Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 4: Battle tactics

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 4: Battle tactics

The death of Yamamoto Kansuke during the 4th battle of Kawanakajima, from 永禄四年九月四日川中島ノ合戦山本勘介入道討死ノ図 by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

After writing in my previous post how the several types of units worked inside the Japanese armies of the late 16th century, in this article I want to describe the main battle tactics used by the whole army, which means how the aforementioned units worked together to achieve victory or to avoid being severely defeated.

I'm pretty sure that despite my efforts, I won't list all the various strategies available in that time period, mainly because the majority of them weren't actually codified or recorded, and some are hidden inside old war manuals; it's also worth writing that this tactics are only available on field battles, and not sieges or naval warfare.

Before reading through this post, I'll suggest you to have a look at my previous articles on the Sengoku period warfare:

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 1: Army & Formations

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 2: Cavalry Tactics

I'm pretty sure that despite my efforts, I won't list all the various strategies available in that time period, mainly because the majority of them weren't actually codified or recorded, and some are hidden inside old war manuals; it's also worth writing that this tactics are only available on field battles, and not sieges or naval warfare.

Before reading through this post, I'll suggest you to have a look at my previous articles on the Sengoku period warfare:

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 1: Army & Formations

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 2: Cavalry Tactics

Sengoku Period Warfare - Part 3: Infantry Tactics

As I said above and in the previous articles, this tactics will deal primarily with the late Sengoku period.

Nanadan no Hataraki - 七段の働

As I said above and in the previous articles, this tactics will deal primarily with the late Sengoku period.

Nanadan no Hataraki - 七段の働

This is a very common and ideal way to deploy and coordinate all the troops of the Sonae, and it is found inside the Senkou no maki (撰功の巻), a book of the Edo period.

When the two army are facing each other, and the distance is around 2 cho (218 meters circa), the gunners should fire against the enemy; the archers and the foot soldiers (pikemen and samurai) should advance further with the flag bearers, while the cavalry should wait in the rear.

In this first pictures, the gunners are already shooting against the enemy lines

After the first barrage, the army is supposed to move towards the enemy, and when the distance is around 1 cho ( 109 meters) there is a second barrage of the gunners mixed with archers fire; when the enemy is approaching further ( at 54 meters), the archers should quickly fire their arrows.

Here the circles represents the archers, who are shooting with the gunners too.

At this point, the gunners and the archers on the first line should break in two and move to the sides, as shown into the picture below, to support the forward moving foot soldiers.

When the two army are less than 30 ken (54 meters) far away from each other, the pikemen followed by the Samurai on foot* should charge in, supported by the ranged units who are still shooting against the enemy.

The flag bearer move forward too, and the cavalry, which is supposed to move after everyone else, are spaced out to the left and right, ready to charge.

The hollow triangles represents foot soldiers, while the "plus" the cavalry units. On the sides, the ranged units that have step aside to let the infantry charge.

After advancing 9 to 18 meters, the charging foot soldiers should move into a formation like the pointed tip of a sword; this is the vanguard ready to collide with the enemy, which is supposed to adopt a similar formation.

At this point, the distance in between is closer to 7 and 8 ken (12-14 meters).

Here the two armies are coming into clash; the "plus" are the cavalry units. On the blue side, I've depicted the hollow triangles as the pikemen and the hollow squared as the samurai, based on their proportions and actual position on the "push of pike" scenario.

Once the two lines of infantries collides and fight, cavalry should rush in to make the enemy team collapse with a flank or avoid the other horsemen to flank their own soldiers; once the enemy is retreating, the cavalry should pursuit and chase the fleeing soldiers.

This is the ideal & basic way of using at best the troops gathered in the Sonae, but it's rather simple and only consider two armies charging each other with the same scheme.

*: In the actual book, the Samurai were leading the charge, followed by the Pikemen; a classic Edo period glorified version of the reality.

It was most likely that the pikemen were the one leading the charge, due to the advantage of their weapon's length and their numbers over the Samurai on foot.

