Shudo (手弩) and Ōyumi (大弓) - Japanese Crossbows

Shudo (手弩) and Ōyumi (大弓) - Japanese Crossbows

Ono no Harukaze using a crossbow, from 前賢故実.

In this article I would like to address one of the most mysterious and interesting aspect of Japanese military history: Crossbow's usage.

In fact, people usually (and for a very good number of reasons which I will explain in this article) don't associate Japan with crossbows at all.

However, not only the Japanese knew crossbows, they also occasionally used them in warfare.

First, it is fair to point out that unlike other unknown elements of ancient and feudal Japanese warfare, like shields, axes or maces which are usually not associated neither with Japan or the Samurai, the crossbow never saw much use at all.

If those aforementioned weapons were rare, the crossbow was even more rare; but it is still worth talk about it.

Shudo (手弩) - Hand held crossbow

Shudo is the Japanese name for hand held crossbows, but it is not the only one. It was also know as ishiyumi ( written either 弩 or 石弓), shudo (手弩), doshu (弩手) or dokyū (弩弓).

Shudo is the Japanese name for hand held crossbows, but it is not the only one. It was also know as ishiyumi ( written either 弩 or 石弓), shudo (手弩), doshu (弩手) or dokyū (弩弓).

The first type of crossbow found in Japan was excavated in Shimane prefecture and dates back to the Yayoi period (probably around the 200-300 A.D). Like anything dealing with Yayoi, not much is known and that is the only example excavated.

It was a rather simple model, made of wood.

There are other references for this kind of weapon; the first is inside a report concerning a bandit raid on the Dewa provincial office in 878, in which “100 shudo" were stolen. The second, an inventory from the Kōzuke provincial office compiled around 1030, lists “25 shudo” (apparently its entire stock) as missing.

According to design and the manufacture of the only trigger mechanism excavated in Japan, which was made of bronze, these crossbows were imported from China or Korea.

We do not know how they looked like nor how powerful they were, unfortunately.

It is possible that crossbows saw relative use in between the 9th and 10th century, but the few scattered evidences disappeared completely from Japan after this period, up until the Edo jidai.

A sketch of a shudo from 請求記号, Edo period.

There are few examples of crossbows from the Tokugawa age; some are inside private collections, others are preserved in the Royal Armories museum in Leeds and at the MET.

These late shudo are made with whale bones and they are built in two layers like leaf-spring.

The one at the Met, at least from its description, was made with horn, steel and wood.It is very possible that these crossbows were either based on Chinese models, or directly imported.

The ones in the R.A. museum has still its own bolts, which are fitted with armor piercing heads.

According to design and the manufacture of the only trigger mechanism excavated in Japan, which was made of bronze, these crossbows were imported from China or Korea.

We do not know how they looked like nor how powerful they were, unfortunately.

It is possible that crossbows saw relative use in between the 9th and 10th century, but the few scattered evidences disappeared completely from Japan after this period, up until the Edo jidai.

A sketch of a shudo from 請求記号, Edo period.

There are few examples of crossbows from the Tokugawa age; some are inside private collections, others are preserved in the Royal Armories museum in Leeds and at the MET.

These late shudo are made with whale bones and they are built in two layers like leaf-spring.

The one at the Met, at least from its description, was made with horn, steel and wood.It is very possible that these crossbows were either based on Chinese models, or directly imported.

The ones in the R.A. museum has still its own bolts, which are fitted with armor piercing heads.

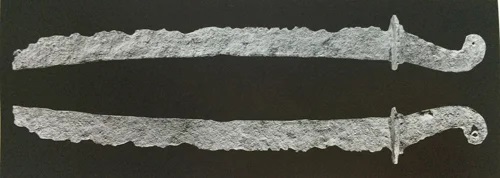

A Japanese crossbow's bolt from the Met museum.

Although these weapons look functional, it is impossible to establish the power or if they were made to work as weapons and not as toys for the bored Samurai of the Edo period. Just like with their 9th and 10th centuries counterparts, we do not know much about them.

