Japanese Swords "Mythbusting" - Part 1

Japanese Swords "Mythbusting" - Part 1

Oyamada Bitchu no Kami Masatatsu 小山田備t中守昌辰 holding a Japanese sword while facing a volley of bullets, from Koetsu yusho den Takeda-ke nijushi-sho 甲越勇將傳武田家廾四將 by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Hello everyone and welcome back!

The title is already quite self sufficient to explain the topic of this article, but I would like to write few forewords before starting this long but needed post on Japanese swords.

First of all, for the usual readers, I have to apologize for the long time period with no post nor articles: currently I'm moving house in another country, and without being boring, this is a long process and requires some time, unfortunately. Nonetheless, I'm trying to stay as active as possible and for those who are waiting for an article or a reply to a comment, thank you for your patience and again, sorry for the delay.

Another important premise is that this article won't be the average "katana mythbusting" article were the pop-culture idea of a katana (and Japanese swords in general) is torn to pieces; we don't need more of these, there already plenty of debunking videos, blogs, articles and so on talking about "how the Japanese swords is not made with supersteel" or "how they won't cut into other swords" and most importantly, that they are just swords.

We all know that, luckily.

Indeed, I think that with the needed wave of "debunking katana arguments", the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, creating new myths which are meant to downplay the Japanese swords, and those are the myths I will address here.

Moreover, I have already explained in detail some of the following myths, so for those who would like to know more, check the links throughout this article!

And finally, this would "ideally" be a top 10; in the first part I will start with the first 5 common myths I was able to came up with. I have already a following list to comment and finish, but if you have more ideas, please feel free to comment here below! I'm pretty sure that most of the "requested" myth to address would already be in my list, but if we came up with more, this might have a part 3 as well.

Now let's get to it!

Myth 1: Japanese swords were made with pig iron/ inferior steel quality.

This is one of the most common sentence you can find in a random internet comment which talks about the katana.

And yet, in a historical context, it is very far from being true.

Of course in a modern day context, with 21st century technology, 16th century Japanese steel in comparison is definitely inferior.

Just like 16th century European, Indian, Persian or Chinese steel is inferior to modern steel, because we have more than 500 years of progress.

But through the lens of 16th century technology, the amount of impurities (called slag) found on Japanese steel used for swords was not higher, on average, in comparison with other cultures swords. Sure, it is possible to have a wide range of quality within Japanese swords, but high quality swords were definitely worth it.

A Japanese tatara - the first step of the traditional creation of Japanese steel.

I have already talked about the quality of the native steel sources found in Japan and the smelting processes they had during the feudal period, but two common misconceptions used to "explain" why Japanese swords supposedly were made with low quality steel is the fact that they more often than not used satetsu (iron sand) and a bloomery smelter, the kera oshi tatara.

However, in reality, while satetsu wasn't the only source available, it wasn't even that bad in the first place, and moreover, in Japan an indirect steel making process was known (zuku oshi tatara) and widely used, so decarburized cast iron was used for blademaking (like in China and in Europe), which means that both assumptions are not valid to support the statement of Japan having/producing bad historical steel. Again, I did plenty of research on this and you can find my results (with references) in my "Iron and Steel in Japanese Arms&Armors" series.

Another widely used statement is that "katana were made of pig iron".

Again, this is simply not true.

Pig iron (or cast iron) has a carbon content higher than 2% and thus is very brittle and unsuitable for blademaking.

According to every single swords analyzed, there is no evidence that such high amount of carbon was found in the edge of Japanese swords.

Moreover, pig iron was decarburized before using it to make swords: this is the exact same process used by the Europeans to make their swords after the 14th century alongside bloomery production (which was still widely used there up until the 18th century).

A modern picture of pig iron made through modern industrial process.

Another funny contradiction to this widely used theory is that occasionally, you can find the idea of Japanese blade makers to not have a high temperature smelter and using pig iron in their blades; however, to consistently produce pig iron (or cast iron) in the first place, you need a high temperature smelter. In fact, the whole concept of blast furnaces is to produce cast/pig iron and then decarburized it into steel!

Myth 2: The curvature is not intentional but generated by quenching

This is another famous misconception used to explain the fact that Japanese swords are usually curved, and unfortunately is taken as true even by some student of Japanese swords.

While it is true that the differential hardening process creates a curvature, this is not neither the main process or the factor that decide the degree of the sori (反り).

A beautiful screenshot of the queching process traditionally found on Japanese swords.

In fact, the bladesmith decides before and after the quenching the design of the curvature by forging the sword with a convex (or concave) curvature and then adjusting it later after the blade has been quenched and prior to the final tempering. The latter process has even a name and it is called sorinaoshi (反り直し).

Japanese blades in fact could have different degrees and positions of the curvature, or no curvature at all.

This is quite evident when we compare Heian period tachi with later straight Kinnoto (勤皇刀). Much of the style and design of the curvature was dictated by the fashion and functionality of the time period.

The idea that the curvature was applied with a random process and without intentional decision making is thus false; and this led us to another myth.

Myth 3: The curvature doesn't add any benefits.

This is again a very popular statement, and it is often used in conjunction with the last myth I've discussed to explain the shallow curvature found especially on katana, but it doesn't really follow any kind of logic.

As we know, the process of Japanese swordmaking allow the maker to decide the degree of the curvature as well as to make a straight sword.

So why bothering adding the shallow curvature if that didn't have noticeable effects? Moreover, beside the fact that there are few degrees of curvatures find on Japanese swords - so generalizing is already a bad idea - not every of them is shallow (not to mention straight ones), the same design is also found on late European sabers and in some types of kriegmessers.

The effect of curvature in blades is still very disputed, and even more if the curve of the blade is not very deep.

But having a curvature is a tradeoff, because you are losing thrusting power in some way, since a straight sword has a much easier time when it comes to this particular motion.

