Mongol Invasion of Japan (元寇): Part 1 - Some quick myths about the invasion (WIP)

Mongol Invasion of Japan (元寇): Part 1 - Some quick myths about the invasion (WIP)

A modern depiction of the Mongol invasion made by Kawashima Jimbei II

Edit: This is a work in progress, but I wanted to share some preview after having miss few months. Hope you will enjoy!

Some forewords from the author of this blog

Normally I don't make introduction about the blog itself in my articles, as I think about this project more like a timeless collection of articles dedicated to Japanese military history.

However, this time I feel that it is needed, and instead of making a separate post, I'll like to write something here, before getting to the article.

I think that for everyone, 2020 was a very rough year to get through for the global situation and the period of uncertainty we have ahead of us. As I'm writing this (July 2020), I didn't expect to find so much trouble in finding the time, the energy and the dedication to write something worth of the attention of the readers of this blog.

And the situation, plus a good amount of personal issues made me think about the role of this blog.

I always wanted to make the best out of my articles, without the arrogance to have the quality of historians nor people with years of knowledge on their back.

This blog was more like a place to share my notes and my ideas on topics related to Japanese military history, based on actual period and proper historical sources: but I'm not perfect nor qualified enough to have the ability of being always 100% right and while I wanted to write about everything concerning Japanese military history, I think that I should stick to the topic I'm more confident about, namely arms and armors.

Nonetheless, I really wanted to share my sources on other topics concerning Japanese military history, with the disclaimer that outside arms and armors topics, in which I do feel to be at least somewhat quite educated at this point, having spent 10 years of my life into that, I might not be 100% accurate.

In order to compensate for that, I've decided that whenever I'll cover these kind of topics, I will list my references; this won't elevate my article at any level above random stuff on the internet: it will always be a blog on the internet and I'll always invite people in double check the stuff I wrote, if they have the ways and the time to do so.

Lastly, as people might have noticed, I haven't wrote anything for months. That was quite weird for me, as I do enjoy writing on my blog - but this year, with its all weird features, made it very hard to have something ready every month, despite my efforts. This is also the reason behind this article: as I wanted to cover the Mongol Invasion since the beginning of this blog, and while I didn't have the time to dedicate something big and of quality, I'd rather start with a part 1 with some quick facts and myths before covering as much as I can.

This would be quite interesting, I believe, as I would target the "facts" that are taken for granted beneath the history of this conflict rather than the events itself, which are usually covered quite well in proper history books (Turnbull shouldn't be considered among those ones!).

I hope you will enjoy!

A section of the original scroll, from the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞).

Normally I don't make introduction about the blog itself in my articles, as I think about this project more like a timeless collection of articles dedicated to Japanese military history.

However, this time I feel that it is needed, and instead of making a separate post, I'll like to write something here, before getting to the article.

I think that for everyone, 2020 was a very rough year to get through for the global situation and the period of uncertainty we have ahead of us. As I'm writing this (July 2020), I didn't expect to find so much trouble in finding the time, the energy and the dedication to write something worth of the attention of the readers of this blog.

And the situation, plus a good amount of personal issues made me think about the role of this blog.

I always wanted to make the best out of my articles, without the arrogance to have the quality of historians nor people with years of knowledge on their back.

This blog was more like a place to share my notes and my ideas on topics related to Japanese military history, based on actual period and proper historical sources: but I'm not perfect nor qualified enough to have the ability of being always 100% right and while I wanted to write about everything concerning Japanese military history, I think that I should stick to the topic I'm more confident about, namely arms and armors.

Nonetheless, I really wanted to share my sources on other topics concerning Japanese military history, with the disclaimer that outside arms and armors topics, in which I do feel to be at least somewhat quite educated at this point, having spent 10 years of my life into that, I might not be 100% accurate.

In order to compensate for that, I've decided that whenever I'll cover these kind of topics, I will list my references; this won't elevate my article at any level above random stuff on the internet: it will always be a blog on the internet and I'll always invite people in double check the stuff I wrote, if they have the ways and the time to do so.

Lastly, as people might have noticed, I haven't wrote anything for months. That was quite weird for me, as I do enjoy writing on my blog - but this year, with its all weird features, made it very hard to have something ready every month, despite my efforts. This is also the reason behind this article: as I wanted to cover the Mongol Invasion since the beginning of this blog, and while I didn't have the time to dedicate something big and of quality, I'd rather start with a part 1 with some quick facts and myths before covering as much as I can.

This would be quite interesting, I believe, as I would target the "facts" that are taken for granted beneath the history of this conflict rather than the events itself, which are usually covered quite well in proper history books (Turnbull shouldn't be considered among those ones!).

I hope you will enjoy!

Gunbai

Introduction

Within Japanese history, the Mongol Invasion has always been associated with events of greater importance especially from a military history point of view.

It is one of the few astonishing Mongol defeat, and helped to create the nationalistic myth of the kamikaze (神風).

Within Japanese history, the Mongol Invasion has always been associated with events of greater importance especially from a military history point of view.

It is one of the few astonishing Mongol defeat, and helped to create the nationalistic myth of the kamikaze (神風).

Moreover, there is something extremely heroic in the narration of the conflict, as the islands of Japan struggled against the mighty invaders and were saved by divine intervention from a doomed future.

It is also a key event for many history books, both in Japan and for the Yuan dynasty: it was one of the last conflicts before the death of Kublai Khan and was behind the fall of the Hojo regency and the Kamakura shogunate in Japan.From a military history point of view the two invasions are often cited as key events for "modernize" the Japanese warfare of the period, which was apparently inadequate against the Mongols: although there is some little truth to that, it is a extremely broad generalization, and it's not supported by historical evidences of the late 13th and 14th centuries.

Despite being grounded in a historical narration of the events, the pop history version of the Mongol Invasions of Japan is quite far from the reality of the events that happened in Japan in the late 13th century, and within this article I would like to address some of these myths that are often portrayed when we talk about the "Mongol Invasion". This is a part 1 of a series which will cover the events of the invasions, however here we would have a broader look at both conflicts and I will try to explain why those facts that are often cited in the narrative of the invasions should be take into their historical context.

It is also a key event for many history books, both in Japan and for the Yuan dynasty: it was one of the last conflicts before the death of Kublai Khan and was behind the fall of the Hojo regency and the Kamakura shogunate in Japan.From a military history point of view the two invasions are often cited as key events for "modernize" the Japanese warfare of the period, which was apparently inadequate against the Mongols: although there is some little truth to that, it is a extremely broad generalization, and it's not supported by historical evidences of the late 13th and 14th centuries.

Despite being grounded in a historical narration of the events, the pop history version of the Mongol Invasions of Japan is quite far from the reality of the events that happened in Japan in the late 13th century, and within this article I would like to address some of these myths that are often portrayed when we talk about the "Mongol Invasion". This is a part 1 of a series which will cover the events of the invasions, however here we would have a broader look at both conflicts and I will try to explain why those facts that are often cited in the narrative of the invasions should be take into their historical context.

The "Mighty Invader": The force that invaded Japan

There is no doubt that the empire created by the successors of Genghis Khan was among the strongest, if not the strongest, military power of the period. Their conquest, tactics and historical reputation speaks for themselves and I'm quite sure that it is possible to find plenty of valuable information on their incredible war machine, so we won't cover much of it here.

