Wantō (湾刀): Early Curved Japanese Swords

Wantō (湾刀): Early Curved Japanese Swords

This specific name is an umbrella term used to refer to every Japanese curved swords, although in this s artilce I'm going to present the very first types of said family, namely the warabitetō (蕨手刀) which differs from the usual curved Japanese sword of the later periods and all the variations that sprung from this so iconic and yet forgotten Japanese swords.

As a premise I would love to point out that this is definitely not my area of expertise, and it tooks several month to get the puzzle more or less correct; this topic is massive and it has not been covered as much as it should by modern publications, since most of the attention is given towards later period blades.

So this article is rather an introduction on the topic, as I believe there are much more reliable and authoritative sources than me.

However, I would love to say that this article was possible thanks to the majestic work of Carlo Giuseppe Tacchini, "On the Origins of NihonTo", a paper that is the main reference for the entire article.

Before drescribing those swords it is important to briefly talk about the political situation of Japan during the Nara and the early Heain period, so in between the 8th and 10th century.

In fact, in the 700s Japan wasn't unified under a central government and the north eastern regions were independent from the Yamato court which controlled the south west of the archipelago.

The Kantō region and the entire Tōhoku region weren't under direct influence of the court and had their own unique culture. While the Kantō people were still fairly similar to the ones who inhabitated the southern part of Japan and were gradually assimilated within the Yamato sphere of influence, the north was populated by the Emishi (蝦夷), a people whom are still mysterious and highly debated among modern day historian.

Emishi people from a 14th century depiction

In both regions there was a strong and vivid horse culture probably brought by Korean immigrants during the 3rd and 4th century, and the Kantō region was a source of skilled horse archers for the Yamato army.

It was within these regions and especially in the north that new swords models, native from Japan and independent from direct influences of the mainland were developed around the 5th and 7th century.

During the 8th and 9th century, the Yamato tried to assimilate both regions through political alliances, integration of these people in the Japanese society under the control of the Imperial court and ultimately through war. Those pieces of history, despite being extremely interesting, would not be covered here but it is important to highlight that it was through this contact that these types of swords spread towards the south east of the region.

Early History, V -VII century

It has been established by historians that the people in the north of Japan at the time had developed a slightly different type of iron smelting technology compared to those influenced by the mainland in the south east, and this is somewhat explained by different types of furnaces as well as different types of sword's designs.

The creation of this type of weapon, called warabitetō is dated 5th century, during the Kofun period; however, it gain popularity during the 6th and 7th century especially in the north eastern regions. Despite the fact that the people of the north had a consolidated and established net of trade with the mainland, there are no equivalent swords found there so it is assumed that it was a designed native to Japan.

The name of it is due to the fact that the hilt design which resembled a young bracken, with its iconic pommel.

These swords were quite short, in between 40 and 50 cm blade length on average and no swords exceeded 60 cm with the longest example at 58 cm.

On the other hand, they usually sport a strong curvature; more then one hundred specimens shows curvature and about 22 show a sori more than 0,5 cm deep, ten of them even a curvature between one and two centimeters, although straigh examples along the blade existed as well.

This curvature in fact might look odd to the untrained eye, because it is emphasized along the hilt, and this tsuka-sori concerns especially early examples.

A straight warabiteto sword; notice how the curve is mainly concentrated towards the hilt, a typical feature of later Heian period tachi.

These blades were intended as a cutting& slashing weapons, and this is clearly seen along the tsuka-sori, the width of the blade around the monouchi area, and the stepped kamasu-kissaki also found on the swords used by the Yamato people.

Also, the sori of the blade increases the overall curve of the weapon, which results in a better cutting ability.

The artisans who forged these swords applied therefore consciously a sori, and the emphasis of the latter led gradually to the emergence of a tachi-sugata, and therefore the warabite sword has to be regaded in the wider sense as the first step toward this development.

In fact, the peculiarity of this early curved sword is that the curvature is mainly focused on the hilt. This offset the line that connect the blade tip with the hilt and so the blade function as curved. However, the most common type of warabite sword has a strong curvature along the blade as well.

Warabite sword with curved hilt and curved blade.

It has been suggested that the development of this curved sword was related with the strong horsemanship culture of the regions during this time. However, despite the clear advantages of curved blades on horseback, the warabite swords were quite short to be used while riding, which is quite puzzling. There was however a trend of increasing the length of the overall weapon, which might give some credit to the theory although the swords remained somewhat shorter compared to the straight swords used in the western areas.

Maturity, VII- X century

These types of swords, quite influential in the eastern regions started to spread and evolve in different designs and styles which will establish the direct link with later nihontō. In fact, it should be clarified that the development of later Japanese swords it's much more related to this native warabitetō and later designs rather than to the continental chokutō, and I will explain briefly this link later, although it's quite self evident.

Around the late 7th and 9th century, we start to see two main variations of these short swords. One of the least know sword is the so called ryukozukatō (立鼓柄刀).These blades, like the warabite swords were either straight or curved, and the latter extremely resemble the shape of the later Heain period uchigatana. Given the fact that the hilt was still curved, the sword is considered a wantō.

Examples of ryuukozukatō swords

These swords are named like this because the hilt resemble the shape of a drum, and were usually short blades that didn't exceed the 60 cm. The hilt, like with the warabitetō was one piece with the blade, which are basically hira zukuri with a broad width and elongated point. The hilt itself strongly tapers around the center.

Another important, despite minimal, development was the introuduction of a kenukigata (毛抜形) hilt style in warabitetō blades.

Different hilts on warabitetō blades; notice the single piece construction.

Those blades are called kenuki-dōshi waribetō katana (毛抜同士蕨手刀) and they feature rectangular openings in the hilts which resembled hair tweezer of the period. The reason for this opening is unknown: some scholars believe its purpose to have been shock absorption, while others contend that it served simply to reduce the overall weight of the weapon.