So in a context where weapons were constantly tested in and improved in battlefields, it doesn't makes sense that the shallow curvature found on katana (and others types of swords) is only detrimental.

A Bizen Osafune sword with a moderate curve.

So, while it is stille very debated, it is worth starting with the fact that a curved blade (even if not dramatically curved) helps with draw cuts and slashes: when the blade is cutting and meet another object, the curvature aid with the movement and create a slicing motion (drawing or pushing the edge along and into the target medium). This is effect is increased whit greater curvatures (at the cost of losing thrusting efficiency), but still even a slight curvature would help with that.

But it's not all there; a curved blades has an advantage in the cutting motion because the curvature tends to redirect the blade towards the edge line.

To put it simply, when swinging a curved blade like a katana, you can feel that the blade naturally want to get proper edge alignment with the target.

This is quite important, because wrong edge alignment leads to ineffective and poor cut and could damage the blade as well.

So even a slight curve does help with consistency in the cut because of the natural edge alignment orientation. This is a massive advantage when it comes to cutting reliably different targets in different situations.

A modern reenactor cutting tatami mats with Japanese swords - taken from this video.

Does it mean that straight swords are inferior in the cuts? Absolutely no, in a general context.

The fact that curved blades have a more natural alignment doesn't exclude the fact that a straight blade could have a perfect edge alignment too with proper techniques.

Curved blades are more user friendly compared to straight ones; but still, a lot of people forget the fact that even with 10 years of cutting training, techniques could be hindered in a battlefield scenario by the fact that in a historical context people fought for their lives against living opponent and not tatami mats.

This is very important to consider, and the natural tendency of curved blades towards proper edge alignment in this precise scenario is indeed an advantage.

This is exactly how bad edge alignment looks like and how can lead to a failed cut. From a very highly suggested video of Matt Easton of Scholagladiatoria.

Finally, curved blades, even if the curve is shallow, have an easier time at displacing other blades in a bind: rotating a curved blade moves the whole blade and/or tip a good distance depending on how curved it is. A straight sword has to use a larger motion to move the tip and blade the same distance.

This is somewhat hard to understand without sparring experience, but is a well known fact known by European sword masters of the 16th and 17th century as well as modern Hema and Kenjutsu practitioners.

In fact, this is what Francesco Antonio Marcelli has to say about the curved swords of his period:

"The sabre is not made of three parts like the sword: forte, terzo and debole, it is considered to be made of just one part, which includes the whole blade, because it has all the same strength and quality. So, the sabre is considered to be all forte, because you can hurt and defend with any part of it, be it the point, the middle or the one close to the hilt.

You can severe the enemy with any part of a sabre’s edge (I say edge, because the sabre doesn’t hurt with the point), all parts have equal strength, with no quantity variation, because the blade doesn’t vary in quality."

With this knowledge in mind, Marcelli is saying that the curved blade of the saber makes it excellent at displacing opposing blades without being as easily displaced (the forte is best at that).

However, it is worth pointing out that this fact might be related to the way the sword is balanced rather to the curvature itself (a point that still stands in the case of Japanese swords, since they tend to be blade-heavy). And although is a little bit of generalization here, it is worth pointing out that said features are shared with Japanese swords as well.

Moreover, the curve helps with the movements involved in iaijutsu; this is still disputed, but a curved sword has a natural cutting motion when it is drawn from the scabbard, and it has a larger centre of percussion to the blade while also maintaining a large area to slash with it. So there are plenty of benefits derived in the katana's "typical" curve which are often either overlooked or forgotten.

A very simple and yet effective diagram of the types of sori found on Japanese swords. Although they depended on the time period, it is not rare to find all the 3 types of curves in 16th-18th century Japanese swords. Taken from here.

Myth 4: The disc handguard serves no purpose

Another widely discussed point is the rather minimal handguard found on Japanese swords, the tsuba - 鍔 .

The first thing that I want to point out is that the tsuba is a handguard that can still protect the hand in a considerable way, despite it is often described as a useless piece - pretty much as it is not there at all, which is obviously false.

Another thing to consider is that bigger tsuba existed too and they can cover a good portion of the fist; some of them have a diameter of 10+ cm which is more than enough to protect the hand against cuts and strikes when the point of the blade is facing the enemy.

Bigger tsuba are often found on longer Japanese blades, like nodachi.

A quite big tsuba also known as 大鍔. Notice how big is the handguard compared to the blade - this gives you an idea of the dimension!

Yet at the same time is quite interesting that in Asia (and especially in Japan) we do not see fancy or heavily protective handguards (crossguards are not very common at all): this is easy to explain in the context of sword and shield usage in China and Korea and other Asian countries that often used small, round handguards.

However, while in Japan shields were used, they were never really as popular as in China or Korea, so there should be a practical reason for the lack of a considerable handguard/crossguard development (in swords!); and in fact there are some.

If you have paid attention to the previous myth, you would have already read that the curvature, the fact that Japanese swords are balanced towards the tip (blade heavy), as well as the two handed handle which can increase the leverage, make katana and Japanese swords in general very good at displacing opposing blades without being as easily displaced.

This means that a Japanese blade is less likely to end in a bind with another sword (which is where a crossguard might be very useful) and that most of the actions could happen towards the final portion of the blade.

With this things in mind, it is easy to see that using a Japanese swords as it should be used does allow the user's hands to be relatively safe and less likely to be hit (and if that happen, a tsuba could still catch most hits directed to the handle).

Don't get me wrong, I don't want to say that a tsuba can protect better than yout average late 15th century European crossguards, but I'm quite confident that Japanese swords (and a lot of Asian curved swords with similar handguards ) don't need a crossguard to be effective at keeping the hands safe, and not only for the aforementioned reason.