Another hand held crossbow worth mentioning is the steel crossbow ordered by Matsudaira Sadanobu in the early 19th century. It was made in 1820, and the design is quite impressive considering the fact that Japan stayed with Sengoku period technology up until the mid 19th century.

The bow was made of spring tempered steel, and the trigger mechanism itself had a spring made of steel.

As I have already explained in my article about bow, the Japanese were already familiar with steel bows (and thus spring tempering) at least since the 16th century, although they were rare due to the cost and practical issues of producing and using a bow of steel.

Another hand held crossbow worth mentioning is the steel crossbow ordered by Matsudaira Sadanobu in the early 19th century. It was made in 1820, and the design is quite impressive considering the fact that Japan stayed with Sengoku period technology up until the mid 19th century.

The bow was made of spring tempered steel, and the trigger mechanism itself had a spring made of steel.

As I have already explained in my article about bow, the Japanese were already familiar with steel bows (and thus spring tempering) at least since the 16th century, although they were rare due to the cost and practical issues of producing and using a bow of steel.

The second part of the crossbow, with the stock and other components.

The entire weapon drawn

So, why were these weapons not considered that much in Japan, especially during the Samurai warfare age? It may look odd, considering the distance from China, a country that made crossbows one of their military symbols for much of their history.

There are a good number of reasons which explain the situation quite well.

The first reason has to do with native production issues. To make an efficient crossbow capable of piercing armor, you need either spring tempered steel or a composite structure made of horn, bones, sinews and wood, which was the way early crossbows were made pretty much everywhere.

The problem with tempering steel is that the technology required to make a homogeneous piece of steel and then properly hardening and tempering it wasn't available prior to the 10th (century and even later), not to mention the cost of such products.

On the other hand, as I have explained in my article about Japanese bows, Japan lacked any serious supply of bones, horns and sinews.

This wasn't a major problem with bow construction, since you could still make a very powerful bow with wood and bamboo; it only need to be very long, hence the dimension of the Yumi.

However, this is a major drawback with crossbows design; manufacturing crossbows with composite bow staves of wood and bamboo comparable in length to those of regular bows would have resulted in a weapon too unwieldy to be practical: not merely extraordinarily wide – and not readily usable by troops standing in close ranks – but also extraordinarily long, as it would have been necessary to lengthen the stock to permit a sufficient draw.

This however wasn't the only problem. In fact, importing Chinese models would have solved the issue, and as far as we know the few crossbows used prior to the 10th century were indeed imported from China.

There was a true indifference to this weapon in Japan, mainly due to its tactical limitations.

While crossbows are extremely effective weapons, they have some detrimental flaws that made them unsuitable for the Japanese warfare of the period.

Crossbows cannot be reloaded while riding a horse, or while walking, they need drilling and serious training to be operated properly, they are cumbersome to carry around and their "rate of fire" is very slow compared to that of bows.

The military structure and organization of the early Samurai didn't allow these weapons to prosper, because of the lack of discipline among infantry soldiers, the prevalence of mounted warriors as well as the very mountainous and uneven terrain of Japan. All these aspects combined made hand held crossbows a bad choice for the typical Japanese medieval warrior, and soon the bow prevailed up until the mid 16th century.

There are a good number of reasons which explain the situation quite well.

The first reason has to do with native production issues. To make an efficient crossbow capable of piercing armor, you need either spring tempered steel or a composite structure made of horn, bones, sinews and wood, which was the way early crossbows were made pretty much everywhere.

The problem with tempering steel is that the technology required to make a homogeneous piece of steel and then properly hardening and tempering it wasn't available prior to the 10th (century and even later), not to mention the cost of such products.

On the other hand, as I have explained in my article about Japanese bows, Japan lacked any serious supply of bones, horns and sinews.

This wasn't a major problem with bow construction, since you could still make a very powerful bow with wood and bamboo; it only need to be very long, hence the dimension of the Yumi.

However, this is a major drawback with crossbows design; manufacturing crossbows with composite bow staves of wood and bamboo comparable in length to those of regular bows would have resulted in a weapon too unwieldy to be practical: not merely extraordinarily wide – and not readily usable by troops standing in close ranks – but also extraordinarily long, as it would have been necessary to lengthen the stock to permit a sufficient draw.