A kenuki-dōshi waribetō katana. Notice that the tip isn't rounded but it's just heavily corroded.

This is probably the most important link with the later period tachi developed in the 10th century which are considered the first true nihontō.

Slightly different but still very much related are kenukigatagatana which are identical to the former model with the exception of the pommel cap:

A close up ok this style of hitl; however, the weapon is a tachi and not a short uchigatana as the one descirbed above, but it still give you the idea of the main difference.

Moreover, given the short nature of the blade, these were intended as single hand weapons.

This is actually where the link is established, since the following development in the late 9th century was the kenukigata tachi which will be covered in a next article with swords of the late Heian period.

However, it is quite neat and straigthforward to see the linkage and development from the warabite, the introduction of the kenukigata hilt and later Heain period blades.

Sketch taken from K.Friday that describe the relationship between warabite swords, kenukigata blades and later heian period tachi.

Finally, it is also suggested that curved warabitetō evolved and increase in length and were retained by the Emishi people who than migrated towards Hokkaido, giving birth to the Emishitō with the hilt construction being influenced by the works of the Yamato smiths, as we see that there is a nakago and the blade is supposed to be fitted with a wooden handle. These blades are even more similar to later periods katana and tachi.

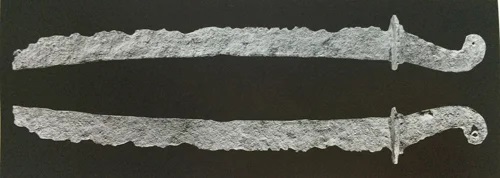

A series of well preserved Emishitō.

The transition from the kenukigata blades and the 10th century early style of what we will associated with Japanese Tachi is rather complex, still debated and will be addressed in the future, as I want to dedicate more space to the typology and the details of warabite swords in this particular article.

Up to the 10th century, both chokuto and warabite swords as well as the other blades examined here were still produced and used. However, after the development of the newborn tachi sugata of the 11th century, said swords with the exceptions of the emishi ones, confined into Hokkaido, weren't produced anymore in Japan and were completely and slowly replaced during the late Heian period by the famous nihontō.

Typology & Steel

The warabitetō can be divided into 3 main styles (although I'm quite sure more sub categorization exist), and quite surprisingly, the least popular styles is what is used to represent the weapon as far as I could tell, namely the shortest straight blade with a kissaki moroha zukuri.

Type 1 sword

The first type which consist of 80% of the swords excavated and it was extremely popular in the north, namely in the Tohoku area and on Hokkaido, but some examples were also found in the Kanto and Chubu areas. Generally it's in hira-zukuri configuration and has long blade compared to the other styles, with a sori along the hilt and often also along the blade.

Most tips tend to be a kamasu-kissaki. Wide blade and the tsuba is mounted from the tip and is held in place by the funbari (tapers from the base to the tip of the sword) of the base.

Type 2 blade

The second type is again in hira-zukuri and has short nagasa (blade length), but quite important, there is no sori on the blade, or actually we have a inverse uchizori like the ones found on chokuto of the same period.

The sugata looks like an elongated triangle and because of that it is also called "willow shape". The tsuba is mounted from the tip.These were discovered in the Kanto area, in the Chubu area down to the southern part of Fukushima Prefecture. Only three pieces were found in the Tohoku area. About 14,4 % of all warabite blades are of this style.

Type 3

The third type, arguably the most known one despite the low findings (4,5%!), is the one with the shortest blade length.

As I said before, they are in kissaki-moroha-zukuri, and are either hira-zukuri or kiriha-zukuri Hira-zukuri blades are short, and both hilt and blade have no sori while Kiriha-zukuri blades are medium sized or long and narrow and show quite a strong sori along the hi.

Given the fact that the majority of these swords had a sori along the blade, despite some examples of being essentially straight, we still consider them curved swords.

Examples of warabite blades that could be categorized into the second style.

Finally, it might be interesting discuss some details of the steel used for these weapons.

Most of them have a rather soft core inserted between layers of higher carbon content steel, other were made by more or less homogenous single billets of medium to soft carbon content.

Soft iron cores were essentially wrought iron in terms of carbon while the higer content was usually in between 0.2 and 03%.

These blades were usually hardened and they had an average hardness of 300HV to 350HV, in line with continental swords and lower compared to later period swords.

On the other hand, other part of the blades had the usually lower hardness value found on mild steel, around 150-180 HV.

Hence the steel can be classified as austenitic; however it is important to highlight that not every sword was hardened.

Speaking of hardening, the process was different from the ones used in later blade, and as a result yield different properties of the steel (a less harder edge, with less edge retention and more prone to rolling, but a more ductile blade overall) also due to the lower carbon content on the edge.

This process is described in old documents by the term “uzumi-yaki“ , which means to fire an object by inserting it completely in hot ash.

This might suggest that with this additional measure, eventually the blades were heated by sinking them entirely in hot ashes of the cooled charcoal fire. However it might also to be the description of a rehardening at lower temperatures, around 400° C.

There are few blades which shows the classic clay tempering traces although it's hard to consolidate this hypothesis since the blade are quite old.

So for the warabitetō and early wantō swords that's all! I hope you enjoyed the reading and I highly suggest you to have a look at the aforementioned paper,aa, which is a much more detailed work on the subject.Please feel free to share and leave a comment below for any question.

Gunbai

I just finished reading it. Very good.

ReplyDeleteThank you for putting the HV level of the sword.

For me the Warabite and the Japanese curved sword overall is very unique because it is a curved sword not developed by direct contact with the Steppe version.

Thank you so much!

DeleteI hope I was able to write an article with enough information. It is indeed very unique and the main starting point for Japanese swords, whom as far as we know developed curved swords without foreign influences.