The newly established Yuan dynasty that invaded Japan was also the one whom conquered and defeated the Song dynasty and ruled over the Goryeo dynasty in Korea.

Kublai Khan depicted on a hunting expedition, Liu Guandao, 1280.

Even if someone is not well versed in mongol tactics and warfare, the association with horse archery, skilled horsemen and feigned retreat should still be immediate. The mongols of the late 13th century were extremely proficient in the art of war, both when it comes to being skilled fighter but also in the often overlooked logistic and burocratic structures of their armies.

The organization, their tactics and the technology they employed by that time (being among the first to rely on gunpowder weapons thanks to the Chinese development of the century) were no doubt better and much more developed than the ones used by the Japanese of the period.

However, when we consider the two invasions of Japan, we don't find such a mighty invader.

The first thing to point out is that historical sources of the period seriously overstimate the troop strength of both factions in the conflicts.

In fact, if we have to give credit to the Yuan shi (元氏) when it comes to Yuan forces, the second invasion would be the largest historical amphibious operation up until the WWII, with the difference that the allied forces had to cross 20 miles 0f sea, while the two mongolian armadas 116 and 480 miles respectively.

The organization, their tactics and the technology they employed by that time (being among the first to rely on gunpowder weapons thanks to the Chinese development of the century) were no doubt better and much more developed than the ones used by the Japanese of the period.

However, when we consider the two invasions of Japan, we don't find such a mighty invader.

The first thing to point out is that historical sources of the period seriously overstimate the troop strength of both factions in the conflicts.

In fact, if we have to give credit to the Yuan shi (元氏) when it comes to Yuan forces, the second invasion would be the largest historical amphibious operation up until the WWII, with the difference that the allied forces had to cross 20 miles 0f sea, while the two mongolian armadas 116 and 480 miles respectively.

One doesn't have to be a historian to question the numbers of the invasion and see that there is clearly an evident exagerations.

Sadly, we lack decisive and reliable numbers, but on the other hand, we do have some estimations. The Japanese bakufu didn't recorded the exact number of troops but we have several second hand accounts.

According to Ishii Susumu and Kaizu Ichiro, the Japanese forces that fought in the invasions were in between 2300 and 6000 men. Yet it would be a mistake to consider all of these men to be mounted Samurai alone.

For instance, a guard duty register of the Izumi province in 1272 had a total of 98 warriors and only 19 of them were gokenin (御家人), while the rest 79 of it was made by low ranking retainers who fought on foot (heishi - 兵士).

Sadly, we lack decisive and reliable numbers, but on the other hand, we do have some estimations. The Japanese bakufu didn't recorded the exact number of troops but we have several second hand accounts.

According to Ishii Susumu and Kaizu Ichiro, the Japanese forces that fought in the invasions were in between 2300 and 6000 men. Yet it would be a mistake to consider all of these men to be mounted Samurai alone.

For instance, a guard duty register of the Izumi province in 1272 had a total of 98 warriors and only 19 of them were gokenin (御家人), while the rest 79 of it was made by low ranking retainers who fought on foot (heishi - 兵士).

This proportion is on the lower end of the distribution as the Izumi province wasn't among the most powerful ones, however it is very likely that horse archers Samurai were in between 10% and 25% of the total army that fought in both invasions, while the rest of it was made by lower rank retainers which fought on foot.

The famous and most important sources, the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞) give the idea that the Samurai forces with their retainers didn't consist of a large force, definitely under the 6000 mark.

Nonetheless the Mongol sources put the numbers of the defenders at 100 000 men, something that only around the time of the wealthiest daimyo of the Sengoku period in the late 16th century were capable of.

The famous and most important sources, the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞) give the idea that the Samurai forces with their retainers didn't consist of a large force, definitely under the 6000 mark.

Nonetheless the Mongol sources put the numbers of the defenders at 100 000 men, something that only around the time of the wealthiest daimyo of the Sengoku period in the late 16th century were capable of.

A section of the original scroll, from the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞).

Mongol sources on the other hand states that in the first invasion 15 000 men composed by Mongol, Jurchens and Han Chinese plus 8000 Korean soldiers, for a total of 23 000 men sailed for Japan.

However, given the nature of the operation and the presence of Han Chinese and Koreans, it would be wrong to think that the famous and skilled Mongolian horse archers made up the majority of the troops deployed in the war.

Nevertheless, the Mongol clearly states that they were outnumbered by their foes, so it is quite likely that only few thousand man reached Japan in 1274.

According to Japanese first hand account of the invasion, the mongol army that invaded Japan was made primarily by foot soldiers recruited in China and Korea, with Mongol horsemen acting as generals. Ironically, it is very likely that the Japanese army had much more horsemen than their mongolian counterpart.

Both Japanese and Mongol invasions seems to be exagerating the number of the Yuan forces, putting the entire armada at more than 100 000 men. While those numbers seems questionable, archeological findings of the second fleet clearly show that big war boats were deployed by the Yuan, which measure over 230 meters and thus could support such army. Still, the burden of such logistic feat would have been extreme even for the Yuan empire, so while it is very likely that the second invasion had more troops than the first one, it is hard to believe that they number more than 100 000 men.

On the other hand, other estimations for troop strenght exist as well in the literature.

For the first invasion, if we take into account additional korean sailors that might have partecipated in the fights as well, we could count an invading force of 27 000 - 30 000 men,while much more reliable account for the second invasion put the number of the two combined fleet at 70 000 men. Details of these troops, army and navy would be discussed in future article.

The main point of this section is to highlight that this wasn't the typical Mongolian army of the period. It wasn't made entirely by mounted warriors, which accounted for a very limited part of the troops, and the composition of different people inside the army, Han Chinese, Koreans, Jurchens and Mongol themselves made the comunication within the army extremely difficult.

In fact, it would be extremely flawed to call the entire operation a "Mongol Invasion" as the force was made by various people under the control of the Yuan empire.

Moreover, while the Samurai that fought to defend Japan were raised within a warrior culture that promoted martial attitudes, and had to actively looking for a fight in the war in order to get a compensation from the Shogunate, the same cannot be said for all the auxiliary troops that made the majority of the invaders army.

Those men lacked the discipline and the high status equipment of the Samurai they were fighting, but most importantly they were fighting in a foreing land, under the banner of their invader in their respective country.

However, given the nature of the operation and the presence of Han Chinese and Koreans, it would be wrong to think that the famous and skilled Mongolian horse archers made up the majority of the troops deployed in the war.

Nevertheless, the Mongol clearly states that they were outnumbered by their foes, so it is quite likely that only few thousand man reached Japan in 1274.

According to Japanese first hand account of the invasion, the mongol army that invaded Japan was made primarily by foot soldiers recruited in China and Korea, with Mongol horsemen acting as generals. Ironically, it is very likely that the Japanese army had much more horsemen than their mongolian counterpart.

Both Japanese and Mongol invasions seems to be exagerating the number of the Yuan forces, putting the entire armada at more than 100 000 men. While those numbers seems questionable, archeological findings of the second fleet clearly show that big war boats were deployed by the Yuan, which measure over 230 meters and thus could support such army. Still, the burden of such logistic feat would have been extreme even for the Yuan empire, so while it is very likely that the second invasion had more troops than the first one, it is hard to believe that they number more than 100 000 men.