A crossguard, as much useful as it is, it's a rather simple and easy design. In fact, it was known and used in Japan for various types of polearms (nagamaki and nodachi as well).

Their purpose was to hook the enemy weapon as well as protect the hand too.

A Japanese "crossguard" on a yari. Putting such guard on a katana or a tachi wouldn't have been impossible if they deemed necessary to protect the hand.

The Japanese of the period would have put such devices (called hadome in Japanese) on their swords if they wanted to do so or if various hands injuries would have occurred during the long period of usage of these blades, and we would have seen them in the foreign adaptations of the katana as well (more on this later).

Morever, Japanese artisans of the 17th century were familiar with even more complex guards too! In fact, European style small swords hilt and guards were produced in Japan for the foreign market due to their lacquerware work.

A famous example taken from the Met museum of a European sword fitted with a hilt made in Japan, from the 18th century. There are quite a few hilts and handguards made in the same fashion, to testify that the Japanese were aware of such design and know how to replicate them.

So all things considered, it just makes sense that Japanese swords don't need bigger handguards/ crossguards (otherwise, we would have seen them!), which come at some costs: they lower the point of balance so they remove power in the cut (but increase the control of the blade) as well as adding weight and increasing the time needed to deploy the sword (a more complex handguard is just more cumbersome when you have to grab the blade and unsheathed it quickly).

So when one wants to evaluate/compare handguards functionality in sword designs, he has to consider that it's not really about a static comparison, but there are some tradeoffs to take into account and that no sword should be considered without its related technique&usage.

Myth 5: "Japanese swords are too heavy for their length and/or too heavy to be used one handed"

This one is another very famous myth that comes either in that form or in "Japanese swords are too heavy for their weight".

But is that true? Short answer, No.

A Japanese blade usually (not most of them) has a thick spine on the back which allow the blade to be rigid, sturdy and gave it mass behind its cuts: those are important properties that allow the blade to cut well and withstand quite a lot of abuse.

However, not every Japanese blades have this feature. Some of them have some form of distal taper called funbari, especially early swords and nodachi, that allow it to be longer without increasing its mass.

And are those swords really that heavy that they can't be used with one hand? Now there are a lot of data on the "average weight" of said swords, but a lot could change and it's hard to verify them, anyway let's take them for granted.

A two handed katana with a blade in between 68 and 73 cm of length is usually in between 900 g to 1500 g, more or less. The average is usually 1000-1200 grams.

That's roughly the same weight and length of European one handed arming sword, and it's slightly lighter than a European longsword (again, average are concerned so take this with a pinch of salt).

Of course weight is only a part of the whole issue, a katana is better used with two hands because of the way it is balanced (which is not that different on how early European arming sword were balanced!).

But it's totally possible to wield a Japanese sword, be it a Tachi or a Katana, with one hand without having to struggle.

One example is the famous Musashi Koryuu school (niten ichi ryu - 二天一流 ) which dual wield a katana with a shorter wakizashi.

And although it's the most famous one, dual wielding traditions existed before that in Japan.

So it is totally possible to use a Japanese sword with one hand and a shield (as we occasionally see) or with another companion shorter sword.

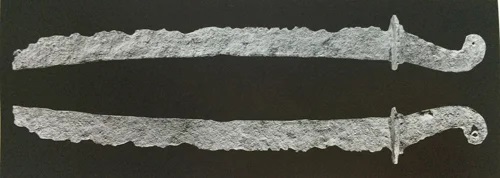

Moreover, in the Chinese adaptation of Japanese katana, said sword was occasionally fitted with one handed handle.

This is also true for a short uchigatana style called katate uchi (片手打ち) which has a shorter handle.

Said sword had a shorter handle but a blade of smiliar length of the ones usually associated with katana, hence at least 60 cm of length.

So it is totally possible to use a Japanese sword with one hand and a shield (as we occasionally see) or with another companion shorter sword.

Moreover, in the Chinese adaptation of Japanese katana, said sword was occasionally fitted with one handed handle.

This is also true for a short uchigatana style called katate uchi (片手打ち) which has a shorter handle.

Said sword had a shorter handle but a blade of smiliar length of the ones usually associated with katana, hence at least 60 cm of length.

They are definitely not too heavy (read as very unbalanced andunwieldy) both for a one hand or two handed sword.

A katate uchi sword; notice the one handed handle. The blade length is definitely on the short side of katana's length.

Moreover, they are not "unbalanced"; they are meant to blade-heavy.

It's definitely not as top heavy as an axe or as a mace, but they usually are not as nimble as a rapier for example. The advantage of this is having very powerful and hard to stop cuts, which is coherent with the 17th century analysis of Marcelli.

In fact it's a common feature of cut oriented swords and it's not unique to Japanese swords either!

So for the first part, this is all. I hope that you have enjoyed this reading! Please feel free to leave a comment and share the article if you liked it!

Part 2 is now available here.

I admit, I always thought it odd when people who have no expertise on Japanese swords and whatnot, having a European/Modern (maybe) point of view that they have the right answer. In the age of google, there should be no excuse for such ignorance despite sources not translated and a few searches away. There's enough to prove what these people are saying yet people get called names by these guys as if they're scared of something. Oh well, glad you're doing something good for betterment of everyone.

ReplyDeleteThank you for leaving a comment!

DeleteI agree, those are information that nowadays are easy to found, but I do think that most of the people who actually spread those misinformation just want to downplay Japanese swords ( and to be honest, I can understand that: a lot of people have claimed that said swords were the best swords ever produced, and this can lead to backlash effect like this one).

But yeah my main goal with this article was to correct a little bit the opinion on the internet about Japanese swords.

"Disprove" My bad.