Looking at the world's curved swords as much as I do, I'm starting to question the veracity of the so-called "Turko-Mongol saber theory" where all curved swords on the connected continent originated from/were influenced by "the generic steppe people" which disregards the various multi-ethnic and differing tribes of individuals on the steppes. Wouldn't it be more logical that something as simple and utilitarian as a single-edged curved blade/a big knife has been invented, reinterpreted, and reinvented by many cultures across history all with slight variations but sharing some very important key qualities primarily because of form following function? Honestly, being curved and single-edged is an overly generic quality that IMO should not necessarily indicate steppe influence when looking at continental swords, let alone any sword anywhere in the world.

DeleteIn any case, the Warabite-to/Wanto is indeed very interesting and at times looks very similar to certain types of Chinese dao I've seen...

Uh oh... I'm starting to see connections between overly generic qualities and implying a singular cultural origin to them biased by my own personal cultural lens! STOP ME BEFORE I PROPOSE THE SINO-TIBETAN SABER THEORY!!! XP

The Japanese sword is clearly different from Steppe sabre as we can see in the curvature and the cross section.

DeleteThe bent hilt on the Emishi sword is a strange way to add slicing motion to cuts.

Is there a reason this did not go under :myth 10: there were no variations of Japanese sword?"

ReplyDeleteXDXD This looks like a variation of Japanese sword.

Oh yes I actually have to finish that one!

DeleteUnfortunately I've changed my computer recently and I'm not able (yet) to use photoshop again properly, this is also there are less sketches in my article compared to the previous ones.

I really need to draw some stuff in order to deal with that myth, but hopefully I will address it in the future :'D!

Anyway this is indeed a variation of Japanese swords, and if you paired it with chokuto swords you can have quite a broad picture. But my biggest focus on that particular myth was the variation within later period swords, so from the 11th century onward ;)

Well would you look at that, i posted a comment under yours in the Linfamy video about the Emishi sword and i asked you for an article about it,then i came here and i see you have just done it!

ReplyDeleteI saw it just now! That's a good timing I guess :'D

DeleteHahaha anyone kind enough to tell me which video that is?

DeleteYes! This one:

Deletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbuQ9kkiHm0&lc=z23bghe4qx3iyfhrq04t1aokg5fnydo1mwqbkop1ptnbbk0h00410.1582846796052834

Something i am really curious about,is the way these weapons were used. The period of which we are talking about is antecedent to the any ryuha i know ,but there must have been a way in which they were taught to use them other than simply sticking them with the pointy end.

ReplyDeleteEmishi were mostly tribal mounted archer so i think they focused more on that aspect,but the yamato people must have had a way of the chokuto. Considering the period maybe they used chinese sources ?

Also before being relegated to cerimonial use weren't tsurugi used as weapons? Maybe in a manner similar to a jian?

One last thing, i don't really understand the peculiarity of the ryuukozukato, aren't they really similar to the warabite to? And of the latter,which is exactly the difference between the type 1 and 2?

Thank you in advance.

Knowing how very old weapons were used is very difficult since the only way to get to that would be through very fragmented textual or pictorial evidence which is rife with the many problems of reconstructing a martial art and interpretive problems. Heck, I don't think martial arts manuals were really even a thing that far back in history and teaching was done via oral transmission primarily.

DeleteConsider this: even in existing ryuha with lineages and historical documents for techniques, it's very difficult to say for sure whether the current practices of the school exactly match what was intended in the original transmission of the ryu since its only natural for schools to evolve, change, degrade, split, and reinvent over time. If that's the case with existing ryu that are 400 or so years old, let's not even imagine something even older than that dating before much well recorded history.

Same goes for Chinese martial arts which is why I don't think its possible to figure out "the way of the chokuto/tsurugi" without heavy amounts of guesswork which may not lead to the real "way of the chokuto/tsurugi/etc."

I think @JZbai addressed the first part of your question extremely well, but yes ken swords were used in warfare during the early times.

DeleteSo to answer to your questions, the ryuukuzoka has a more tapered hilt, usually thinner profile blades and a different pommel. The tip geometry is more akin to shobu zukuri and is actually very similar to later Heian period uchigatana. This pic kinda nail the point imho (left uchigatana and right ryuu. sword):

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EEG0a45UEAEKdK9.jpg

Warabiteto type 1 are curved in the blade as well, type 2 only in the hilt so the blade is straight. Moreover the type 2 has a width profile distal tapering so the base of the blade is larger than the point. Those are the main differences at the end

How does Amakuni Yasutsuna's story fit? Just an excellent swordsmith with god-like craftsmanship never seen before in making curved blades or paved the way for emishi swords reaching high-ranking japanese commanders at the capital city and shaping chokuto?

ReplyDeleteWell it's actually a legend in my opinion. Curved tachi didn't appear up until the late 9th and 10th century, and emishi swords started to spread only after the wars into tohoko (although it might be possible that some interaction was already going on across the 8th century).

DeleteFor example, one famous work attributed to Amakuni, the Kogarasu maru is very likely to be a 10th or 11th century sword. So it's really hard to fit this legendary figure into a historical framework.

We know that emishi style blades reached the court through the nobles who fought at the borders but that happened quite later as well compared to the time of Amakuni. So yes it's quite complicated trying to get something historical out of this man, unfortunately.

