofun up to the Heain period which is called Oyumi. It was said that this weapon was capable of launching stones too, and despite the fact that we do not know a lot about it, I have an article about crossbows usage in Japan:

http://gunbai-militaryhistory.blogspot.com/2019/01/dokyu-japanese-crossbow.html

Thank you a lot for your response! It's truly a shame that so little is known about Japanese aryillery/siege weapons. If you ever do write about the usage of catapults/mangonels in Japan, I will read it just as eagerly as I read your other articles, especially since the beauty of your blogs lie in the fact that you shed light on aspects of Japanese warfare otherwise unknown (I won't lie, a lot of things mentionned here were unknown even to a native Japanese like me). Please keep up the good work, I'll be looking forward!

DeleteThank you so much for your inspiring words! I will write an article about that for sure; I think that it is good to focus on those less known features because the internet is already full of fantastic places for Japanese swords, for example, while very little attention is dedicated for the true weapons that changed Japanese history, like those cannons.

DeleteThere are still a lot of articles to write and I'm looking forward to write them ;)

I'm also very happy to have at least a Japanese reader; I'm glad to know that my efforts are worth it! どうもありがとう!

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI don't know why this comment was removed, because I think it was very interesting (It might be my fault because recently I've screwed up a little with few comments, and if this is the case I apologize); I'll report it and if the author decides that he doesn't want to have it again I'll delete it.

DeleteOriginal comment:

"actually, the portuguese matchlock more known as "tanegashima" was borrowed from india during the portuguese conquest of goa...

The quote comes from a letter that Albuquerque dispatched to King Manuel I of Portugal (d. 1521) while in Goa, on the southwest coast of India, in the year 1513. Albuquerque states:

"I also send your highness a Goan master gunsmith; they make guns as good as the Bohemians and also equipped with screwed in breech plugs. There he will work for you. I am sending you some samples of their work with Pero Masquarenhas."

I could talk a lot more about this if you're interested.

P.S. i am a portugese myself "

It is indeed true; the creation of Japanese and arguably of Chinese arquebuses was a direct adoption of Portuguese guns specifically made in Goa.

DeleteThe Chinese acquired them in the 1520s if I recall correctly and after that they spread all over East Asia. They arrived in Japan too likely thanks to Woko pirates and then later on they were also brought by the Europeans themselves in the 1540s.

DeleteI meant the Japanese matchlock came from India through Southeast Asia decades before 1543 and not directly from Portugal. The arsenal of Goa actually improved the arsenal in lisbon....

Albuquerque further reports that they/local indians had become “our masters in artillery and the making of cannons and guns, which they make of iron here in Goa and are better than the German ones.”

goan gunsmiths were sent from India to portugal and to work in the arsenal in lisbon. also the ming chinese describe the Vietnamese, Turkish and Japanese matchlocks better than the European one

the Indian subcontinent was already undergoing a gunpowder revolution in the 15th century before Babur's invasion employing warfare in the Ottoman style, in fact it is very likely that the proto-matchlock had been invented in the Islamic world as well as in the western world, the Ottoman empire had as major European enemies in the second half of the 15th century: hungary , italy and spain and curiously they were the first to widely use the matchlock, arquebus and matchlock are two different things, arquebus was originally a firearm without trigger mechanism used in central europe and after the implement of the matchlock trigger continued to be called arquebus

-although the word arquebus in modern military literature is more like an anachronism describing everything that came after handgonne in the 15th and 16th centuries, keep in mind that the musket (born in italy) was originally a type of arquebus that became dominant on the European battlefield.

-Battle of Cerignola: Marks the first military conflict in europe where arquebusiers played a decisive role, it was won by spain, a southern power

-The arquebus was used in relatively high ratios by the Ottoman army against the Hungarians in the mid-15th century,and then in Hungary under king Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490); every fourth soldier in the Black Army of Hungary had an arquebus.