On the other hand, other estimations for troop strenght exist as well in the literature.

For the first invasion, if we take into account additional korean sailors that might have partecipated in the fights as well, we could count an invading force of 27 000 - 30 000 men,while much more reliable account for the second invasion put the number of the two combined fleet at 70 000 men. Details of these troops, army and navy would be discussed in future article.

The main point of this section is to highlight that this wasn't the typical Mongolian army of the period. It wasn't made entirely by mounted warriors, which accounted for a very limited part of the troops, and the composition of different people inside the army, Han Chinese, Koreans, Jurchens and Mongol themselves made the comunication within the army extremely difficult.

In fact, it would be extremely flawed to call the entire operation a "Mongol Invasion" as the force was made by various people under the control of the Yuan empire.

Moreover, while the Samurai that fought to defend Japan were raised within a warrior culture that promoted martial attitudes, and had to actively looking for a fight in the war in order to get a compensation from the Shogunate, the same cannot be said for all the auxiliary troops that made the majority of the invaders army.

Those men lacked the discipline and the high status equipment of the Samurai they were fighting, but most importantly they were fighting in a foreing land, under the banner of their invader in their respective country.

If we use that lens, it is possible to see that the two factions involved in the war had completely different level of motivation: while the defenders had a dedicated warrior ethos that valued sacrifice and were willing to fight to deat, most of the invaders were ready to set sail to their native land as soon as possible.

Samurai Tactics - Mounted duels or Coordinated cavalry charge?

Another incredibly common and accepted idea is the the so called "clash of culture" between the much more advanced warfare developed by the Mongol in the mainland compared to the more romantic and ritualistic one used in Japan.

The topic of ikkiuchi (一騎打ち) or single combat is a stable of Japanese epic narrative, the gunkimono (軍記物), and thus it is natural that many "historian" incorporated such theme in their pop-history works; however, it is quite weird that those narratives were put outside their context.

According to the tradition of single duels, the two party that faced each other shouted their names with their lineage and then engage into a deadly and honorable duel, in Japan such duel would have been a mounted archery duel. I won't spend much time into going further into this one, as there is clearly already tons of material online plus the gunkimono themselves, and because it didn't exactly reflects the nature of Japanese warfare of the period.

Morevoer, it is also commonly assumed that Samurai fought among themselves into these weird honorable duels while their low ranking retainers acted as support units.

This myth however is not supported by the historical accounts of the period; among many of them, the famous Mongol Invasion scroll.The Samurai of the period fought into small units, and each unit was made by mounted archers belonging to the upper class and their followers on foot. The size of these units changed across the period and according to the wealth of each family.

The mounted archers were the striking arm of the unit, and often acted as shock troops, with ambushes and raid being the most common tactic deployed.

Those archers fought relatively close, according to the art of the period, although speaking of formation would be wrong. In this scenario, each Samurai used his bow to shoot one enemy at a time, but it would be wrong to call this whole context a duel.

The focus of the warrior wasn't solely aimed at one target though, and he himself could have been target of multiple enemies at once.

Each mounted warriors acted individually, but still inside his group and supported by his retainers on foot, so while everything was extremely fluid and definitely not coordinated, it's seems that some degree of cohesion was kept inside the group through the usage of battle flags, at least when the cavalry units charged. This interpreation is supported by the account of Takezaki Suneaga as well as period art.

A famous section of the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞), where you can see the men of Shiroishi Rokurō Michiyasu, charghing with his mounted squad against the Mongols.

Indeed by analyzing the written account of Suneaga, who was present at the battle, we do not find Samurai warriors trying to engage into honorable duels while shouting their names, but rather a consistent group of men on horseback charging forward with their knocked arrows;

Shortly before being wounded and shot in the famous scene depicting Suneaga falling from his horse, he goes on by saying:

Let us then charge!” and galloped forward shouting….My bannerman’s horse was shot, and he was thrown. Then I was wounded, as were three of my mounted retainers. My horse was hit as well, but just as I sprang from it, Shiroishi Rokurō Michiyasu, a shogunal vassal from Hizen province, came galloping in from the rear, with a sizeable force. The Mongol warband retreated toward Sohara. Michiyasu, whose mount was not yet wounded, plunged into the enemy ranks again and again. Had it not been for him, I would surely have perished. Amazingly, we both survived, and could act as witnesses for one another.

The famous scene depicted in which Suneaga is wounded; ironically, while it is possible to see a rudimentary form of explosive, this detail, according to a modern analyze of the scroll was added at a later date and thus we do not find a mention of such weapon in the specific account. On the other hand, we do know that those weapons existed and were used thanks to actual findings.

It's also wrong to believe that the Samurai only engaged among themselves or fought against their enemies if said people were "honorable" enough. There are plenty of accounts of low ranking retainers back stabbing other Samurai in order to save their lords or Samurai being killed by unsigned arrows, which were shot by low ranking retainers, as Samurai usually had their names written on theirs.

For the same reasons, the Samurai themselves didn't have issues in killing enemy on foot with their arrows or swords.

To summarize, we can see that the Samurai who fought in the Mongol invasion acted as small units of retainers, both mounted or on foot, and engaged the enemy with their bows while charging against it. This happened when field battles were carried by the two factions.

We do not see on the other hand, Samurai willing to fight on honorable duels while shouting their names, which to be fair would have been useless as the enemy couldn't speak their language, let alone hearing them while other people were killing each other!

There are no mentions of duels in the actual period fighting accounts; those are fabrications of epic narratives that were made to highlight the personal history and feats of a particular warrior.

The narrative of the accounts could also help us to see the pattern used by several hundred years in what we could call Samurai warfare, hence quick and fierce skirmishes, raids and unexpected attacks favoured by the skilled use of heavy horse archers, and a preference to pick scattered units; one Samurai named Yamada who defended Iki in 1281 used his most powerful archers to shoot dead three enemy mongols from higher distance.

Even when field battles didn't took place in 1281, the pattern was the same: usage of fortifications and accurate fire against scattered units, night boardings with smaller ships against the anchored navy and skirmishes which more often than not saw the Japanese warriors victorious against the unprepared Yuan-Goryeo armada.

The idle narration that depict the Samurai struggling against the much more superior and advanced Mongol army is quite far from the reality of the events, although has its own historical inception as we would see in the following paragraph.

Yet, with respect of both Japanese and Yuan-Goryeo sources, paired with a logical analysis of the invasions, we do see that the Mongols didn't enjoy any major tactical advantages when they clashed against the Japanese (despite being more advanced on paper in terms of logistical, technological and strategical point of view).

On the contrary, in 1274 they met fierce and stiff resistance to the point that the encounter with the Samurai of Shoni Kagesuke proved to be decisive for the Yuan retreat, as the commander of the army Liu Fu Xiang was wounded and Kagesuke praised by the Mongols themselves for his skill with the bow and horse.

In 1281, the construction of a wall on the beach of Hakata made the fleet unable to properly land, and their ships were constantly harrased by smaller Japanese boats.

The "Kamikaze" - The role of the typhoons in the Mongol Invasion

So one of the key elements of the pop version of these invasions, hence that the storms saved the country of the Rising Sun is simplistic and rather unrealistic, as the entire feat was doomed to fail from the beginning.