This however wasn't the only problem. In fact, importing Chinese models would have solved the issue, and as far as we know the few crossbows used prior to the 10th century were indeed imported from China.

There was a true indifference to this weapon in Japan, mainly due to its tactical limitations.

While crossbows are extremely effective weapons, they have some detrimental flaws that made them unsuitable for the Japanese warfare of the period.

Crossbows cannot be reloaded while riding a horse, or while walking, they need drilling and serious training to be operated properly, they are cumbersome to carry around and their "rate of fire" is very slow compared to that of bows.

The military structure and organization of the early Samurai didn't allow these weapons to prosper, because of the lack of discipline among infantry soldiers, the prevalence of mounted warriors as well as the very mountainous and uneven terrain of Japan. All these aspects combined made hand held crossbows a bad choice for the typical Japanese medieval warrior, and soon the bow prevailed up until the mid 16th century.

Ōyumi (大弓) - Siege crossbow

While hand held crossbows saw limited use throughout the entire military history of Japan, the same cannot be said about siege crossbows, called Ōyumi. This weapon is a little bit more famous and there are more sources that deal with it.However, just like the other crossbows, we do not know how it looked like nor how it was supposed to work. Descriptions or drawings have never been found.

A possible artistic representation of the Ōyumi.

This artillery weapon was brought to Japan by Koreans in 618 and the Japanese started to deploying it regularly by the 670s against the Emishi.

Despite this limit and the slow decline, siege crossbows were still used up until the late 12th century.

In the Mutsu Waki, describing the war of the 1053 to the 1062, the use of both arrows and stones is recorded.

The usage of the ōyumi is also recorded in the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba dealing with the war of the late 11th century and the last recorded use is dated to the 12th century, during the Gempei war.

The skill required to use and make such weapon declined through the ages, so it is not a surprise to see this weapon disappearing completely after the 12th century, when a long period of peace was established and the knowledge behind the ōyumi was lost forever.

I Hope that you liked the article, for any question, don't hesitate to write a comment! I'll be glad to answer.

Feel free to share the article and spread the word! Thank you so much for your time.

While hand held crossbows saw limited use throughout the entire military history of Japan, the same cannot be said about siege crossbows, called Ōyumi. This weapon is a little bit more famous and there are more sources that deal with it.However, just like the other crossbows, we do not know how it looked like nor how it was supposed to work. Descriptions or drawings have never been found.

It appears to have been some sort of platform-mounted, crossbow-style catapult, on the order of the Greek oxybeles or lithobolos, the Roman ballista, and similar devices, perhaps capable of launching volleys of arrows or stones in a single shooting, possibly a variation of the Chinese repeating crossbow.

A possible artistic representation of the Ōyumi.

This artillery weapon was brought to Japan by Koreans in 618 and the Japanese started to deploying it regularly by the 670s against the Emishi.

A chronicle entry from 835 notes the existence of a “new ōyumi” (shindo), invented by

Shimagi Fubito Makoto, that was supposed to have been able to rotate freely, shoot in all directions, and be easier to discharge than the existing design. The text remarks that, when the weapon was demonstrated, the assembled courtiers could “hear the sound of it being set off, but could not see even the shadows of the arrows as they passed."

Siege crossbows were placed on several key locations on the Sea of Japan to prevent a Silla pirates raids during the 9th century.

One critical limit of this weapon was the skill required to use it. Several sources underlined how hard it was to operate it and that troops needed to be trained to use it.

Siege crossbows were placed on several key locations on the Sea of Japan to prevent a Silla pirates raids during the 9th century.

One critical limit of this weapon was the skill required to use it. Several sources underlined how hard it was to operate it and that troops needed to be trained to use it.

Between 814 and 901, the court received requests for ōyumi instructors from no fewer than seventeen provinces. All had the same complaint: regrettably, the weapons in their armories were going to waste because no one knew how to use them.

Despite this limit and the slow decline, siege crossbows were still used up until the late 12th century.