DeleteIndeed curved blades have been found in various archaeological cultures and indigenous groups across Africa, Asia and Europe since the bronze age. However Tachi and warabiteto look very different from each other, the characteristics shared between them could be just unknown archaeological finds

I don't think the tachi debuting in the 10th century sounds very reliable for 3 reasons

- the big clash between the emishi and Japan was in the 8th century

-Emishi actually own yayoi people (the forerunners of the iron age in japan) admixture otherwise they couldn't have cultivated oryza sativa paddy fields and built keyhole tombs, emishi and the japonic-speaking peoples had been battling each other long before 三十八年戦争, in short exposed to each other's arsenal countless times before the 10th century

-東大寺山古墳鉄剣 is curved, long, elegant... reminds me a lot of a stereotypical japanese sword

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/ファイル:東大寺山古墳出土_花形環頭飾金象嵌銘大刀.JPG

Not to say centuries older (2nd century AD) than any warabiteto finds

http://blog.livedoor.jp/myacyouen-hitorigoto/archives/47021579.html

I do believe Warabiteto came under the influence of tachi in response to the progressive expansion of the yamato army until eventually disappearing in honshu. So it is like the other way around and much earlier. The way.. ugly warabiteto turns into a gorgeous tachi

Deletein such a short time is very weird

I wonder why not much is said about curved chokuto

DeleteNumbers 2, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12

http://kakkou1210.stars.ne.jp/kodaishi/isonokami/yamauci1r1.jpg

For more info:

http://kakkou1210.stars.ne.jp/kodaishi/isonokami/futsu2.htm

I think that we should avoid using a evolutionary mindset when it comes to nihonto.

DeleteChokuto of continental design were used not only as a tool but also as a form of "Sinicization" of the Japanese court. The Yamato sphere was indeed heavily influenced by China and Korea up to the 6-7th century, when they started to develop their own culture with less Chinese and Korean influences due to the main events in the mainland.

Within this context, this is why we do not see adoption of Emishi sword features into the court prior to the 9th century. It took some time and what really made those new Japanese swords (late Heian period Tachi) popular were the predecessor of the Samurai that from that point onward became the main factors of Japanese warfare (after the unification of Japan and the dismissing of the national army).

These people were low ranking nobles tied with the Kanto and border regions in the north, far from the Court and I would say somewhat "discriminated" by the other nobles that lived in the capital.

Moreover, during those centuries (8th-9th) we can see a slow assimilation of those Emishi people into the Yamato cultural sphere, and so we had a mix of cultures and interaction of material culture.

This is what lead to the development of the first "Koto period" swords in Japan.

Moreover, the tachi you posted are really the "elephant in the room" when it comes to Japanese sword classification, because they have a inward curvature quite unique (uchizori), rarely found in some tanto and definitely not as exaggerated as in those example; the main problem is that chokuto are supposed to be "straight" as the name suggest 直刀.

Still I don't see many similarities with later period Japanese nihonto because the curvature is in the opposite direction and the pommel construction is totally different.

I might add some line of those style of sword in my chokuto article.

What I can say is that there is still much to do in this field in terms of research.

However I don't think that later Heain period design would have appeared earlier than the 9th-10th century because those Tachi, from the kenukigata onward, definitely carry the influences of warabite swords and the later blades associated with this design (kenukigatagatana and emishito). If such blades exister before, we should have found something given the Kofun burials.

But this is my opinion and I have to say that I still need more time to study this period and I find it somewhat puzzling in the sources themselves. It's far from being a clear and easy topic in the academic world.

I do believe that Japanese swords as we know them (nihonto) originated through the interaction between the adopted and refined chokuto style and the native Emishi design; but as you can see there are few missing link and trying to get a clear reconstruction is next to impossible I believe.

But I do reccomend you to read this paper: "On the Origins of NihonTo" by G.Tacchini if you can find it online. It goes much more into details compared to my article.

Deletehttps://1.bp.blogspot.com/-CPD_-Umh8UE/Xlb09XUjj-I/AAAAAAAABug/kq1DbV1EzlQQv0zphCuBWSg6J_01_E3dgCLcBGAsYHQ/s400/friday.jpg

I can only imagine that the third from the top added to a kogarasu maru would have given birth to the rest

Perhaps the swords I showed had different names throughout history.... in the absence of another term, I just called them curved chokuto (is chokuto a precise historical term or modern anachronism invented by scholars?)... they all date back to the 2nd century after Christ. Considering that perhaps the tachi was invented in the eighth century, the timeline is long enough for different developments to have occurred since the 2nd century, something like Amakuni Yasutsuna, if he or another person had invented the first tachi or not , anyway it is a misconception that tachi would be the first curved sword in Japanese history, curved bladed have existed in Japan since the 2nd century at least. Let's just say curved chokuto swords with their own separate and relatively unknown timeline weren't much of a mainstream weapon until the northern emishi war... i believe the emishi swordsmithing influenced indirectly at first via convergent evolution, battlefield analysis and competition, surely from the 9th century onwards the two techniques (north and south) merged following the rise of samurai and reached all of japan

According to Markus Sesko:

Deletehttp://imgur.com/gallery/WzuZRHw

Yes Chokuto is a modern term used to refer to straight sword of Japan produced in the Jokoto period. These swords would have likely be called tachi (大刀).

DeleteAlso it's true, curved sword in Japan existed at least since the 5th century with the warabiteto. However, I have some issue with those very inward curved chokuto that you posted. You see, during the 2nd century A.D. almost the entire production of swords relied on Korean and Chinese technology, either through immigrants doing the work or by later generation of Japanese smiths who studied under the Korean and Chinese masters.

These models of early swords were 100% based on mainland design and as far as I know there are no such example of strongly curved tachi found in Korea or China during the same period (or earlier ones - there was some lag from the creation of something in the mainland to arrive in Japan) - but I might be wrong here.

There was some experimentation following the Korean and Chinese trend (the introduction of the shinogi ridge, differential hardening, new composition of steel and new design of hilt and blades like the moroha zukuri) but I've never seen that kind of inward curvature being popular. Most of the time when we have uchizori, it is very subtle:

Here you can see a uchizori chokuto:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Seven_stars_sword_Sitenoji_rotated.jpg/1200px-Seven_stars_sword_Sitenoji_rotated.jpg

It's very subtle the inward curvature to the point that is hardly noticeable.