Yet the storms were real events, historically, although its importance was overly exagerated over the years by some historical sources themselves.

As historian T.Conlan commented on the whole episode, the thypoon that hit the fleet, while devastating on its own, was hardly a decisive factor on the defeat of the Yuan forces but more of coupe de grace on a dying enemy.

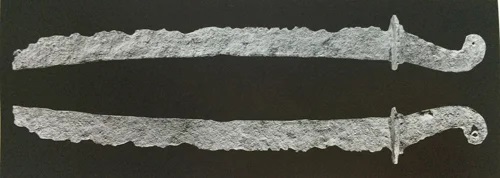

Sword's struggles - Did the Mongol brought the Japanese sword making to a change? (WIP)

Military "Evolution" or "Revolution"?- What the Mongol invasions brought to Japan (WIP)

Another incredibly common and accepted idea is the the so called "clash of culture" between the much more advanced warfare developed by the Mongol in the mainland compared to the more romantic and ritualistic one used in Japan.

The topic of ikkiuchi (一騎打ち) or single combat is a stable of Japanese epic narrative, the gunkimono (軍記物), and thus it is natural that many "historian" incorporated such theme in their pop-history works; however, it is quite weird that those narratives were put outside their context.

According to the tradition of single duels, the two party that faced each other shouted their names with their lineage and then engage into a deadly and honorable duel, in Japan such duel would have been a mounted archery duel. I won't spend much time into going further into this one, as there is clearly already tons of material online plus the gunkimono themselves, and because it didn't exactly reflects the nature of Japanese warfare of the period.

Morevoer, it is also commonly assumed that Samurai fought among themselves into these weird honorable duels while their low ranking retainers acted as support units.

This myth however is not supported by the historical accounts of the period; among many of them, the famous Mongol Invasion scroll.The Samurai of the period fought into small units, and each unit was made by mounted archers belonging to the upper class and their followers on foot. The size of these units changed across the period and according to the wealth of each family.

The mounted archers were the striking arm of the unit, and often acted as shock troops, with ambushes and raid being the most common tactic deployed.

Those archers fought relatively close, according to the art of the period, although speaking of formation would be wrong. In this scenario, each Samurai used his bow to shoot one enemy at a time, but it would be wrong to call this whole context a duel.

The focus of the warrior wasn't solely aimed at one target though, and he himself could have been target of multiple enemies at once.

Each mounted warriors acted individually, but still inside his group and supported by his retainers on foot, so while everything was extremely fluid and definitely not coordinated, it's seems that some degree of cohesion was kept inside the group through the usage of battle flags, at least when the cavalry units charged. This interpreation is supported by the account of Takezaki Suneaga as well as period art.

A famous section of the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞), where you can see the men of Shiroishi Rokurō Michiyasu, charghing with his mounted squad against the Mongols.

Indeed by analyzing the written account of Suneaga, who was present at the battle, we do not find Samurai warriors trying to engage into honorable duels while shouting their names, but rather a consistent group of men on horseback charging forward with their knocked arrows;

Shortly before being wounded and shot in the famous scene depicting Suneaga falling from his horse, he goes on by saying:

Let us then charge!” and galloped forward shouting….My bannerman’s horse was shot, and he was thrown. Then I was wounded, as were three of my mounted retainers. My horse was hit as well, but just as I sprang from it, Shiroishi Rokurō Michiyasu, a shogunal vassal from Hizen province, came galloping in from the rear, with a sizeable force. The Mongol warband retreated toward Sohara. Michiyasu, whose mount was not yet wounded, plunged into the enemy ranks again and again. Had it not been for him, I would surely have perished. Amazingly, we both survived, and could act as witnesses for one another.

The famous scene depicted in which Suneaga is wounded; ironically, while it is possible to see a rudimentary form of explosive, this detail, according to a modern analyze of the scroll was added at a later date and thus we do not find a mention of such weapon in the specific account. On the other hand, we do know that those weapons existed and were used thanks to actual findings.

It's also wrong to believe that the Samurai only engaged among themselves or fought against their enemies if said people were "honorable" enough. There are plenty of accounts of low ranking retainers back stabbing other Samurai in order to save their lords or Samurai being killed by unsigned arrows, which were shot by low ranking retainers, as Samurai usually had their names written on theirs.

For the same reasons, the Samurai themselves didn't have issues in killing enemy on foot with their arrows or swords.

To summarize, we can see that the Samurai who fought in the Mongol invasion acted as small units of retainers, both mounted or on foot, and engaged the enemy with their bows while charging against it. This happened when field battles were carried by the two factions.

We do not see on the other hand, Samurai willing to fight on honorable duels while shouting their names, which to be fair would have been useless as the enemy couldn't speak their language, let alone hearing them while other people were killing each other!

There are no mentions of duels in the actual period fighting accounts; those are fabrications of epic narratives that were made to highlight the personal history and feats of a particular warrior.

The narrative of the accounts could also help us to see the pattern used by several hundred years in what we could call Samurai warfare, hence quick and fierce skirmishes, raids and unexpected attacks favoured by the skilled use of heavy horse archers, and a preference to pick scattered units; one Samurai named Yamada who defended Iki in 1281 used his most powerful archers to shoot dead three enemy mongols from higher distance.

Even when field battles didn't took place in 1281, the pattern was the same: usage of fortifications and accurate fire against scattered units, night boardings with smaller ships against the anchored navy and skirmishes which more often than not saw the Japanese warriors victorious against the unprepared Yuan-Goryeo armada.

A group of Samurai boarding a Yuan-Goryeo ship with swords and polearms. From 蒙古襲来合戦絵巻.

The idle narration that depict the Samurai struggling against the much more superior and advanced Mongol army is quite far from the reality of the events, although has its own historical inception as we would see in the following paragraph.

Yet, with respect of both Japanese and Yuan-Goryeo sources, paired with a logical analysis of the invasions, we do see that the Mongols didn't enjoy any major tactical advantages when they clashed against the Japanese (despite being more advanced on paper in terms of logistical, technological and strategical point of view).

On the contrary, in 1274 they met fierce and stiff resistance to the point that the encounter with the Samurai of Shoni Kagesuke proved to be decisive for the Yuan retreat, as the commander of the army Liu Fu Xiang was wounded and Kagesuke praised by the Mongols themselves for his skill with the bow and horse.

In 1281, the construction of a wall on the beach of Hakata made the fleet unable to properly land, and their ships were constantly harrased by smaller Japanese boats.

Moreover, we do not see mentions of superior Mongol technology or tactics used effectively against the Samurai armies. Indeed, while the ships seems to have been equipped with form of trabuchets that launched primitive types of bombs called teppō, which scared the horses, and possibly the Mongol army carried some type of firelances, we do not have period or witnesses accounts of their usage, let alone sources claiming of their decisive impact on the battlefield.

The Mongols apparently didn't fought with en masse formations, but rather established portable shield walls - just as it was in the Japanese fashion - and defended their lines with bows and polearms. However they lacked their usual cavalry forces to counter the Japanese ones, given the naval nature of the invasion. The sources of the period also highlight the usage of gongs and drums to coordinate the troops, something that was new to the Japanese of the period whom rely on flags and colorful armors.