DeleteIt was time someone made an article like this, and what better person than you? It's so unfortunate that people like to kick Japanese swords down so much. Many people seem to act like a curvature on a sword has absolutely no benefits and a single-edged sword is in every way inferior to a dual-edged one. Thank you again for your fantastic articles!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much!

DeleteI can understand that Japanese swords have been glorified as if they were the best swords ever created, but this doesn't mean that we should accept the downplayed version if that is based on false information; they were not amazing swords in every possible way, but they weren't either that terrible.

One of my main concern was indeed addressing the curvature of the blade. I remember watching a you tube video of Shad were he demonstrated that "your average katana curvature" didn't increase the % of cutting edge into a target, which is what curved swords do... and I can see why, because in his demo, he didn't considered the monouchi, which is the area of the sword were you are supposed to cut and the curvature is at is apex, but take a zone below that!

Only fools would think that any type of sword would be the "best created". To "be the best" would be to say being the most effective design for its application, which is already inherently different due to different styles of sword fighting. Idiots who say longswords are the best clearly have not heard of the oakeshott typology, which just shows how many different weapons with different handling properties fall into the category of "longsword", a category which was not even clearly defined when these tools were actually used, and not just as a weapon class in video games.

DeleteScholargladiatoria also mentions that high quality of Japanese blades were recognized by Europeans and exported overseas.

Very true! I always find those comparisons pointless. Swords are tools and tools have different usage, purposes and quality connected to them. Moreover as they are tools, they are always related to the skill of the user as far as the performance is concerned.

DeleteThe biggest problem, I think, is that we throw everything into the same lot by calling then "swords", when truly there is enough distinction between every type of sword that we could consider them different instruments for a similar job.

Delete@Kazanshin very true! "Generalization" and "over simplification" can always lead to bad conclusions in this context

DeleteAmazing article!!!!

ReplyDeleteSo glad seeing you writing this article!

ReplyDeleteI think a slightly curved sword also helps with quick drawing?

Thank you! I had a lot of fun doing the research related to this and I think it was needed.

DeleteThe curvature might indeed create an advantage for the quick draw but it is still debated. Probably it does but there are multiple opinions on this.

Maybe it's not very obvious on shorter swords, but I strongly believe the advantage of slight curve after seeing some Tenshinryu guy doing battojutsu using a odachi.

DeleteI see that too, they were using a 3 shaku sword and were still able to do battojutsu with that. There are also historical depiction of sword of that size used in civilian context. But those guys of Tenshinryu are indeed impressive!

DeleteDrawing from my HEMA and battoujutsu experience, I would say that no, the curvature in swords doesn't give any noticeable advantage to quick drawing at all. I've been able to apply my battoujutsu techniques to a European longsword thrust into a kaku-obi with a blade length of 38 inches with minimal changes fairly easily (I'm about 5ft 9inches tall so my arm length shouldn't be too above average). The basic principles of a good quick draw are the same regardless of curve: don't hyper-extend your arm and use good saya-biki to do most of the work for you. What does make a sword good for quick-drawing are shorter blades, lighter weights, and wearing the sword in a fashion so that the scabbard can move around easily and freely.

DeleteI know that it's highly debated, but in theory, drawing and cutting from the scabbard could be facilitated by a curvature because the curve of the sword closely follows the curve of the body. A sword with a straight blade have to be drawn in a line tangential to the curves of the body, making the draw slower. I mean it might not be true at all but still it would be interest to see some comparison measured in time.

DeleteBut it' true, shorter and easy to carry/have-access-to swords are generally more faster and easier to draw.

Hi again!

DeleteJust wanted to add a random insight I have recently came to regarding quick-drawing/battoujutsu now that I have an odachi-like sword (a changdao/miao dao which is similar to an odachi) of comparable length to the longsword I have:

One major advantage a katana-like sword has over longswords is the fact they are single edged. When I do battou with my longsword, some draws don't feel safe or comfortable using it since it is very possible to slice or cut the hand holding the scabbard when doing the drawing/sheathing (particularly sheathing/noto) and I feel I have to be more careful when doing these techniques to the point I often have to look down at my hands and be very delicate during the sheathing process. With a single-edge sword I feel quite a bit safer since the edge is only on one side and it's easier to be mindful of where the blade is facing via feeling since you can contact the spine and move it across your hand with minimal fear of injury.

Now, granted it is still possible to flub your sheathing or drawing and cut your hand even with a single-edged sword (happened quite a few times at my old kenjutsu dojo), but I feel particularly unsafe doing that with a double-edged sword since I can only use the flat of the blade to act as a tactile reference point and the sword's edges are dangerously close to my hand or even lying parallel on the skin of my hand if I'm using that as a reference.

To feel safe doing a quick draw with a double-edged sword, I get the feeling I would either have to a) make the tip of the sword dull which could make sense in a European context since some longsword types are extremely pointy at the tip and have little to no cutting capacity at all, b) change my technique to rely less on touch and look down during the re-sheathing process which works but does make you temporarily vulnerable, or c) wear some sort of hand armor or at least a glove to prevent hand cuts.

Thank you for sharing your insights!

DeleteI can totally see your points. Having two edges might screw the flow of the drawing motion or even worse induce self injuries. People with no experience probably will overlook this part, but as far as iaijutsu is concerned, the technique involving the holding and maneuvering of the scabbard is equally important as the one that draw the sword from it.

You are back!!!

ReplyDeleteHope everything went smoothly!

Hope one day you will talk more about the different types of Yari!

Yes I'm back, and I'm very glad to be here again ;) everything was fine, thank you, although I still miss few things here and there that I will set up asap.

DeleteI should definitely write an article about yari!! I've been working in trying to define a new "classification" related to usage for the various types of spear blades because I wasn't really satisfied with the one commonly used but it's very complicated, so I might leave that and just try to describe said weapons without a fancy and organized typology!

Welcome back.