In the other case however it is very strong. Could it be that the swords went under some considerable stress and deformation through the ages and thus are quite bent? It might happen with so many years in the ground (many Europeans swords of the migration period are bent in the same way). It's just a theory, because they are really unique.

The same apply for the kogarasumaru; kissakimoroha swords existed but usually with not such long false edge and not that curvature which is typical of later tachi. I would question the dating; in my opinion the kogarasu maru is a sword produced in the 10th or 11th century, when tachi as we know them were already popular. There are indeed too many details that point out such period, like the curvature, the grain of the steel, the shape of the tang and so on. I also think that many sword expert think the same of this very unique sword

東大寺山古墳鉄剣 was actually imported yes and made in the Zhongping era china according to its signature, archaeology is just archaeology, a matter of investment, luck and time.

Deletekogarasu maru:

http://imgur.com/gallery/0esxHLv

we know of a drawing by 本阿弥光悦 ( 1558-1637) which shows a date and a signature. This drawing was later published again in 継平押形. The tang is quite corroded so we can’t make out any signature today but in better conditions for reading at the time. This signature perfectly reads: “Amakuni and taiho".

The Taihō (大宝) era is noted with the characters in use at the time of Amakuni, i.e. with (寳) for hō. The year is only partial visible, all we can see is a curved stroke to the bottom right. So it could be either an eight (八) or a two (弐). Because the Taiho era lasted only for four years, the eight can be dropped and we get the second year, i.e. 702. The smith Amakuni was also dated in old sword documents to the Taihō era and this would tally with the date of the Kogarasu-maru. All we get from the historical records is the mounting was damaged, also the hilt wrapping are loose and that the metal fittings through which the suspension was slung were broken.... no scientific evidences of an older blade that was later fashioned into a tachi have been found

Yes I know of the dating, that's the only hint that point out to the legend of Amakuni.

DeleteHowever, there are so many points that question the whole thing, not to mention that unfortunately the tang signature is not visible anymore (which might actually question the dating itself).

Still, even if we consider the signature, the tsukuri-komi in kissa-ki-moroha-zukuri and the characteristics of the jiba are typical for the workmanship of swordsmiths of central Japan.

Probably it must be regarded as a work of the Yamato tradition in central Japan, but the shape of the sword with regular sori along the blade, the naginata-hi, as well as the sori and shape of the nakago looks very similar to tachi-sugata of the Kamakura period.

On the other hand, the size and position of the mekugi-ana and the finish of the nakago-jiri something in common with the tangs of extant signed tachi from the very late Heian period (the tang was filed indeed).

It's very unique and totally different from the swords of the Soshoin. Virtually there are no features that speaks of 8th century for this sword.

Kōkan Nagayama states that according to accademic consesus, this sword is to be placed in between the 9th and 10th century, when the first tachi started to be produced.

He also argues for the shape of the sori and the funbari as main features that points toward this direction. I'm actually very keen on this theory, this is why I haven't talked about the kogarasu maru yet, because I wanted to talk about it with later period swords.

But to be fair, if new evidences are presented I will be glad to change my mind!

DeleteAh I see now

Deletethanks for your time and sharing knowledge!!

You're welcome! This blog is about sharing knowledge and ideas with the purpose of learning! So it's good that we have these comment sections in which we share opinions and sources; it's helpful for everyone. I'm still learning as well so it's always good to have more inputs.

DeleteAfter searching for Pre-Samurai Japan, I got a lot of thoughts in my mind about Japanese swords.

ReplyDeleteI found this large sword, this is said to be the largest ancient Japanese sword. There is also the large Kofun sword with 140 cm blade I think.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DaFxq6yVQAAcHs2?format=jpg&name=4096x4096

https://kougetsudo.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/0ec355d3240e2babefd017459f5944f1.png

Apparently the blade length is 223.5 cm and it is from 8th-9th century.

The progression of blades in Japan is strange. With such capability to create such Zweihander length blades, they never create something like the Zhanmadao until the Nanbokucho Period.

Instead, they progress to curved swords and even the curved swords become shorter as time goes.

I often heard that the Katana is said to be a poor sword because of its weight/length ratio or that the Japanese are unable to create longer swords because of their metal.

However, I start to think that the relatively short length of the Uchigatana and Katana compared to previous swords had their advantage.

The Ming Dynasty general Yu Dayou seems to respect the Japanese sword more than the sword the Portuguese used. Maybe the short curved Japanese sword is more useful in general purpose and instinctive to use than the longer European side sword, especially in ship battle.

By theway, I found a photo of Nara Period lamellar armor stored in the Shosoin.

https://blogs.c.yimg.jp/res/blog-1d-f9/tyokkomon/folder/1269985/13/40206713/img_4_m?1447923040

Its narrow, tall plates seems to be the predecessor of later Japanese lamellar armor.

It's strange when people said that Japanese armor and weapon design, considering that the Japanese changes in weapon and arms probably only stop in late 1500s.

I would say that from year 0 to 1100, Japanese armor and weapons change as much if not a lot more than European ones.

The closest thing to Chinese armor in Japan I found:

DeleteBugaku performers:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:舞楽図屏風_・唐獅子図屏風-Bugaku_Dances_(front);_Chinese_Lions_(reverse)_MET_DP141393.jpg

Notice chinese-style armor in the middle, meanwhile on the left exaggerated hats (or maybe just satirical) influenced by the Tang official headwear

https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/_taiheiraku1_left.jpg

The most gorgeously costumed dance of all the court dances is the one that represents warriors celebrating a victory after the establishment of peace. Over the costume of red and gold brocade is worn a suit of simulated armor in the old Japanese style, with epaulets of red and gold lacquered wood made in the shape of dragons’ heads

It is taiheiraku bugaku

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2017/04/06/bugaku-japanese-imperial-court-dance

https://blog.goo.ne.jp/fuga-buriki-can/e/722c7be1640bddf67311b5a489c934b6

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D2qQYlFWsAA0wsi?format=jpg&name=medium

http://gagaku-dvd.net/taiheiB001.jpg

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcQgTm-JyBIJbGlQ9dJorCNjQ8pq8_3IPVwCNk13W2_AX1cpMmI1

https://web-japan.org/nipponia/nipponia22/images/feature/12_5.jpg

Interesting sword; however if those are the real dimension, the handle is way too short. I suspect that such long sword were actually ceremonial pieces, made by welding several normal lenght swords and thus not functional at all.