The Mongols apparently didn't fought with en masse formations, but rather established portable shield walls - just as it was in the Japanese fashion - and defended their lines with bows and polearms. However they lacked their usual cavalry forces to counter the Japanese ones, given the naval nature of the invasion. The sources of the period also highlight the usage of gongs and drums to coordinate the troops, something that was new to the Japanese of the period whom rely on flags and colorful armors.

A section of the scroll depicting Mongol forces in formation; said types of shield walls resembled those used in that period in Japan and didn't present major novelties for the Japanese.

When mounted Samurai charged against these formations, which were not extremely thight, were suddenly hooked by polearms and unseated by the foot infantries; however, many men managed to survive unscathed such ventures into enemy lines, like Shiroishi Michiyasu, and when the cavalry troops were numerous enough they usually break the enemy formation resulting into a enemy retreat at Akasaka in 1274, given the usually low morale of those troops.

Several Samurai were also able to collect enemy heads, implying that they had the upper hand against multiple enemies when faced into close quarter combat.

All of these sources when analyzed as a whole, describe both factions having roughly speaking similar military capabalities, which proved to be effective for the Japanese to keep the Mongols at bay for weeks, when they were not outnumbered.

Several Samurai were also able to collect enemy heads, implying that they had the upper hand against multiple enemies when faced into close quarter combat.

All of these sources when analyzed as a whole, describe both factions having roughly speaking similar military capabalities, which proved to be effective for the Japanese to keep the Mongols at bay for weeks, when they were not outnumbered.

The "Kamikaze" - The role of the typhoons in the Mongol Invasion

Among the most common narrative of the Mongolian invasion of Japan, at the first place we could definitely see how the divine wind (kamikaze - 神風) saved Japan twice from a crushing defeat.

However, this is incorrect from so many perspectives to the point that it is hard to decide where to start.

The major issues is that the Japanese army would have not been defeated in the first place mainly due to the fact that the capability of the Mongol-Goryeo armada to project its full military potential in the islands of Japan was very limited.

This is evident when we consider both campaigns, as the Mongols struggled to gain a stronghold in Kyushu, despite gaining few peripherals islands like Tsushima and Iki. The terrain of Japan would have made the entire feat impossible to say the least, not to mention that the Hojo regency didn't actually mobilize its entire force yet (although that is arguable wheter or not they would have been able to muster so many troops).

While in the first invasions the generals themselves realized that they lacked the adeguate resources to subjugate Kyushu, let alone the entire country, in the second one they were forced to stay at sea for months due to the fortifications and the stiff resistance of the Japanese.

The major issues is that the Japanese army would have not been defeated in the first place mainly due to the fact that the capability of the Mongol-Goryeo armada to project its full military potential in the islands of Japan was very limited.

This is evident when we consider both campaigns, as the Mongols struggled to gain a stronghold in Kyushu, despite gaining few peripherals islands like Tsushima and Iki. The terrain of Japan would have made the entire feat impossible to say the least, not to mention that the Hojo regency didn't actually mobilize its entire force yet (although that is arguable wheter or not they would have been able to muster so many troops).

While in the first invasions the generals themselves realized that they lacked the adeguate resources to subjugate Kyushu, let alone the entire country, in the second one they were forced to stay at sea for months due to the fortifications and the stiff resistance of the Japanese.

So one of the key elements of the pop version of these invasions, hence that the storms saved the country of the Rising Sun is simplistic and rather unrealistic, as the entire feat was doomed to fail from the beginning.

Yet the storms were real events, historically, although its importance was overly exagerated over the years by some historical sources themselves.

Vassal of such historical narratives is the Hachiman Gudokun (八幡愚童訓) which deal with several exagerations on how the Japanese troops struggled and succeded thanks to the divine intervention of Hachiman.

Yet, even within this source we do not find credible evidences of a typhoon hitting the Mongol fleet as the invader is described to leave the wind as soon as reverse wind approached the land. Such typhoon is mentioned however in Yuan sources, but if anything, the storm would have hit a defeated armada on its way to Korea, and was not itself the cause of retreat.

On the other hand, we have plenty of evidences both from archaeology as well as written sources of a severe storm hitting the fleet during the second invasion.

Still, said storm would have manifested itself around the 15th of August, while the first raids begun on the 9th of June against Tsushima.

The Yuan-Goryeo fleet was stucked at Hakata and in the nearby islands, unable to make decisive land progress, from the 25th of June.

So it is clear and evident that such crushing defeat would have hardly be real for the Japanese side, as the Mongols were unable to gain anything for several months of conflicts.

Yet, even within this source we do not find credible evidences of a typhoon hitting the Mongol fleet as the invader is described to leave the wind as soon as reverse wind approached the land. Such typhoon is mentioned however in Yuan sources, but if anything, the storm would have hit a defeated armada on its way to Korea, and was not itself the cause of retreat.

On the other hand, we have plenty of evidences both from archaeology as well as written sources of a severe storm hitting the fleet during the second invasion.

Still, said storm would have manifested itself around the 15th of August, while the first raids begun on the 9th of June against Tsushima.

The Yuan-Goryeo fleet was stucked at Hakata and in the nearby islands, unable to make decisive land progress, from the 25th of June.

So it is clear and evident that such crushing defeat would have hardly be real for the Japanese side, as the Mongols were unable to gain anything for several months of conflicts.

As historian T.Conlan commented on the whole episode, the thypoon that hit the fleet, while devastating on its own, was hardly a decisive factor on the defeat of the Yuan forces but more of coupe de grace on a dying enemy.

Sword's struggles - Did the Mongol brought the Japanese sword making to a change? (WIP)

Military "Evolution" or "Revolution"?- What the Mongol invasions brought to Japan (WIP)

Nobody calls the Spanish colonial empire Austrian because of the reigning house: Habsburg or the American revolutionary war, the first colonial victory over the Germans, given the fact that at the time the United Kingdom was governed by Hanover family of German origins. I would rather call mongol invasions of japan by the yuan-goryeo armada...

ReplyDeleteThat's right, I get your point; I did that for sake of semplicity. After all, even the Yuan-Goryeo armada might not be entirely correct as Jurchens and Han Chinese were also recruited into this one. "Mongolian or Mongol" army might be a broader middle ground maybe, anyway I'll either find something better or add some context to clarify my choice of words !

DeleteBy yuan dynasty i already include han Chinese and jurchens.... all part of the same state... goryeo was like a semi-autonomous state within it.. so yeah yuan-goryeo

DeleteGood point; this would also highlight the relationship among Yuan and Goryeo, since Korea while under Yuan control wasn't directly incorporated into its empire like the former Song Dynasty.

DeletePlease, Can you do something like that about Battle of Fukuda Bay?

Delete@Unknown yes definitely! It would be awesome to do some specific research on that, I'll see what I can do in the near future!

DeleteGood to see you find articles again, which by the way did you received any of the ones that I message you? About the numbers what I read is the first Invasion number about 38,000 men, as for it being possible for 100,000 men

ReplyDeleteI know it's been said they did that again in Vietnam and even exceeding it.

I did find this comment on Kings and generals newest video interesting be enough.