Kitsutsuki no Senpō - 啄木鳥の戦法

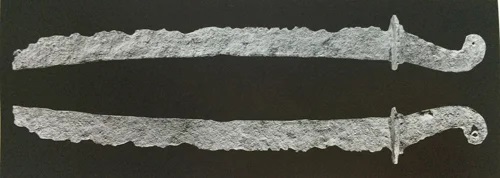

Better known as "The Woodpecker Tactic", it is traditionally attributed to Yamamoto Kansuke, although it is still debated whether or not he did elaborate anything similar or was in charge at the 4th Kawanakajima battle, when the tactic was created.

The flag bearer move forward too, and the cavalry, which is supposed to move after everyone else, are spaced out to the left and right, ready to charge.

The hollow triangles represents foot soldiers, while the "plus" the cavalry units. On the sides, the ranged units that have step aside to let the infantry charge.

After advancing 9 to 18 meters, the charging foot soldiers should move into a formation like the pointed tip of a sword; this is the vanguard ready to collide with the enemy, which is supposed to adopt a similar formation.

At this point, the distance in between is closer to 7 and 8 ken (12-14 meters).

Here the two armies are coming into clash; the "plus" are the cavalry units. On the blue side, I've depicted the hollow triangles as the pikemen and the hollow squared as the samurai, based on their proportions and actual position on the "push of pike" scenario.

Once the two lines of infantries collides and fight, cavalry should rush in to make the enemy team collapse with a flank or avoid the other horsemen to flank their own soldiers; once the enemy is retreating, the cavalry should pursuit and chase the fleeing soldiers.

This is the ideal & basic way of using at best the troops gathered in the Sonae, but it's rather simple and only consider two armies charging each other with the same scheme.

*: In the actual book, the Samurai were leading the charge, followed by the Pikemen; a classic Edo period glorified version of the reality.

It was most likely that the pikemen were the one leading the charge, due to the advantage of their weapon's length and their numbers over the Samurai on foot.

Kitsutsuki no Senpō - 啄木鳥の戦法

Better known as "The Woodpecker Tactic", it is traditionally attributed to Yamamoto Kansuke, although it is still debated whether or not he did elaborate anything similar or was in charge at the 4th Kawanakajima battle, when the tactic was created.

The legend says that the idea came to Yamamoto's mind while he was watching a woodpecker bird catching an insect through an hole inside a tree.

This maneuver is quite simple, and it's an high risk/high reward one. The main force is divided into two small armies; one is supposed to face the enemies and, through the usage of ranged weapons, provoke them and force to attack.

The other force instead should be placed at the rear of the enemy army, before any actual engagements start, and the two forces should close the enemy into a pincer attack.

The army that attacks on the rear could either surround the enemy with an un expected charge or cut the enemy withdrawal if the main army is strong enough to route it.

To perform at best this tactic, the main army that faces the enemy should be composed with gunners and archers all deployed behind some type of covers and protected by pikemen lines, while the second army should be composed by highly mobile troops, like cavalry units.

A classi depiction of the woodpecker tactic; while the enemy is engaged with the main army, it's going to receive a charge on the rear by the second force.

A classi depiction of the woodpecker tactic; while the enemy is engaged with the main army, it's going to receive a charge on the rear by the second force.

There is also another, very simple version of the tactic, which doesn't require to split the main force; the enemy army is only forced to directly attack through provocations. As simple as it might seems, forcing the enemies to attack when they are not comfortable to do so usually lead to an unorganized attack, which usually means defeat.

Although this tactic was meant to be used at the 4th battle of Kawanakajima by the Takeda against the Uesugi, the latter were able to understand the plan and by moving through the night, they flanked the main army, which was already split in two. The "rear" army arrived only late and the Takeda suffered heavy casualties; the legendary Yamamoto perished too.

Tsurinobuse - 釣り野伏せ

A very popular and famous tactic, associated with the Shimazu clan but also popular in the whole Kyūshū island.