ReplyDeleteI have seen Myth 1,2 and 5, but I never heard Myth 3 and 4.

From what I heard, the Japanese sword is actually longer before the Sengoku Period, then become shorter with blade length around 60 cm and then it became longer again with blade length of 75 cm. Why is that?

Did the Japanese ever use straight double edged sword again in later period after the Asuka Period?

What is interesting is that some myth like katana cutting ability seems to be mentioned outside Japan by European. I remember an account of Japanese sword being able to cut a cloth just by being dropped into the sword edge.

I've tried to see which were the most common myth used, but to be fair some of them are way more popular than others.

DeleteAlso when considering Japanese sword lenght, I think that there is a massive confusion when it comes to the idea of the length being reduced during the momoyama period (I will address this in my next session). To put it simply, during this period we start to see massive armies composed by Ashigaru whom were issues with this type of short sword,easy to deploy and ideal for the close space of pike formation. It was indeed the same style of sword previously worn by the upperclass together with a tachi, the so called "uchigatana". So while the majority of swords was indeed within that length, it doesn't mean that the Samurai stopped using longer sword. There are emakimono of the 16th century depicting street brawl and we see bushi carrying 3 or more feet long tachi (which are indeed nodachi in this case). After that the katana became a status symbol and it's lenght was regulated as you might already know.

Also afaik, ken swords were mainly ceremonial after that period so they weren't used anymore. I can't say why, and I don't think there is a specific reason other than a culture and preference.

I'm aware of that source, iirc it was documented in Italy (or Spain, not sure) during the famous trip of Hasekura Tsunenaga during the late 16th century.

When the British East India Company opened a trade center in Japan in 1613 and tried shipping in some ingots, they got nowhere. Here is a mournful excerpt from the Company's yearend trade summary for 1615: "Coromandel Steel was in no esteem; some which came in on the Hoseander (a ship) being considered inferior to Japan iron. English iron would sell still worse, the best Japan iron being but 20 mace the picul." That is, ten shillings for 125 pounds.

DeleteNotes:

Coromandel = coromandel coast in southeastern india

They/british east india company started trading in masulipatnam in 1611 and established a factory in 1616.

Coromandel steel = wootz steel.

The thing Japan manufactured most of was weapons. For two hundred years she had been the world's leading exporter of arms. The whole Far East used Japanese equipment. In 1483 admittedly an exceptional year, 67.000 swords were shipped to China alone. A hundred and fourteen years later, a visiting Italian merchant named Francesco Carletti noted a brisk export trade in "weapons of all kinds, both offensive and defensive, of which this country has. I suppose, a more abundant supply than any other country in the world." Even as late as 1614, a single trading vessel from the small port of Hirado sailed to Siam with the following principal items of cargo: fifteen suits of export armor at four and a half taels the suit, eighteen short swords at half a tael each, twenty eight short swords at a fifth of a tael, ten guns at four taels, ten guns at three taels, and fifteen guns at two and a half taels.

These were top-quality weapons, too. Especially the swords. A Japanese sword blade is about the sharpest thing there is. It is designed to cut through tempered steel, and it can. Tolerably thick nails don't even make an interesting challenge. In the 1560s one of the jesuit fathers visited a particularly militant Buddhist temple - Ishiyama Hongan-ji , at Ishiyama. He had expected to find the monks all wearing swords, but he had not expected to find the swords quite so formidable. They could cut through armor, he reported "as easily as a sharp knife cuts a tender rump." Another early observer, the Dutchman Arnold Montanus, wrote that "Their falchions or scimitars are so well wrought, and excellently temper'd, that they will cut our European blades asunder, like Flags or Rushes..."

Europeans would have come across Japanese swords and purchased (documented) them numerous times in East Asia and Southeast Asia:

Deletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Native_Warrior.jpg

a 16th-century warrior with Japanese swords and armor, possibly a wokou mercenary in southeast Asian territories.

Source: Boxer Codex

"they are far superior to the Spanish blades so celebrated in Europe. A tolerably thick nail is easily cut in two without any damage to the edge"

By Carl Peter Thunberg ( a 18th-century swede), formerly PHYSICIAN to the Dutch Factory in Japan

Those are indeed awesome details!

DeleteI was partially aware of some of them (in fact one of the next myth would address the idea of "Japanese swords being only used in Japan against no or little armor"). It is true that Japanese weapons were exported and prized all over Asia, we can in fact find them in Vietnam, Korea, China and many other SEA countries. Moreover, Japanese mercenaries were hired by the Europeans and this topic deserve an article on its own.

But I have to say that there are indeed some exagerations. Especially in the 19th and 20th century, when Japan was opened to the world, there was a massive "infatuation" with this romantic idea of the Samurai and their swords in the West. That's arguably where the "Katana fandom" begins (as you quoted from your sources people claiming that a Japanese sword could cut through armor and tempered steel... enough to say that is not feasible :'D).

Thank you so much for sharing, those are valuable information!

The Japanese themselves were more numerous than Europeans in Southeast Asia. For example, Following the death of King Songtham, the throne was seized by Prasat Thong in a violent coup. As part of this scheme, Prasat Thong arranged for the head of the Nihonmachi, Yamada Nagamasa, who also served in prominent roles in court and the head of a contingent of royal Japanese bodyguards, to be killed. Fearing retribution from the Japanese community, the new king burnt down the Nihonmachi, expelling or killing most of the residents. Many Japanese fled to Cambodia, and a number returned several years later having been granted amnesty by the king:

Deletethe japanese community of ayutthaya, look at their flag:

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-OrkQ6P04w-w/WJ76GOkm4gI/AAAAAAAARtk/0r8yWvK_emI3CSSMYosDPLC4qbuCvPnSQCK4B/s1600/bed69df4e97f804b7b4e4d7f85cc45