">>The First Plan of Invasion of Japan (1274- )

Marshal:忽敦(The former Mongolian warlord)

Mongolian and Han Army: 15,000-25,000

Koryo Army: 5,300-8,000

The total for both armies, including the sailors: 27,000-40,000.

726-900 warships.

>>Second Plan of Invasion of Japan (1279- )

Marshal:忻都(The former Mongolian warlord)

'Eastern Road forces' (Mongolian and Goryeo Army): 40,000-56,989

Jiangnan Army (former Southern Song Army): About 100,000

Gangnam military sailors (number unknown)

The total for both armies: 140,000-156,989.

4,400 warships."

Anyway good luck on the rest of your work.

Hi!

DeleteI've double checked the e-mail and I missed your messages, unfortunately I have saw them now but I'm gonna reply for sure!

About the numbers of the invasion; that paragraph is still not completed, I'm aware of those other estimations but I also know that those are highly discussed because the burden of supporting such an army (especially the second one) at sea for that long is definitely a massive and colossal feat. The Mongols might have been able to do that, but the following defeat should have undermined their military and economical power to a very larger extent due to the loss of so many men and resources.

Awesome post! Also quite timely. XD

ReplyDeleteCan'y wait for you to finish this one!

To be fair, I do not think the second invasion being the largest amphibious military deployment prior to WW2 is so far fetched. It should be noted that the Mongols had unprecedented amounts of resources and the largest civilisation in the world at that time, and the attack on Japan was a very impotant undertaking for Kublai Khan. I don't see any other civilisation having the manpower or reason to launch an attack of such magnotude prior to WW2

Thanks!

DeleteYou are right, but the main issue is that those numbers are still massive for such a sea operation with 13th century technology. The biggest problem would have been the burden of such feat after the following defeat. The loss of that many men and resources should have undermined the political egemony of the Yuan much more than what actually happened for the "aftermath" so it is reasonable to question those numebers.

On the other hand I haven't finished the pharagraph yet so I will still mention the other side of the estimation for sure :)

A map showing the locations Mongol landing, moving, and where the battles took place, would be very appreciated.

ReplyDeleteThat would be a good idea indeed!

DeleteI'm planning to discuss both invasions in such way in other articles of this series :)

There is also a problem of Japan being an archipelago. Naval invasions have always been a complete pain in the ass, especially in pre-modern time, with insanely high possibility of failure. That's also why Britain was rarely plundered or occupied by foreign troops in comparison to other countries.

ReplyDeleteAnd as of numbers, ancient and even relatively modern chronicles always need to be double checked. Even 17th century European accounts sometimes give insane army numbers, so nothing surprising here.

Indeed, such numbers would have been a very high risk operation given the distance needed. Therefore I have to say I prefer the low end numbers as they seems more reliable and realistic as well

DeleteFrom China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368, the author wrote that the Yuan Mongol/Chinese/Jurchen soldiers was mostly composed of conscripts, criminals/prisoners and former rebels/enemy soldiers. The Goryeo army seems to be the professional part in that army.

ReplyDeleteThe information was taken from the Yuan Shi and rewritten by the author.

"Since the men were mostly former enemies, deserters, and pirates,

their loyalty and their trustworthiness were in doubt, so to keep watch over

them three thousand Mongols of the Shangdu garrison were assigned to the

Southern Force."

"The khan also instructed Hong Dagu to mobilize the

additional Yuan forces and he was authorized to make up any shortages in

men by conscripting criminals in prisons."

The Yuan probably did not want to risk their soldiers in a sea invasion as they might not had the skill themselves.

Their equipment was also lacking.

"The response of the Yuan court was rather niggardly. Instead of five thousand

bows it sent one thousand and instead of five thousand suits of armor, it sent

only one hundred."

It seems that both sides did not had their best in the invasion. The Yuan-Goryeo army did not had their best soldiers, while the Japanese might not draft all their available manpower.

Interestingly, the Mongol Invasion of the Sakhalin Island probably inflicted greater damage against the Japanese than their previous 2 invasions, as it drove the Ainu against the northern Japanese provinces.

I couldn't agree more with what you wrote; indeed the Mongol Invasion saw the Yuan forces to underperform under many strategical and tactical point of views (from a overall bad fighting performance that wasn't enough to defeat Japanese defenders in Kyushu to the wrong type of ships chosen) and on the other hand it didn't saw the full power of the Shogunate although such full scale mobilization would have been a massive feat for teh Hojo regency in Kamakura, that might have lacked the power to force the entire nation at war.

DeleteThe Yuan shi has been criticized tho.

Deletehttps://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Yuan

which claims they were faced by 102,000 Japanese warriors in the first invasion I believe,

It was something created in the late ming dynasty.

On a kind of belated note I did find this about how the Mongols got Conquest people to fight for them.

http://mongoliafaq.com/2019/10/28/why-did-the-conquered-people-fight-for-the-mongols/

@Gunsen

DeleteYes, the book also said that the Yuan sent naval experts to teach Mongol commanders only after the failed second invasion in preparation for the third invasion.

About the mobilization capability of Japan, how capable was Japan in mobilizing large armies before the Sengoku Period?

In the Sengoku Period and afterward, armies seems to be large at least compared to contemporary Western ones.

The Nanbokucho Period also had large armies, probably because of the emperor manage to push the shogun as a ruling power.

Also how easy could be someone be a Samurai?

I heard that before Hideyoshi, anyone could be a Samurai even peasants, and that Hideyoshi restrict this practice and made the Samurai into a separate and hereditary class.

@Eagle 1 Yes indeed that's a major problem with the Yuan Shi, it is not exactly period source and it might be biased toward the newly established Ming dynasty.

DeleteIt is also similar for the Goryeosa, which was written after the end of the Goryeo period in Korea; both sources deal with the Mongol invasion but to be fair, the main one to consider should be the Mongol Invasion Scroll of Suneaga as he was present and was written shortly after the battle.

@Joshua

It's hard to tell because most of the time the warfare was localized hence it didn't required a major burden of troops up until the late 14th and 15th century in which we could find period of endemic warfare.

I can't say with precision but keep in mind that usually the numbers for various armies in the chronicles are still very unreliable, like in the Taiheiki for example.

If the Yuan would have managed to establish a stronghold in Kyushu we would have seen a larger mobilization, but I would say that it would have been hard for the Hojo regency to pull more than 50 000 men at once.

As for your last question, it's complicated. Being a Samurai meant being a retainer so essentially anyone serving into army could made a military carrer like Hideyoshi, starting as weapon carrier.

Hideyoshi restricted such social mobility indeed. However, before that time period, military carrer wasn't as widespread due to the lack of Sengoku period warfare and endemic war. I actually need to look into myself because honestly I don't know much about the social status and apparatus of Kamakura and Heian period!

That is what bother me about the term Samurai.

DeleteCould the footmen depicted in Kamakura-Nanbokucho period be called Samurai like the one riding on horse? Could they be called Ashigaru?

Did the term Samurai combine the definition of knight and man-at-arm?

Could the soldiers of the Ritsuryo system and early Heian period be called Samurai?

On a different topic, would it be out of topic, if I request an article on possible Samurai body height and strength?

In an article on the resurgence in wheeled vehicles after the Edo period ban, a European writer said that the Japanese carried weights that he couldn't even began to lift and they carried such things for miles.