This maneuver is a "feigned retreat", which allow a small army to lure into an ambush the enemy.

The main force is split into three or four separate armies, two/three hidden into strategical positions and a decoy.

The decoy army should engage with the enemy and feigns a retreat in order to redirect the enemy army into the ambush; when an army is in pursuit, usually loose cohesion and discipline. Once reached the other hidden armies, the enemy was usually exposed to crossed fire. The Shimazu were particularly deadly with their tsurinobuse due to the usage of trained sharpshooter and an high presence of gunners into the hidden armies which lead the ambush.

Tsurinobuse - 釣り野伏せ

A very popular and famous tactic, associated with the Shimazu clan but also popular in the whole Kyūshū island.

This maneuver is a "feigned retreat", which allow a small army to lure into an ambush the enemy.

The main force is split into three or four separate armies, two/three hidden into strategical positions and a decoy.

The decoy army should engage with the enemy and feigns a retreat in order to redirect the enemy army into the ambush; when an army is in pursuit, usually loose cohesion and discipline. Once reached the other hidden armies, the enemy was usually exposed to crossed fire. The Shimazu were particularly deadly with their tsurinobuse due to the usage of trained sharpshooter and an high presence of gunners into the hidden armies which lead the ambush.

Unlike the Woodpecker, here the "decoy" army should be made with highly mobile (and highly trained) troops like mounted infantry and cavalry units, while the ambushers troops should be composed of gunners and archers, with a line of pikemen that should face the enemy to stop its charge and allow the decoy to safely reorganized behind the allied lines.

The tsurinobuse tactic; in this moment, the pursuers have fallen into the ambush, whit sharpshooters hidden on the flanks and the decoy safely reorganized behind a line of pikesl

On paper it's quite simple, however the faint has to be realistic in order to work properly, otherwise the decoy might be worthless and suffers useless casualties.

It's a great tactics when facing a numerical superior army, and when performed properly, is able to route entirely an army due to the psychological effect of the surprise attack.

The Shimazu were able to perform tsurinobuse in several battles, despite being famous for their usage; however it didn't work against Hideyoshi during his Kyūshū invasion.

Sutegamari - 捨てがまり

Another tactic famously deployed by the Shimazu at Sekigahara, which probably was the main reason that allowed the clan to survive after the conflict.

The sutegamari is a form of tactical withdrawal that allow the main Sonae to survive when the battle is lost.

As soon as the army is withdrawing, specialized units of highly trained (and devoted) samurai, armed with arquebus and spears should detach from the rear of main army to fight the chasing enemies.

These small units were required to sit, shoot their guns against the enemy commanders and then charge straight ahead, to stop the momentum.

The sitting position was adopted to have a better aim while being hidden, which also add a surprise effect to the attack; due to this feature, these units were also called Zazen jin (座禅陣).

Here each zazen jin is deployed on the path of the enemy, ready to charge and sacrifice themselves to save the main army,

As bizzarre as it might seem, this tactic was extremely effective to stop the enemy army; the hidden units and the unexpected charge were the first signs of getting trapped into an ambush (like the tsurinobuse), which arguably was the bread and butter of the Shimazu.

Although these zazen jin did not survive most of the time, they were supposed to kill the enemy leaders and arrest the charge.

With this tactic, the Shimazu were able to survive and stop their pursuers, but with a huge effort; only 80 men of the 300 deployed were able to survive.

This tactic requires trained and willing-to-die soldiers to work properly, and at Sekigahara the Shimazu demonstrated to have those Samurai capable of fight until death to save their lord: not many clan had the same luck.

Kuhiki - 繰引き

Here we see again a tactical withdrawal famously used by the Uesugi clan.

The kuhiki, also known as kakari is rather simple and intuitive tactic; when the battle is lost and the army need to retreat, the main force is split into three/four forces. When the Honjin Sonae is on its way, the other three/two forces, which should be made with all the ranged units available should stand and fight the chasing enemy, to stop its momentum.