In the Mutsu Waki, describing the war of the 1053 to the 1062, the use of both arrows and stones is recorded.

The usage of the ōyumi is also recorded in the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba dealing with the war of the late 11th century and the last recorded use is dated to the 12th century, during the Gempei war.

The skill required to use and make such weapon declined through the ages, so it is not a surprise to see this weapon disappearing completely after the 12th century, when a long period of peace was established and the knowledge behind the ōyumi was lost forever.

I Hope that you liked the article, for any question, don't hesitate to write a comment! I'll be glad to answer.

Feel free to share the article and spread the word! Thank you so much for your time.

Gunbai

Altough you are right regarding the long usage of crossbow in china, it's important to note that by the ming dynasty , crossbow was rarely used in battle, and most generally by south china ethnic minorities ,that at little to no contact possibilities with japan in the first place. Also , you pointed out that a large crossbow of wood would be unwieldy,it was in fact used a lot in by ethnic group such as Lisu ,Yi and of course, the three man Miao crossbow that was especially large.

ReplyDeleteIn the restaurationof the 征倭紀功図屏, you can actally see on the bottom left some yi warrior using large crossbow to fire on the japanese fortification. http://pds9.egloos.com/pds/200808/06/57/f0006957_489972ecf3089.jpg

Thank you for leaving a comment!

DeleteYou are right about the usage of crossbow in China, although when the strongest relationships between the two nations were established, so prior to the Tang Dynasty, crossbows played a vital role in the Chinese military. It was probably due to the Japanese reforms aimed at creating an Imperial system similar to that of Tang China that made the crossbows being imported to Japan, in my opinion.

I see your point on big crossbows being used, however said weapon is useful only in siege like situation since it is more akin to a siege weapon than a regular ranged one (like a bow). In fact, the Oyumi has been used quite a lot, despite being a siege weapon; but the idea of having the whole army issued with such big weapons to use on field battles was impractical, that's what I was saying.

Also, thank you four your references!

It's me again =3

DeleteIt should be noted that crossbow wasn't as important for Tang military as compared to say, Song Dynasty. For the most part, Tang military had a very powerful cavalry force, so it didn't had to rely on crossbow too much. Only about 30~40% of Tang infantry were archers (regular bowmen also outnumbered crossbowmen), and they cross-trained for close combat anyway. For comparison, ratio of crossbowmen in a Song army could be as high as 60~80%.

Secondly, it is possible to reload crossbow on horseback, or retreat to somewhere safe to dismount + reload at least. By Ming period at least, most ethnic minority crossbowmen were actually mountain dwellers or living in places with trecherous terrain (like Ghost Hero said).

Ah, that Edo period Shudo sketch was probably copied from Jue Zhang Xin Fa (《蹶張心法》)

DeleteI'm glad that you left a comment ;)

DeleteThank you for the input! I didn't know about the numbers of crossbowmen actually nor that they were deployed more by Song. I have to say that I used Karl Friday analysis for most of this article in order to add some academic sources, but I admit that I should have spent a little more time.

I'll rewrite that part of the horseback and the reloading as soon as possible (cannot reload is a wrong verb).

Thank you again!

Also it is possible that said crossbow was copied. It won't be the first case; there are two crossbows drawn in another manual and I'm pretty sure to have seen those designs in one of your articles, from a Chinese book.

Ah, I just mean that specific page (not Japanese crossbow as a whole) is possibly copied from a Chinese book.

Delete"Siege crossbows were placed on several key locations on the Sea of Japan to prevent a foreign invasion during the 9th century."

ReplyDeleteNot 7th century? May i ask what is the source used?

From what i know, with Tang beating goguryeo and baekje restoration war in the 7th century AD. In 660, following the fall of its ally Baekje, the Japanese Emperor Tenji utilized skilled technicians to construct fortresses in kyushu and seto inland sea to protect Japan's coastline from invasion.

That's a legit question, I have used mainly Karl Friday "Samurai, warfare and the state in early medieval Japan" as main source to make this article but maybe I miss something here and there; I would double chek it.