He also said that boys in early 20th century Japan usually carried 180 pounds of eggs to sell. The boys would carry 100 pounds on his back and 40 pounds on each arm.

That weight would be more than the combat load of US marines in 2007.

https://us.myprotein.com/thezone/training/military-mass/

According to “a 2007 study by a Navy research-advisory committee,” it was determined that “Marines typically have loads from 97 to 135 pounds.”"

That would be around the carrying capability of a Neanderthal.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/could-a-modern-human-beat-a-neanderthal-in-a-fight-93909531/

It could be an exaggeration, but I think it is not impossible for a people to develop such strengths considering that they did not had any other alternatives for carrying goods.

I do feel you here when it comes to the word "Samurai".

DeleteThe term as we know it today (members of the elite warrior class in Japan) is indeed a byproduct of Edo period laws and customes.

The word itself had different meanings and wasn't used that much before the Edo jidai, so you have tons of words to indicate mounted warriors belonging to the elite warrior class.

For the Heian period, we usually called them Buke - 武家 or Mononofu written as Bushi - 武士. During the Kamakura period the proper term would be Gokenin - 御家人 and then you have plenty of words associated with horses like Kibamusha - 騎馬武者 or simply 騎 Kiba for the Sengoku period.

What really made you a Samurai in this period was the fact that you owned land and could own a horse plus the activity into a military campaign which would lead to martial arts and tactic studies.

During the Sengoku period, there was a lot of social mobility but before that you couldn't gain land as the state of war in Japan didn't allow it as much as in the mid 16th century.

Foot soldiers were called Ashigaru after the 14th century, when the term was invented, but before that you had heishi - 兵士 and unlike the Ashigaru, these were the foot retainers of the Samurai of their age, so they were related to the retainer family with some type of bond while Ashigaru were essentially mercenaries more or less.

About your request, I have to think about it; it's definitely more related to antropology and there are already few academic papers that talk about height in medieval Japan. As far as strength is concerned, keep in mind that our ancestors were much more fit than us due to their daily manual labor even if they had bad nutrion so it's not that surprising altough those sources might be exagerating a bit

I'm not sure about that I came across comments that mention " he was not consider a samurai unlike when most westerners think"

DeleteOr "he did not became Samurai until he married into a family of one."

But I haven't been able to check it out myself.

I did find this though.

https://www.samurai-archives.com/code.html

"Toyotomi Hideyoshi (not a daimyo himself as we consider the term)."

@Gunsen

DeleteThank you, the info on Samurai and the other terms is very interesting.

I suppose that the mobilization and recruiting method of warriors in Japan change in different periods.

Why did the Japanese had the idea to create the Ashigaru? And what happen to the Heishi after the 14th century?

@Eagle 1

I just heard it from a random comment in a forum. It seems that the definition of a Samurai did change over time.

Weren’t people from medieval Japan really short? I remember reading that the medium height for men was 1,55m. Kinda strange that they used weapons basically the same size and weight of European ones.

DeleteYes indeed the definition of the term changed a lot. It also doesn't help that sometime, the true meaning of the word is lost through translation for example.

DeleteAnyway, the Ashigaru were assimilated into Japanese army during the war of the 14th century since the reform of the Muromachi period allow warlords to grow more influence and acquire more wealth, hence they could sustain such levies troops and train them to fend off the horse archers. The Heishi didn't disappeared, they were simply the direct retainers on foot of those Samurai.

@O

There are numerous studies about the height of Japanese men during the ages. They weren't exactly 1.55, more like 1.60-62m tall and still that's an average figure. if you consdier that wealthier Samurai existed as well, whom had access to better nutrition and so on.

@Gunsen

DeleteI don’t think that wealthier samurai were much taller either. Famous Daimyos like Takeda Shingen,Date Masamune and Tokugawa ieyasu were still basically 1,6m. ( sorry for bothering you and for my bad English)

@Gunsen

Delete@O

Some Japanese seems to be as tall as Westerner here.

https://livedoor.blogimg.jp/nwknews/imgs/b/5/b5e25a2b.jpg

Here, there is a Samurai that is likely taller than the standing European.

https://i.pinimg.com/474x/08/bb/61/08bb61156072c399c207e57522d0fcf2--meiji-restoration-katana.jpg

@O

DeleteThis is true but there are also Samurai and Daimyo like Oda Nobunaga and Maeda Toshiee which were 1.70 and 1.80 meters as far as I know.

Same thing for Saigo Takamori

I'm a bit late for this but this is awesome!!

ReplyDeleteI really hate when people says that the "samurai didn't used propper tactics because they were dueling each other" wich is a nonses having in consideration many battles of, for example, the Genpei Wars

Don't worry you are not late: actually everyone is "early" as the article is not finished yet :'D

DeleteIndeed, we do need to reckon that the military status of ""feudal"" armies wasn't great compared to modern or antiquity (like the Roman army) but at the same time the romantic view of honorable duels is such a non-sense that I wonder why so many people still accept it as it is.

War is a collective effort and people wanted to live nonetheless, so that's why some form of tactic was elaborated even when armies weren't as professional as the later ones

I suppouse that people belive that myth beacuse fits with the romantic narrative of the honorable warrior and this bullshido thing that hollywood originated.

DeleteThis remember an article of another blog about the Mongol invasions wich in a paragraph says that the "japanese army impresed the invaders because they were highly disciplined and coordinated" and in the next paragraph talks about how the samurais challenged single oponents to duels, wich basically contradicts the first paragraph.

Is like the Cagayan bullshit, is simply nonsense and, for some reason, many people never thinked that it has no fucking sense

I think I should point out that Mongols continued fighting and won the battle even after Liu Fu Heng was wounded.

ReplyDeleteAre you sure about that? I remember that the wound of Heng was crucial for the retreat of the army. But I'll double check this anyway!

DeleteYes. Liu Fu Heng was wounded when Yuan Army was attacking Hataka Bay during late evening. They returned to their ship from Hataka in the night, by that time Japanese army already retreated to Dazaifu.

DeleteFrom my understanding, Yuan Army initially landed at Imazu and slogged/rode pass Akasaka, Torikai-Gata and Momoji-baru (notable sites of Japanese victory, which didn't seem to slow the Yuan army) along the way, finally arriving at Hataka in the evening. The fleet followed land army along the coast and continuously sending troops to the land (additional troops landed at Meinohama, Momojibaru and Hataka itself as the fleet gradually moved eastward).

By nightfall, both Yuan fleet and Yuan army were at Hataka Bay, thus the army was able to embark their ships immediately (rather than having to walk back to Imazu).

Of all people to write about this topic, you are definitely the first that would come to my mind as being capable of doing a great job, and you sure did deliver what I expected, despite this being such a debated and myth-filled topic, even amongst the Japanese community. Keep up the good work in these troubling times, you're the type of person who makes it possible for us history nerds to keep going!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for the support! I hope to finish this as soon as possible!!

DeleteHey, I know this out of nowhere but if you don't mind can you sign this petition to get rid of a group name MAP as well as Zoophilia on Twitter and shared it if you can to help get rid of those sickos

ReplyDeletehttps://www.change.org/p/twitter-inc-force-twitter-to-stop-ignoring-pedophilia-and-zoophilia?recruiter=597510221&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=psf_combo_share_abi&utm_term=share_petition&recruited_by_id=4c0471c0-7b3d-11e6-afd9-b9e8fd010c0b

Read the details.