The Kuhiki; the line of defense it's clearly visible while the main Sonae is retreating.

This tactic was used to support the retreat of the commanders while preventing an unilateral attack of the enemy, and to minimize the casualties. In fact, unlike the sutegamari, the rear is fighting in one single spot and should withstand the enemy attack, rather than slowing it down.

Ugachi nuke - 穿ち抜け

By this point, the reader should be aware of the military prowess of the Shimazu clan, since even this tactic was famously deployed by them.

The ugachi nuke is a retreat inside a charge.Instead of retreating backward, and avoid the direct confrontation with the enemy, the main army adopt a very offensive formation like the Hoshi and charge straight ahead against the enemy ranks, to penetrate it and escape behind them.

In my sketch here it is possible to see how the hoshi is getting into the enemy ranks to break them and escape.

This tactic only makes sense when the enemy is surrounding the army into a pincer maneuver. With a wedge formation like the Hoshi, the men are all arranged vertically, which means that they had more momentum and could move faster.

The idea is to breakthrough into a weaker part of the enemy army, which is not an easy task to do.

It's an high risk/ high reward tactic, that allowed the Shimazu to save the day at Sekigahara, together with the sutegamari tactic.

Those tactics that I had listed are only a very small part of the several hundreds maneuvers performed by thousands of Sengoku armies, but are the most famous and documented ones; I hope that this article was informative enough!

For any question, feel free to ask in the comments; and if you like this post, please feel free to share it!

The tsurinobuse tactic; in this moment, the pursuers have fallen into the ambush, whit sharpshooters hidden on the flanks and the decoy safely reorganized behind a line of pikesl

On paper it's quite simple, however the faint has to be realistic in order to work properly, otherwise the decoy might be worthless and suffers useless casualties.

It's a great tactics when facing a numerical superior army, and when performed properly, is able to route entirely an army due to the psychological effect of the surprise attack.

The Shimazu were able to perform tsurinobuse in several battles, despite being famous for their usage; however it didn't work against Hideyoshi during his Kyūshū invasion.

Sutegamari - 捨てがまり

Another tactic famously deployed by the Shimazu at Sekigahara, which probably was the main reason that allowed the clan to survive after the conflict.

The sutegamari is a form of tactical withdrawal that allow the main Sonae to survive when the battle is lost.

As soon as the army is withdrawing, specialized units of highly trained (and devoted) samurai, armed with arquebus and spears should detach from the rear of main army to fight the chasing enemies.

These small units were required to sit, shoot their guns against the enemy commanders and then charge straight ahead, to stop the momentum.

The sitting position was adopted to have a better aim while being hidden, which also add a surprise effect to the attack; due to this feature, these units were also called Zazen jin (座禅陣).

Here each zazen jin is deployed on the path of the enemy, ready to charge and sacrifice themselves to save the main army,

As bizzarre as it might seem, this tactic was extremely effective to stop the enemy army; the hidden units and the unexpected charge were the first signs of getting trapped into an ambush (like the tsurinobuse), which arguably was the bread and butter of the Shimazu.

Although these zazen jin did not survive most of the time, they were supposed to kill the enemy leaders and arrest the charge.

With this tactic, the Shimazu were able to survive and stop their pursuers, but with a huge effort; only 80 men of the 300 deployed were able to survive.

This tactic requires trained and willing-to-die soldiers to work properly, and at Sekigahara the Shimazu demonstrated to have those Samurai capable of fight until death to save their lord: not many clan had the same luck.

Kuhiki - 繰引き

Here we see again a tactical withdrawal famously used by the Uesugi clan.

The kuhiki, also known as kakari is rather simple and intuitive tactic; when the battle is lost and the army need to retreat, the main force is split into three/four forces. When the Honjin Sonae is on its way, the other three/two forces, which should be made with all the ranged units available should stand and fight the chasing enemy, to stop its momentum.

The Kuhiki; the line of defense it's clearly visible while the main Sonae is retreating.