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/24/ba/de/24bade418aa578564bf4be4712ea89d8.jpg

japanese merchants:

https://www.kyuhaku.jp/exhibition/img/s_47/p14.jpg

japanese trading ship in the 17th-century vietnam:

https://www.michaelmossbooks.com/uploads/article/2019/03/17/thuong-diem-cua-cac-nuoc-phuong-tay-o-dai-viet-the-ky-xvii-38959869.jpg

@ henrique

DeleteCome now . I've always hated the katana bashing hype, but this is ridiculous. Lets think of this logically. European armor, with its tempered steel, were strong enough to withstand musket fire. Even if we generously assume, (and NO, that assumptions is still bs), that a sword could cut through 2 inches of solid steel, no human would have the strength to do it. No matter how sharp, that katana still has an, on average, an inch thick spine that would have to be driven through solid steel for a considerable length in order to 'cut' armor

The modern soldier wears camouflage gear made from fabrics, which unquestionably provides less protection then full plate. Even bullet proof kevlar only protect the front and back of the torso, and is only used as protection against side arms. Why is that? because no bodily armor today can protect you against a 5.56×45mm NATO round of a M4 Carbine.

Had the katana been so effective at bypassing armor, logic dictates that the Japanese would not have invested so much resources in refining their armor, which would be a waste of resources.

Finally, a simple test of logic that rebuts this assertion. What happens when 2 japanese blades clash? Since, as you claim, they are capable of cutting through a far thicker sheet of metal, do they simply slice each other off? but then one must retain its form to slice the other, so how would that work?

I don't claim anything, dead people claim, my original comment is all about when the WESTERN fandom started. It is all written by dead european people starting as early as the 16th century. When you look at the history of katana: There is fandom from both other ASIAN countries and Western countries in old documents . According to Chinese sources, Lan Yu (died 1393) owned 10,000 Katana, Hongwu Emperor was displeased with the general's links with Kyoto and more than 15,000 people were implicated for alleged treason and executed. Japanese swords became cherished objects of the Siamese royalty and were kept as part of their indispensable regalia. As late as 1614, a single japanese trading vessel from the small port of Hirado sailed to Siam with 46 swords.

Deletehttp://dharesearch.bowditch.us/smithsonian/E101(a).jpg

a daab that was presented to President Franklin Pierce (President 1853-1857) by King Mongkut (Rama IV) of Siam.

@henrique the story of Yamada Nagamasa is amazing, and it's indeed a proof on how active Japanese were outside their country. Beside Woku raids of the 16th century, a lot of Japanese fought on Cambodia, Siam and even minor Island in Indonesia.

Delete@Armchairskeptic Indeed, as henrique said, he was just quoting a western source on the katana. Although we often blame popculture for the glorification of said sword, it was a much more older phenomenon.

Pretty much it has been overhyped since the 18th and 19th century, and I still don't know why (although I suspect the isolation and the sudden "re-discovery" of the country played a massive role)

@henrique

DeleteOh now I get what you mean.

@Gunsen History

I guess exotic mysterious stuff is always more interesting (and profitable) than familiar items back at home?

Either way, that is proof that the Japanese swords did earn a reputation of being good quality blades!

It is worth remembering to also double check sources and preferrably with someone with the knowledge of native language. It is quite possible European researchers were exagereting a lot since it is practically impossible from the physical point of view to cut even mildly good blade even with the best blade ever. Or cut a plate. I'm not bashing on Japanese blades, they are definetely great weapons, but a sword is just a sword, it won't mystically cut through other weapons unless they are of terrible quality.

DeleteMany writers tend to exagerate their experience with something, especially if they are not familiar with the subject. During 1656-1658 Swedish-Russian war some Swedish commander, while describing, one of engagements between his troops and Russian cavalry detachment noting enemy ferocity in melee combat and advised to avoid it as much as possible. Curious thing is that Russian sources which talk the skirmish mention no instance of melee at all, stating that cavalrymen engaged in a short-lived shootout. Checking sources "from the other side" (Japanese in this case) is usually preferable.

Love the article BTW.

Thank you @Dmitry!

DeleteYou are correct, but I think that the point henrique wanted to make is that the so called "katana fandom" was indeed born through the exaggerated claims of Western sources in the 20th and 19th century.

We do see mythical properties applied to swords (like cutting through armor) both in Japanese accounts and inside European depictions, it was fairly common actually. But we have to apply rigorous logic and physic to understand that a claim is often made to overstate something and should be taken as "entertainment" effect rather than pure truth.

Yeah, exagerating is nothing extraordinary for people from any side, so I can totally see such incredible details being written here and there. I remember reading a book on Roman warfare which cited some ancient author describing Roman gladius being able to cut both elephant tusks in a single strike without stopping. Now that gives plasma-forged fantasy katanas run for their money.

DeleteI find it strange that European claim of Asian weapon and metal superiority seems present even in Roman times.

DeleteI remember a quote from a Roman author that the iron from Seres is the best the Roman know, the Parthian second.

Seres is implied to be China or Central Asia.

Japanese swords though seems to have a different status in this, in that not only European spoke of its sharpness and quality, but also the Chinese. I mean the Chinese general Yu Dayou said that Portuguese sword is soft and that they are not big threat, while he speaks highly of the fighting quality of the Wokou.

Another peculiar Japanese thing that is less spoken in my opinion is the Iai sword draw attack that is probably unfamiliar to a European. There is a quote from a European reverend about the sword draw, in that someone could be caught offguard as they thought that they are in a safe distance.

Also a sheathed sword is deceptive in that the real length of the sword is unknown both from the way the blade is covered and the way the sheath is held.

Gunsen, how often is such drawing sword attack used in combat or is it just Edo Period thing?

@Joshua

DeleteThat's true but I think you can find similar praises in Eastern sources in regard to Western swords - I remember reading Middle-east sources of the period praising the high quality of the Frankish swords.