Thanks I'll have a read!

Deleteis the "honor duels" thing something repeated in Japanese takes on the Yuan invasion?

ReplyDeleteI saw "tachi chipped against leather armor" about a decade ago on a history forum, I think this is the cited Japanese source: https://web.archive.org/web/20191013040019/https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/9768/

On the chipped blades... there were already stoutly built naginata and other polearms expected to smash against steel armor, so if tachi were chipped faster against yuan armor then it wasn't due to a lack of technology but preference for sidearms vs main arms.

DeleteThe honor duels is a exagerated version of the fights that could be find in some Japanese sources like the Hachiman Gudokun which was written later by monks who didn't partecipate into the fights, so it shouldn't be take into consideration definitely.

DeleteThe chipped blades is something I was about to write here; there are no actual historical sources that mentions said consistent failure against Yuan armor of the Japanese swords, but it is found in the first modern work of the invasion (which iirc is about 100 years old) and so everyone cited that, without knowing that is more or less a groundless statement.

Moreover, if you read the chronicles of the same century, we can read of swords literally called "double helmet splitters", so with that reputation in Japanese chronicles, I find it hard to believe that those blades chipped rather easily against leather and textile armor.

Any chance you will implement something like the great Ming blog where you can see the newest post on articles so one does not have to goo through every single post to see if there has been anything new?

ReplyDeleteBy the way on the begining of Zenkunen Emakimono Complete 前九年絵巻物 you can see at the lower part near the edge a kabuto with what looks like a mail shikoro.

Delete@Tobi unfortunately at the moment I'm extremely busy and I can't manage to use my time properly, hence why there is no posting.

DeleteHowever I'll try to work on it as soon as I'll return to a normal schedule of posting!

Also you are right, mail shikoro show up as well in the famous Heike Monogatari Emaki although it looks to be a plate and mail combination.

Amphibious invasions are always a pain in the ass. Even in the modern era. In ancient times it was suicidal. Which is why island nations are seldom invaded.

ReplyDeleteMaybe this may be a bit-Actually no, it's completely off topic, but if you don't mind me asking you a question on pre-Samurai history in general, was there a hereditary warrior class before the rise of the Bushi in Japan? I read something about the 武官 somewhere, but I couldn't find a lot of information and I'm not sure if they fit the description. If not, was military authority left in a more feudal way to regional nobles and aristocrats?

ReplyDeleteIt is a bit complicated as Pre-Samurai history means a big span of time. In general, low rank nobles did train into martial arts and given their status were the only one that could reliably afford horse and weapons, so I would say yes.

DeleteIf it can help, iirc there are detailed paragraphs on pre-samurai state of feudal warriors, particularly in the Ritsuryo system in Friday's books "Samurai, Warfare and the State".

Thank you for the reply! I'll read into this book as you suggest, especially since the Ritsuryo system was always a topic I had trouble understanding beyond superficial level.

DeleteYou're welcome! To be fair it's a fairly overlooked period in Japanese history, unfortunately. But very interesting nonetheless

DeleteAs always a great article.

ReplyDeleteYou got mentioned in Youtube video with already 27000 viewers I hope you will be flooded with new readers!

ReplyDeleteThat would be awesome indeed!

DeleteYari article 2023? XD

ReplyDeleteMaybe :'D ! I think I should make a blog post to update everyone but currently I'm working on a project for developing a historically accurate mod for bannerlord, and it's very fun and I can put to work all of this knowledge to something concrete - which was the aim of my articles nonetheless.

DeleteHowever I haven't been able to dedicate much time on the blog, sadly

So we get a Sengoku mod for bannerlord?

ReplyDeleteIt's on the making and I'm part of it ;)

DeleteHold on, really!? Damn, my hopes for this mod (which I'm assuming is Shokuhō) has just skyrocketed! I can't wait to see how it'll turn out, especially if you're working on it!

DeleteIndeed I should make a post on that with some preview! That's the main reason why I'm not writing much anymore so I think it's deserved :D

DeleteAn interesting, promising article. From what I've read so far it seems like that the situation were hordes of ruthless pragmatic mongols tear stupidly-honor-bounded samurai to pieces like in Ghost of Tsushima is , to be blunt, crap.

ReplyDeleteThere's a point I'd like to make regarding the following statement from TVTropes:

The Yari became popular because of the Mongol invasion of Japan; in the brief clashes, the Mongols and their Korean conscripts advanced in tight formation. The Japanese learned the lesson.

I would like to know if there's an amount of truth on this or, if not, if I can correct the statement and quote your eventual sources to justify my edit, in case someone protests.

Again, thank you very much!

There is a good piece written by the fellow ParralellPain on reddit that address the whole claim of "Samurai 1 on 1 duel" typical of the early period gunkimono. Long story short, it doesn't make sense: no one is going to hear you in the first place when horses are running, armors and weapons are moving and people are dying around you!

Deletehttps://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/9g56y0/did_feudal_japanese_samurai_actually_pair_off/

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/gtnsi0/is_it_true_that_samurai_found_difficulty_fighting/

Also, the Mongol invasion really didn't change tactics, equipments or warfare trends in Japan, although it is true that those changes happened in the following 14th century.

We can go into a detailed dicussions why that wasn't the case, but the short answer is that the Mongol invasion kickstarted the fall of the Kamakura Shogunata and the Hojo regency, which lead to the Nanboku-chō period wars, a period of warfare that affected all the country for several years, which also saw the introduction of "ashigaru" infantry soldiers, fortifications and sieges.

It's rather easy to see that a short lived conflict that lasted few months (both Mongol invasions combined), localized in a small are of Kyushu and smaller islands cannot influence the national situation as much as the longer, more comprhensive and dynamic conflicts of the 14th century.

That's what lead to the widespread usage of yari (as well as the rising role of infantry and fortifications) which to be fair started to have a larger impact from the 15th century Onin war and after.

So I can pretty much edit that one ? Good.

DeleteThank you again!

We need to separate the first invasion from the second invasion, as there were some substantial differences. Furthermore, for the second invasion, we need to separate the smaller fleet from Korea with the larger fleet from southern China. The Mongol fleet from Korea had engaged in battle with the Japanese for several weeks and couldn't make much progress, and retreated to link up with the larger fleet sailing from China. The larger fleet that sailed from China didn't even engage in battle before it was sunk by the typhoon.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting, will you continue with the blog?

ReplyDeleteUn artículo muy interesante sobre las guerras antiguas en el lejano oriente.

ReplyDeleteHey @Gunsen I don’t know if you are still interested in continuing this blog but if you are then what do think about doing topics like the various Japanese matchlocks/their evolution or maybe the practice of kabutowari. I’d like to know your thoughts

ReplyDelete>>"There are plenty of accounts of low ranking retainers back stabbing other Samurai in order to save their lords or Samurai being killed by unsigned arrows, which were shot by low ranking retainers, as Samurai usually had their names written on theirs."

ReplyDeleteThis would be a great next article. A timeline of "dishonorable-by-hollywood-standards" side switching, ambushes in the long history of samurai warfare.