This tactic was used to support the retreat of the commanders while preventing an unilateral attack of the enemy, and to minimize the casualties. In fact, unlike the sutegamari, the rear is fighting in one single spot and should withstand the enemy attack, rather than slowing it down.

Ugachi nuke - 穿ち抜け

By this point, the reader should be aware of the military prowess of the Shimazu clan, since even this tactic was famously deployed by them.

The ugachi nuke is a retreat inside a charge.Instead of retreating backward, and avoid the direct confrontation with the enemy, the main army adopt a very offensive formation like the Hoshi and charge straight ahead against the enemy ranks, to penetrate it and escape behind them.

In my sketch here it is possible to see how the hoshi is getting into the enemy ranks to break them and escape.

This tactic only makes sense when the enemy is surrounding the army into a pincer maneuver. With a wedge formation like the Hoshi, the men are all arranged vertically, which means that they had more momentum and could move faster.

The idea is to breakthrough into a weaker part of the enemy army, which is not an easy task to do.

It's an high risk/ high reward tactic, that allowed the Shimazu to save the day at Sekigahara, together with the sutegamari tactic.

Those tactics that I had listed are only a very small part of the several hundreds maneuvers performed by thousands of Sengoku armies, but are the most famous and documented ones; I hope that this article was informative enough!

For any question, feel free to ask in the comments; and if you like this post, please feel free to share it!

Gunbai

Nice article as always! I finally got to see Tsurinobuse discussed in details.

ReplyDeleteI think a unique feature of Sengoku Japanese warfare is the fluidity of the formation of individual Sonae. Come to think of it, each Sonae much shift its formation to face different challenge, while at the same time coordinating with other Sonae in a larger formation. That's no small feat!

Thank you!! Although I have to say that despite the Japanese names that add some "uniqueness", these tactics were quite common in the world.

DeleteYes the Sonae are indeed amazing (and the main obstacle when someone is approaching the topic!) but they actually reflect the society of Japan at that time: the Daimyo had different vassals, each of them had the right to use a piece of land and men.

This is true also for the Sonae; the Daimyo was in charge of the whole army, which was divided into Sonae, all of them lead by vassals.

It was crucial the role of the Tsukai ban, the mounted messangers!

Come to think of it, most contemporary European military units equivalent in size to a Sonae consisted of one single troop type, or several closely related types (like halberdiers + pikemen). Since everyone in the same unit does the same thing more or less, there's no need to change formation too often.

DeleteEarlier in European history when feudal system was stronger, the army was apparently structured like Japan too......or so I am told.

Yes it is true, especially because the other European nations were unified more or less and started to have national armies; on the other hand, Japan didn't have an official national army until the Edo period.

DeleteEven at the times of Hideyoshi, the influence of Tokugawa was so big that he didn't partecipate at all for the Korean invasion, leaving any significant and skilled horsemen of Japan at home (which does kinda makes sense, horses are hard to transport by ships).

I highly value these articles, since it is so difficult to come by reliable sources regarding the less known side of ancient Japanese warfare. Would it be possible to make an article about the nagamaki (長巻)? I read somewhere (again, unreliable source) that it functioned as anti-cavalry, but was also strong against armour (especially the longer and heavier nagamaki which are more akin to naginata). Is this true? Would love to hear response!

ReplyDeleteHello and welcome to my blog! I'm glad you find my articles and my work reliable!

DeleteI'm planning to write about the Nagamaki as well as other Japanese weapons very soon! It's a very unique weapon and we don't know a lot about it. The main theory is that it was a much more user friendly Nodachi (longer handle = better leverage = easier to control).

Like many long weapons in Japan, it was used to deal against horsemen (like the Naginata) but it wasn't necessarily used to cut the horse's legs, but to unseat the Samurai.

I would also say that it wasn't used as an antiarmor weapon like axes or maces were (you could find more about these weapons here in this blog), but mainly to cut and thrust against unarmored target.

Thank you very much! That was a very helpful reply. I am looking forward to reading more of your articles!

Delete