Also if a sword it's praised by so many people historically, there is no reason to believe that said weapon wasn't regarded as a good weapon and that we shouldn't do it nowadays.

To your question, the origin of the katateuchi and the uchigatana itself was to have a weapon easy to carry, easy to to draw with one quick motion and easy to deploy/use both in and outside the battlefield, especially for Ashigaru. That's the whole reason why the katana has usually a moderate lenght and it's carried that way. In fact, it is very likely that this techniques originated from the battlefield and daily life of the 15th and 16th century so it's definitely pre Edo although it was an art defined and polished during those 200 years of peace.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Delete"they are far superior to the Spanish blades so celebrated in Europe. A tolerably thick nail is easily cut in two without any damage to the edge" By Carl Peter Thunberg ( a 18th-century swede)"

DeleteThis is an eye opening quote, where can I find the source for it though?

@Henrique

DeleteIn the 1560s one of the jesuit fathers visited a particularly militant Buddhist temple - Ishiyama Hongan-ji , at Ishiyama. He had expected to find the monks all wearing swords, but he had not expected to find the swords quite so formidable. They could cut through armor, he reported "as easily as a sharp knife cuts a tender rump." Another early observer, the Dutchman Arnold Montanus, wrote that "Their falchions or scimitars are so well wrought, and excellently temper'd, that they will cut our European blades asunder, like Flags or Rushes..."

Is there a book I can find this quote in?

Excellent article, was looking forward to this one and am definitely looking forward to the next! I recently actually had a discussion with somebody on the whole "the curve of a Japanese sword isn't sufficient on average to be of benefit to the cut/there's no such thing as a 'draw cut' sword because the motion to cut is the same no matter what sword you're using" thing. I'd always insisted that curved swords were technique reliant in the cut; it's good to see some more info on that point!

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteI know, the "shallow curvature with no benefits" is indeed one of the most common myth that gets repeated over time. However here you can find pretty much all the benefits that said shallow curvature can give you; moreover, we should start to acknowledge that there isn't an "average/standard curvature" on Japanese swords, they changed through history.

To add a small thought bubble.

ReplyDeleteMyth busting...

Well, simple fact is that for most people somethat(not scholars and not natives) educated on the matter, topic of this post is one hell of a vague topic.

For example, we compare "japanese swords"/"katanas". What is Katana? Which one?

Many if not most viewers of this blog will readily imagine 12th,13th,14th,15th and 16th century knights, quite probably - much more precisely than just that.

Eastern(pr, to be even more precise - all non-central/western European) societies are one huge mess.

Yes, many english speaking enthusiasts will be able to distinguish 15th and 16th century samurai, but how many of them will be able to tell the difference the way they'd be able to describe development of italian white armor of the similar timeframe? Or with, dunno, Ming chinese?

And these are comparatively known and well-understood examples with large modern countries and pools of researchers backing them!

This returns us to where we have begun:

While i definetely like your post, i none the less would like to sugest adding, well, context(ha-ha) and timeframe.

Not just good/bad katana, but, say, 15th century types, in context of a typical 15th century japanese armor and style of warfare. Contemprorary not to some vague "knight"(10...17 century), but to a much more specific type of man-at-arms of, for example, from the war of the roses, or i don't know, Ottoman conquest of Hungary. And not to arming sword per se, but a date-to-date, type-to-type, warfare-to-warfare comparission.

Non-western cultures need to be brought out of this timeless good/bad "oriental curiosity" type of discussion...

Sir you are extremely correct.

DeleteTo be honest, I was a wondering which kind of article I wanted to write for this topic. On this blog, I usually try to write as many details about tactics, arms and armors as I can, and as you noted, this article lack said feature in the sense that I'm addressing the whole "nihontō" category without a context of reference (time period, types of swords, design and so on).

You are right and for me it wasn't a straight forward choice, but I decided to deal with this topic like this (using for example interchangeably the word katana and Japanese swords, which is not entirely correct to be fair) for a couple of reasons.

The first one is that I wanted to write an easy to read piece (and I'm not sure I managed to do that since it is way longer than I expected) that addressed the topic as it is usually addressed ( with a super wide general and a-historical context, I would say). This is because many people are familiar with this type of frame and while this blog is essentially aimed for people who want to get more details, this page might be a good starting point for people that are simply curious but don't want to spend too much time on a very specific topic. So it's really a "pop"-article that belongs to my "ramblings" category, aimed for a much wide an general public.

The second is because I'm planning to fill this article with links to my others, much more detailed articles. In the future I will write specifically about the swords of the 12th, 13th,16th centuries and so on, and I will try to be as detailed as possible.

You can already see in "myth 1" that while I argue that Japanese steel is highly misunderstood, I have an entire detailed series of articles that deal with the topic of smelting and forging. Having such details here would have been too long, and maybe a little bit boring for those who don't want to dive into the subject now.

The third is because that's actually a myth I want to discuss in the next part - the fact that Japanese swords are not one single easy thing to define. I have been doing that mistake here, for the sake of simplicity ( mainly because many myths are essentially applied to the entire nihontō category) and because most people are used to deal with the topic like this, unfortunately.

I hope that these reasons might give you an insight on what I was planning to do here with this page, a good and user-friendly starting point to get involved in much more detailed and deep discussions about Japanese arms and armor. I'm quite sure that most people who have actual knowledge on this will find this article "boring" or at least very familiar, and that's ok because it's supposed to be "easy" level :D.

But I wanted nevertheless to release something like this to get more people as possible. Anyway your feedback was very much appreciated and useful, thank you!