- the Indian subcontinent especially the Bengal region was the world's largest saltpetre producer and refiner, no bengal = no english east india company, not to say the Congreve rocket was based directly on Mysorean rockets, rockets demand a lot of gunpowder and Europe produces very little saltpeter. Europeans did not abandon rocket artillery altogether and continued to test it since the Middle Ages (for example: Kazimierz Siemienowicz), they only had a certain scarcity of resources, which immediately led to little emphasis and economic prefrences

I particularly think there is a huge lack of asian studies (that could help japan to understand itself) by asian nations (emerging economies do not invest in anything that produces no immediate financial return, and even when that happens, there is still a certain Eurocentric reluctance to accept, it took decades for joseph needham to be an authority and laureate in the west ).... what makes the typical and boring dialectic, when something is not Western and is in non-Western lands, can only be 3 things: Westerners were there, myths by local religions or aliens

That's absolutely correct, the mathcloks arquebuses that arrived in Japan were made in Goa, not in Europe and as I have wrote in my article about gunpowder weapons in Japan, it was a slow process that started before the 1543 mainly due to Woko rather than European traders.

DeleteAlso thank you for all the insights about early gunpowder weapons; I didn't know all of that!

It is indeed a shame that there are few studies that deal with this topic in South East Asia.

Asia as a whole.

DeleteThe first matchlock that arrived in Japan through Southeast Asia does not have to be exactly from Goa. Goa was an insignificant place conquered by the Portuguese in India and the portuguese were more like a pirate faction. It took until the eighteenth century for Western imperialism to become a real threat to the great powers in Asia and contrary to the common myth, catholic proselytism was one of the smallest reasons for the tokugawa shogun to bar the foreign trade.

Excellent article!

ReplyDeleteI’m a big fan of your blog and find it very interesting. On a few of your posts you have written that the early stages of the Sengoku Jidai had smaller armies compared to later stages of the period. I was just curious if you had any numbers on the size of armies in the early, mid and later stages, so I could get an idea of the size difference.

Thank you so much!

DeleteRegarding your question, it really depends on the size and wealth of the clan rather than the time period, although during the early Sengoku there weren't the huge clans of the later period, so this is why on average you have small armies in the early Sengoku.

But I can give you an educated guess:

During the 1500s-1530s armies would have been made by 1000 -10 000 men.

1530s-1560s we start to se big armies with 20 000 or even 40 000 men.

During the late Sengoku in the 1560s up until the 1600 you have the very big armies of the great Daimyos that could count as many as 120 000 men like at Sekigahara.

That make me interested to know how large an army could Japanese clans field.Especially outside the Sengoku Period.

DeleteIn Wikipedia entry on Onin War:

Hosokawa's Eastern Army of about 85,000 and Yamana's Western Army of about 80,000 were almost evenly matched when mobilized near Kyoto.

How often do they field such army size?

It really depends on the time period but as far as the Onin war was concerned, the numbers are easily explained by the fact that the two armies were a coalitions of several clans; for example, inside the Hosokawa side there were also the Hatakeyama and the Shiba as well as many other clans.

DeleteEven the Shogunate itself was involved; this picture illustrates all the clans and provinces involved in the war:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ed/Ounin_no_Ran_1467.png

The blue ones are the Eastern army clans, the yellow the Western ones and the green the ones which eventually changed side during the war. Half of Japan was involved, and this is the very reasons why when the war ended and so many resources were lost forever, and why the Sengoku period started.

So these big armies existed only in the time frame of the Onin war and at the end of the 16th century.

What is the muzzle velocity of the ozutsu?

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately I don't have such data, I wonder if anyone has ever measured that.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

Delete5ft per second from YouTube comments

Deletehttps://youtu.be/Jf9jVxFaKtA

Average speed of most Japanese matchlock is a 330m/s to 480m/s depending on size and grain of the bullet

Deletehttps://m.blog.naver.com/karancoron/221162607612

Could the Japanese have had contact with gunpowder before the Mongol invasions?