DeleteAnyway we know that Oyumi started to be a thing applied to Japanese warfare only in the late 7th century, but you might be right maybe 9th century is a bit too late as the fear of Tang invasion didn't last that long.

Anyway I'll double check it to see if I could find reliable sources to back it up!

I find weird the part "foreign invasion" since it sounds like a large scale foreign-led army crossing the waves. The only foreign threat in the 9th century i believe could have happened and did happen, silla pirate raids

Deletehttps://www.ancient.eu/article/982/ancient-korean--japanese-relations/

"This was despite the fact that Silla pirates continued to harass Japanese coastal traders throughout the 9th century CE."

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=PVrGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA93&lpg=PA93&dq=silla+pirates+japan&source=bl&ots=VDznS2oM0u&sig=ACfU3U2HMdILJL4VjeTx0Q2RYeJc9oHwPQ&hl=pt-BR&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiqk5iYzPXoAhU1E7kGHVI1D_MQ6AEwDHoECAUQAQ#v=onepage&q=silla-pirates-japan&f=false

"Because of unrest during this time, Silla pirates flourished, and piracy on the Japanese coast-particularly in northern Kyushu-increased dramatically, which consequently led to intense Japanese animosity toward Silla pirates. This negative perception was further exacerbated by a series of events, including a Silla immigrant uprising in 820 and its attempt to attack Tsushima. At this point Japan halted all formal relations with Silla. A series of epidemics that broke out following contact with Silla merchants was another major factor leading to the cessation of diplomatic relations and to the negative perception of Silla. Japan further blamed Silla for various calamities: natural disasters such as carthquakes came to be linked with Silla piracy, and the Silla pirates were even blamed for volcanic activity in Japan. In this way, foreign threats were placed in the same class of phenomena as natural calamities, and both were viewed as being dangerous eruptions of chaos."

Furthermore:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toi_invasion

"the Japanese officers suspected them because there had been Korean pirates attacking Japan coasts during the Silla period"

Very interesting to see those relationships between the Silla state and the Yamato one! I haven't had the opportunity to deal with this topic yet but it seems reasonable to defend those coastlines in case of piracy.

DeleteAnyway, it's true that invasion might not be a proper term with nowadays context, but keep in mind that back then pirate raids were often called "invasion" by time period sources. One key example as you mentioned itself is the Toi invasion; despite it being recorded as a very massive fleet of pirates it wasn't a true invasion in the sense of an organized army with a goal but rather a massive raid.

A Tang invasion would have been like the Mongol invasion, that's what I thought. Regards

Deletedo you think ninja's. like real ninja's not movie ones would have used these before the advent of gunpowder.

ReplyDeleteGreat arrive,i see the three scrolls of Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba, where i can find the oyumi mención? Help me Please.

ReplyDeleteThere are unfortunately no depictions of such weapon, it is only mentioned in some document that I do not recall at the moment but must have been one of the two major gunkimono of the era.

DeleteHi! I have a question. Recently I've watched the 2017 movie Sekigahara centered around the titular conflict (and slightly too pro-Ishida for my tastes but whatever), and I've noticed that there are several cases of "unusual" weapons used in battle (for example in the titular battle you can see infantry armed with axes, hammers and kanabo), including crossbows. In one scene you can see soldiers crafting crossbows and crossbow bolts and in another one Ishida Mitsunari himself shots in the incoming opponents with several one-shot crossbows (with his attendants providing him with loaded ones) before going melee. From what I've seen they seem closer in the design to the western ones (including the large ring at the end of the weapon), so upon seeing them I wanted to hear your opinion on them. If you have the time, of course

ReplyDeleteAlthough you are correct about the lengthy history of crossbow use in China, it is crucial to remember that during the Ming dynasty, crossbows were seldom employed in warfare, and most often by South China ethnic minority who had little to no contact with Japan in the first place. Additionally, while you pointed out that a huge wooden crossbow would be awkward, it was in fact widely employed by ethnic groups like as Lisu, Yi, and, of course, the three-man Miao crossbow, which was notably enormous.

ReplyDelete