DeleteI don't think that they had the technology to build such blade and to be fair anything longer than 120-140 would be extremely impractical for a sword in my opinion.

Also anything debate concerning length on sword is silly. Shorter blades have obvious advantages in terms of carrying and so on, and the Japanese used longer swords as well not only the katana (which to be fair could still have 80 cm of blade).

Yes those are keiko lamellae! I do agree as well, there were a lot of arms and armor designs being tested in Japan by that period.

@henrique nice pictures!

Thank you for sharing! Japanese artist had access to Chinese art during various time period so it's not surprising to see such depiction. Even the famous manual Wubeizhi arrived in Japan as well during the Edo period.

@gunsen

DeleteThey are literally wearing that armor (as seen in the last pictures), it is not just a depiction, bugaku theater is a 8th-century relic with some changes over time... it is still interesting to notice the tang official headwear in the first pic (gives an idea about how old). Ted

Shawn was informed during his consultations at the imperial household

"simulated armor in the old Japanese style"

Similar helmet on the bottom right hand corner

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0e/Shotoku_Taishi_k.jpg

@henrique I would call them more like "costumes" but still I'm not surprised to see such design from the Tang dynasty surviving in Japan. After all we have religious statues too with the classical depiction of foreign types of armor.

DeleteThat's the most classical form of warrior dance/太平楽 (not to be confused with 剣詩舞) yet existing in Japan... it was originally performed by the high-ranking ritsuryo military commanders at the imperial court. The Samurai were no different in following the ritual:

Deletehttp://imgur.com/gallery/aLhP0S9

http://maturinookkake.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-1597.html

https://mainichi.jp/articles/20160404/ddl/k06/040/207000c

https://pinterest.com/pin/2885187234222331/

@Gunsen

ReplyDeleteAfter I look at the website where I found the sword photo, I realize that I miss a translation.

https://www.narahaku.go.jp/exhibition/2018toku/kasuga/kasuga_index.html

The blade length is 223.5 cm and total length is 270.5 cm. That means grip + sword guard length is 47 cm.

I translate the website with Google translate and get the info that the sword was given to someone in an eastern expedition probably to fight the Emishi, but I think it is better if you read it yourself as Google translation often miss the mark.

This is the Kofun sword I mentioned earlier. It is 150 cm long.

https://www.realmofhistory.com/2016/10/27/6th-century-tomb-longest-sword-japan/

So as long or slightly longer than a claymore and around the lower range of Zweihander.

Quite interesting indeed!

DeleteI do believe that the first swords might have actually been a ritual offer as it was gifted to a shrine later on (If I have understood correctly).

What we could say about the functionality of the sword is related on the structure: if said sword would have been made by welding 2 or more "smaller" swords it is not intended to be used. However I don't think we will have these info as it will be a very aggressive procedure.

Anyway it might be that the technology of developing this type of sword existed, but I assume that they would have been extremely impractical on horseback (which was how to nobles fought back then) as well as very costly (again speaking of the very long ones).

The reason for Odachi to be developed in the 14th century was the shift from cavalry to infantry tactics and so the noble warriors could afford "fancier" and longer weapons to fight on foot.

There are some depictions of these swords being used on horseback but I think that this is only doable with the smaller Odachi.

A sword longer than 120m is definitely intended for foot combat.

So these swords might have been more of a status symbol for the period in my opinion, because the people who could afford them usually fought on horseback as mounted archers or as "shock" cavalry in the 6th century and so they usually would have carried shorter sword (but still in the range of 70-80 cm of blade lenght).

I would be interested in how Japanese cavalry in the Kofun, Asuka, and Nara period fought before the widespread adoption of mounted archery.

ReplyDeleteI think those longswords could be used in anti-infantry like Claymores or anti-cavalry role for cutting horse legs.

I found out that Tachi and Uchigatana were used as pairs just like later Katana and Wakizashi.

When did the use of 2 swords became popular and were they used in battlefield?

By the way, what do you think of the armor comparison I sent you? It is still very incomplete, especially the Japanese parts. I am trying to produce the image of generic warriors instead of the best equipped ones.

Just 2 days ago I found out that Han Dynasty cavalry armor do extent to the ankle.

https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_1200,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/barakatgallery/images/view/6a86dc5c9cef6161022bb2c9d441c559j/barakatgallery-a-pair-of-han-dynasty-painted-pottery-seated-horses-with-detachable-riders-206-bce-220-ce.jpg

This make my theory that Chinese full body armor start during the 4th century Jin Dynasty wrong and set the starting point back to the Han Dynasty.

As far as we know, when cavalry as a concept was introduced in Japan we are talking about the about the 5th century and the 6th century.

DeleteK. Friday states that early cavalry forces "drew closely on Chinese shock cavalry models" in the sense that they were heavily armored but at the same time, we can read through "The Introduction of the Art of Mounted Archery into Japan" by R. Hesselink that said cavalry was indeed composed by mounted archers from the start and it was imported through experts coming from China in the 5th to the 7th century.

It is in the 7th century that we could see documents of the Ritsuryo code describing mounted forces armed with bows and arrows.

Anyway I'm actually quite against the theory that Nodachi or any type of two handed swords could be used effectively against cavalry in the sense that you could cut horses legs.