ReplyDeletefocusing on northeast asia. But mentioning briefly jin-song wars, five dynasties and ten kingdoms period, battle of ain jalut and wuwei bronze cannon as examples of the non-mongol spread of primitive gunpowder weapons from china proper

-heilongjiang cannon

-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byeolmuban

"Ballistic/Cannon gunners called Balhwa (발화, 發火)"

this is at least 1 century before the Mongol invasions

- the song-kamakura trade:

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/91cc/034d461d30387b21f0eb1f55c124259ee1de.pdf

"in return for imports of Japanese sulfur, timber, and

gold"

"the restructuring

of Sino-Japanese maritime trade, which became primarily an exchange

of Chinese bronze coin and ceramics for Japanese sulfur, timber, and

gold"

"China consisted of bulk

commodities such as sulfur, timber, and mercury. Chinese imports of

Japanese sulfur for military purposes were substantial enough for one

historian to refer to the Sino-Japanese trade of this era as “the sulfur

road.”

Japanese had their own domestic production of sulfur in order to feed china? From the economic point of view this makes no sense since Japan was not a colony of china. At most we could say Chinese foreign consumption exceeded more than Japanese domestic consumption over time, which meant the Japanese would have started extracting it to satisfy themselves ..... plus on the same link in PDF format you can find: Japanese exporting swords and armor

"Japanese artisanal crafts—including swords, armor, fans, lacquer,

and mother-of-pearl handicrafts—were held in high esteem in China". Obviously japanese armor and swords appearead first to satisfy the japanese themselves

And yes sulfur took a long way before becoming one of the top 3 ingredients of gunpowder. So maybe there was a sulfur consumption in japan but it wasn't for military purposes at all but alchemy just like the things used to be in china, whatever...

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mōko_Shūrai_Ekotoba.jpg

Could the thunder crash bomb have been thrown from the Japanese side? the painting suggests yes, while the dominant historiography no..... It is also important to say fire arrows and incendiary bombs were the first primary uses of gunpowder warfare and both things are well mentioned in the 10th-century china/five dynasties and ten kingdoms period...

Sorry, I forgot to comment that it is very curious how the sulfur road coincides with the late-heian period conflicts such as genpei war, heiji rebellion, hogen rebellion and etc..... well there are endless examples of warfare in history when new resources and new technologies lose their usefulness with pacification .... so basically the demand for sulfur disappeared overnight in japan, and probably this endangered japanese wartime supply found new ways in maintaining itself and liquidating the surplus stock by supplying china... after all china was at a hundred years' war with jin dynasty

DeleteWell, genpei Josuiki talks about the use of fire oxen in the battle of kurikara (1183) with great efficiency, what would be impossible if not in the form of bombs (gunpowder)

Deletethe part where says about "exploding fire ox":

https://blog.press.princeton.edu/2016/05/11/tonio-andrade-animals-as-weaponry/

the scenes depicated in 源平倶利伽羅合戦図屏 at the bottom of the page:

http://kanazawa-burari.blogspot.com/2014/10/2.html

were apparently painted by 池田九華 in the 19th century..... a long time after the event

http://kankou.town.tsubata.ishikawa.jp/content/detail.php?id=42

Hi!

DeleteWell, it is an interesting theory but I would say with enough confidence that gunpowder based weapon didn't reach Japan prior to the 13th century.

For example, if you take the teppo bombshell exploding in the Moko Shurai Ekotoba, we know that according to stylistic and scientific investigation done by Dr. Conlan, that particular detail was added later and it is not mentioned in the written script of the scroll. So while it look weird and has a weird trajectory it shouldn't taken into account because of that. On the other hand, we know of those explosive shells because there are actual surviving artifacts recovered some years ago.

Moreover, we have records of those Japanese wars and there isn't a single mention of gunpowder weapons being used. It is true that some weapons technology was indeed lost during turmoiled periods, but we should have some records nevertheless: the Oyumi is a good example. The weapon technology was lost, we never found anything but there are written sources of it.

Also the fire ox tactic should be taken with a grain of salt. In my opinion, there are more effective usage of gunpowder weapons rather than a living hard to control bomb.

As far as we know, the poor animal was set on fire and that was already enough to create confusion against the enemy.

It might also be possible to have period scroll of that scene because iirc I have already seen oxen on fire depicted on Japanese scrolls.

Still, we might find new evidences in the future, but for now, I would say that there are no evidence to support that. But it is quite interesting nevertheless!

中国製の大砲というのは、応仁の乱でも使われた火槍のことかな?

ReplyDeleteそう思われますが、よくわかりません.

Delete本書には正確な説明がありません