The best way to stop a cavalry charge is a solid formation with long weapons (or a formation of foot archers protected by fortifications/pikes), and eventually if the horsemen are stuck, shorter polearms that could dismount the riders or harm the horses at a reasonable distance (but only if the rider has troubles in maneuver the animal in the first place).

If you think about it, stepping aside from a charging horse and cutting its leg is a superhuman skill (and quite ineffective one compared to a wall of spear) and a two handed sword could do very little harm to a mounted archer without a dense formations backing these foot soldiers (moreover, it would be hard to use the sword in such situation).

Also, having a pair of two swords, one shorter like a dagger and one longer was quite common across many cultures. As far as I know, having two swords became quite common in Japan when we see the Samurai emerging as a social class dedicated to warfare, so in the 9th-10th century more or less.

As far as your work is concerned, I think it's good but as you said it's not complete and hoenstly I don't have that much of expertise outside Japanese armor (and to be fair, I don't consider myself an expert at all as I'm still learning a lot!).

However I haven't check the entire document because I've been so busy during the last 6 months so I have very little time to dedicate at almost anything I would like to do, unfortunately!

But I saw that you didn't include for example all the styles of different cuirasses or helmet designs developed during the Sengoku period, like Sendai or Okegawa do and so on. That would be intersting to include if you manage to have time!

@gunsen

DeleteRegarding the historical horse studies

Well, indeed kofun shaffron finds:

https://pinterest.com/pin/514465957403753678/

https://ameblo.jp/kodaishi-omoroide/entry-12388783795.html

https://www.city.koga.fukuoka.jp/cityhall/work/bunka/bunkazai/funabaru/shutsudohin/001.php

as you wrote above

"In both regions there was a strong and vivid horse culture probably brought by Korean immigrants during the 3rd and 4th century, and the Kantō region was a source of skilled horse archers for the Yamato army."

http://imgur.com/gallery/fxBfb63

More than 532 Jomon shellmound sites have been noted to have contained horse bones, starting about the time of Late Jomon. Experts say that the Jomon era horses were small to medium-sized horses, judging from the skeletons and teeth unearthed from archaeological sites such as Shell Mounds. The small horse had a shoulder height of about 110-120 cm and is thought to be the same as the Tokara uma which inhabited the Ryukyu Islands.

Indigenous horses were present in the jomon period as much as yayoi. However what happened to them isn't for sure, cross breeding it seems. During the Meiji Era larger purebred horses from Europe and North America were imported to increase the size of Japanese horse and make them more suitable for military use. To encourage this the government introduced training classes throughout Japan to increase the use of horses in agriculture. The goal was to motivate farmers to breed larger horses to ensure a supply for the army. Foreign breeds imported included Thoroughbred, Anglo Arabs, Arabs, Hackney and several draft breeds including Belgian and Bretons. Two recognized breeds, Kandachi horse of Aomori and the Yururi Island horse of Nemuro, Hokkaido, are the descendants of native horses crossbred with larger European horses. The result of these many importations was the almost total disappearance of local Japanese breeds except in very remote areas or on islands. A second wave of the japanese horses' mass extinction since the kofun era

Light emishi cavalry could be traced all the way back to the pre-kofun breeds, not much of a peninsular achievement.

Cross breeding is such an old phenomenon, which could explain a lot of puzzles

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_horse_domestication_theories

https://www.academia.edu/8378646/Bhimbetka_Horse_with_riding_10_000_years_old

https://thehorse.com/19099/researchers-reveal-chinese-horses-origins/

" Zhao added. Their research confirms that these small breeds do also have specific origins in local ancient stock originating in current-day China. “This novel maternal line may origininate from the horses domesticated in China,” he said.

The indo-european single origin theory didn't invent horsemanship... rather superior horses in strength, size and stamina.. chinese, indians and middle easterners highly prized central Asian horse over their owns. In the Chinese case they were more known as heavenly horses...

The former range area of wild horse is attested all the way between great britain and japan through fossils, bone art, paintings and yeah cave art from across Eurasia depicts people on horseback as well:

This is near Mesopotamia:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cave_painting_in_Doushe_cave,_Lorstan,_Iran,_8th_millennium_BC.JPG

Figure 24

http://imgur.com/gallery/VD7BFMI

The Iranian plateau is only reached by indo-europeans with and after the andronovo culture.

Back again:

http://mengnews.joins.com/view.aspx?aid=2907709

Cataphracts were the standard in all over Korea, a bit logical to think realizing goguryeo's long-term military superiority over both silla and baekje. It may be that Japanese indigenous prehistoric horses may have interbred with the ones introduced from the Mongolian stock ( 3 Korean kingdoms) and their genetic signals undetectable or lost in the present ones though...

@Gunsen

DeleteSo the Japanese didn't adopt mounted archery from the Emishi?

Didn't the Japanese had difficulty when facing the Emishi becuase of their mounted archer?

As far as I know there are probably several reasons for using 2 handed sword against cavalry. In Historum, there is remark that in mainland East Asia, cavalry could outnumber infantry forces in some battles. This pretty much almost never happen anywhere else in the world in any period.

A single pike is only usable against one horse or human, after they are impaled, the pikeman cannot easily get rid of the body sticking to the pike. This is before we factor the fact that a single rider could have several horses or that the horses could be armored.

Horse armor often leave the leg uncovered and a cutting attack do not let the body stick to the pike.

Making pikes useless through various means only need to be done in one section of the formation for the cavalry forces to break through the formation.

Of course, as there are no modern reconstruction of such battles, we can only guess on how such sword are used or if such cavalry superiority are true.

On using the sword, I think a formation like the one used by Billmen could be used, that is to create a column and let the cavalry passed through the gap. The soldier wouldn't need to swing the sword, just held it horizontally. It could also probably be held like short pikes if need be.

In my opinion, the mass number of cavalry or armored cavalry, advanced metallurgy and strong infantry tradition is why such sword are developed in East Asia.

Sometimes there are records that show really effective use of 2 handed weapons like an account where a Tang commander kill several (probably fully armored) Tibetan soldier with each swing of his Modao.

Using 2 swords together is different than having 2 swords on a person. Roman legionary could have a Pugio and a Gladius/Spatha, but he did not use a Pugio in one hand and a Gladius/Spatha in another.

I will add Japanese cuirass types into my compilation.

@henrique

DeleteThe problem with Japanese history in going so back in time is that we don't have recorded documents of that period, let alone specific ones dealing with Emishi cavalry. It is very possible that said tradition of horsemanship emereged before the 5th century, but as far as we know the Yamato got in contact with this type of skilled warriors only when they established themselves as the main central government in the country.

The accademic consesus on the topic is that while horses existed in Japan already in the Jomon and Yayoi period, didn't play a role in the military up until the relationship with the Mainland started.

@Joshua

The Yamato army that faced the Emishi was composed by 95% foot soldiers consrcipted from the farmlands and by 5-10% elite nobles who fought as mounted archers as far as we know from the sources of the period. They didn't adopted that form of combat from the Emishi, but the latter were simply better at it as far as we can tell.

The main issue that the Yamato army faced was the fact that they had to face an army composed entirely by this type of troops, which was highly mobile and knwo the terrain way better. This resulted in constant raid and skirmishis in which the main foot soldiers given their skill and training suffered heavy casualties and so the court decided to adopt the Emishi model, hence only hiring skilled mounted archers from that regions ( and especially the Kanto, which was under some form of vassal relationship during the Emishi war). This resulted into smaller armies, but more skilled warriors.

I see your points in using a two handed swords against cavalry, but I do believe that it's still rather inefficient compared to a pike formation. Pikes are most useful to fend off cavalry charges rahter than impale the horses, so they prevent a charge by the means of intimidation and because it would be a complete waste of time and resources. On the other hand, given the reach of a nodachi, you could have the same effect as the weapon is much harder to wield effectively.

They might be useful against horses when the cavalry charge is already hampered or the horsemen is unable to use his mobility properly, but at that point any weapon could be useful and a glaive such as a Onaginata could serve the same purpose.

What I do believe is rather hard to do is to cut leg horses while they are moving.

Again, I'm using my knowledge on the Japanese warfare of the period, and while I reckon that these two handed sword might have been used in China against horsemen, I can't see them being more effective compared to other weapons at least in Japan.

But sooner or later I will write an article on the nodachi and explain my opinions there!

Good work on article here's some works on the evolution of swords, I forgot to give them to you not sure if you'll find any useful information but here two learn Japanese though.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.mokuzai-tonya.jp/05bunen/zuisou/2005/08nihontou20.html

http://www.hanniew.com/C-SO00504.htm

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://www.militaria.co.za/articles/Examining_the_Origin_of_Soshu-den_old.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjKyLic96rlAhUnU98KHdwhBWUQFjAAegQIBxAC&usg=AOvVaw1wg2JTODZYWnLQU-CYnbOb

If I could say a few things about the horse part here's an article I found.

https://www.lingualift.com/blog/japanese-horse-breeds/

"it is believed that at least one horse breed(Kiso) is indigenous to Japan,"

And I disagree with R. Hesselink, first off we know that Emishi were the ones that develop horse archery with that and their guerrilla tactics is what give them the advantage over their enemy, it is when the Japanese army started adopting their tactics did they started to turn the tide against them, I looked up the Ritsuryo code and well I may have missed something I found nothing that mentions horse archers even then it could have been something that was added later.

Thank you for the additional sources, I will look into them!

DeleteWell we know that horse archery was already the main martial discipline developed by some of the Yamato nobles that could afford horses and time to train by the time of the Ritsuryo code. The Emishi did developed horse archery as it was a main and rather popular martial discipline all over East Asia at the time, and we know that they were better at it compared to the Yamato soldiers but what should be clarified is that the Yamato didn't adopt horse archery from the Emishi, they adopted their army composition.

It is actually documented by the Ritsuryo code;

from K. Friday :

"The state did try to maintain as large a cavalry component as possible, but the effort

ran afoul of major logistical problems – in particular the formidable time and expense

required to train recruits in the extremely complex skill of manipulating bow and

arrow while on horseback. It was simply not practical to develop large numbers

of cavalrymen out of short-term, peasant conscripts. The ritsuryō authors’ solution

to these problems was to draw cavalry troops from among elites who acquired the

necessary equestrian and archery skills on their own, stipulating that, when new

conscripts were assigned to companies and squads, “those skilled with bow and horse

were to be placed in cavalry companies; the remainder were to be placed in infantry

companies” ".

Before the war, the Yamato had built an army pretty much composed by many infantry soldiers drafted through conscriptions which were hardly effective at all given the lack of training and discipline, so once the lesson was learnt, they dismantled the army and relied on the usage of these professions (a.k.a. nobles mounted archers) to deal with military affairs. They reduced the army size but greatly enhanced the quality at the cost of slowly losing the "monopoly of violence" as these clans gain power.

When did the kenukigata tachi first appear? This page says the late 9th century but I thought they were only first created in the early to mid tenth century {about 930 and onwards}. Yet, there is a sword of this type from the late 9th to early 10th century claimed to have been used by Sugawara no Michizane in a shrine. Still, this could be just that, claimed. Not verified. Is anyone here familiar to to when this type of sword was first made?

ReplyDeleteYou might actually be right, we cannot reliably identify kenukigata tachi before the 10th century; my bad, I'll correct the mistake but thanks for noticing that, much apprecciated!!

DeleteThe first curved swords of Japan are bronze ones dating back to Jomon period, curiously also found in the same northern region of Tohoku

ReplyDelete