Speaking as a currently practicing HEMAist and former kenjutsu/iaijutsu practitioner, you have voiced here something that has been silently driving me insane whenever I talk with HEMAists and I can't wait to see what you have next since this is all a massive headache-inducing semantic mess that really is difficult to clean up now due to the loaning of the word "katana" into English and as a distinct sword classification. I'm sick of how my new martial comrades often conflate "the katana" with all Japanese swords or conversely use the term "katana" as a very limited strawman term that is ALWAYS shorter and has very specific features that make it innately inferior the European longsword when in actuality any comparison with the "刀" in a Japanese context is a meaningless one and the word can mean anything to from a large sword to a kitchen knife!

DeleteP.S. Just wanted to add a bit of knowledge from my old kenjutsu experience and some personal historical digging here:

From what I understand, in the Japanese martial arts manuals and koryu vocabulary that I'm familiar with (I used to practice Yagyu Shinkage Ryu kenjutsu and am familiar with certain documents related to that style like the 兵法家伝書/Heiho Kadensho and the e-mokuroku kept by the Yagyu family, but it also seems this vocabulary is shared in other koryu like the Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu) the term most commonly used to describe the longsword-like weapon that we are learning techniques for in the manuals is 太刀/tachi which (even though they are using the same characters) should not be confused with the term used by some modern nihonto collectors to describe swords put into edge-down mounts in contrast to katana/刀 a.k.a. uchigatana/打刀 which are mounted edge-up through an obi because the context is different. When I do a set of kata like the sangaku/三学 or something, it is described orally and in the documents as sangaku en no tachi/三学圓之太刀 i.e. "the three teachings of the tachi" even though I may be using a so-called katana/uchigatana for the kata. In the historical martial manual context, the best translation for the term is "longsword" with no necessary indication of length, mounting style, or anything else. Unfortunately because of how certain articles classify swords e.g. Wikipedia's articles on katana, Metatron's video on Japanese sword terms, etc., the term tachi in online sword discussions has taken on a completely different meaning than to what it is historically and is often treated as a completely separate entity from katana/uchigatana with people thinking tachi are longer, have more curvature, etc. when in actuality that isn't necessarily true since the word is vague and must be taken in context and can be used to describe so-called uchigatana under the right circumstances. In addition, in the koryu vocabulary I'm familiar with, I have NEVER seen the term uchigatana/打刀 used to describe any type of sword ever and I'm very curious about from what historical source that term came from or whether that's a modern made-up classification. The closest term I could find is the term uchitachi/打太刀 but that's a term used to describe the attacker's role in the kata, not a sword type! X(

What's unfortunate is that standardization of sword vocabulary and sword classification in general is really poor, and moreso with Japanese swords which can lead to insane semantic headaches like "the katana" being called a 太刀/tachi in the manuals but then the 太刀/tachi is a type of 刀/katana in general Japanese! Anyway, best of luck to you in fixing this mess!

It's insanely complicated, to say the least.

DeleteWhy? Because we have at least 3 types of Japanese swords nomenclature going around.

One is based on period sources and it was the original one: just like in medieval Europe people called an "arming sword" just "sword", we have a similar situation in Japan. This of course changed through the periods, and since I will address this in my next part I won't spend too much in this comment (it would be too long), but one instance of this is the word tachi as you said (which can also take into account chokuto sword - but they have different kanji at least). It's not a system, it's just a very broad and confused terminology that people used to refer to swords.

Then we have Edo period nomenclature and modern period collectors nomenclature which is somewhat based on the Edo one. Here we have a strict classification of lenght, mountings, periods and so on. This is the mainstream ones in books on the topic and is usually good for reference but can lead to misleading conclusion when it is used to approach pre Edo period sources.

And finally there is the pop-culture/mainstream nomenclature in which everything is simplified as "Japanese sword=katana" and anything is essentially a "variation of the same sword". That's not official but usually is used a lot by people who don't really have experience and/or are tired of trying to understand the difference between tachi and katana.

Trying to make some order or at least explaining the situation would be very hard, but I will try my best!

Thank you so much for the support, the insights and all the comments!

Love this article and I can't wait to see what's next! Great job! :)

ReplyDeleteAs a HEMA practitioner who used to do kenjutsu, I want to add some insights into the handguard debate.

I think the HEMA community has oversold the belief that the longswords crossguard has better protection than the disc guard. In fact, I now believe the opposite is actually true: disc guards protect the hand better than crossguards. Think about it like this; if you were protecting yourself from arrows which would you rather have to protect yourself?: a long staff or a round shield? Now apply this line of thinking to the crossguard and disc guard respectively.

There is a reason why we HEMAists wear such bulky hand protection when sparring: it's NEEDED. I have been hit on the thumb many many times when sparring and that's without using a "thumbing the blade" grip as shown in some manuals. In addition, I know I'm not alone with this problem since the SPES Heavy gloves that are standard in HEMA longsword protective gear had to update their thumb protection a while back. Plus, many later century longswords, rapiers, and sabers have some form of disk or sidering-like structures to enhance the protection of the hand (sometimes even without a crossguard) which means that even the Europeans thought the lone crossguard was insufficient hand protection. This is still true even for modern HEMA since rapier and saber tournaments noticeable have less hand protection requirements than longsword. That to me shows that there is something wrong with the amount of hand protection on a typical longsword crossguard and there's something missing in the historical context. I think the explanation for why the longsword's crossguard is the way it is may actually be because it was intended to be used in armor with gauntlets which is why the early manuals do often have armored combat sections accompanying them.

Anyway, I also wanted to add some things regarding hand protection on the Asian side of things: it seems that some swords from the Han dynasty did experiment with something like a crossguard:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/31/Han_sword.jpg

In addition, some swords in Japan seemed to have attempted more robust handguard furniture in the Heian period but primarily for decorative purposes:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f8/Metals_and_metal-working_in_old_Japan_%281915%29_%2814780689391%29.jpg

P.S. If you want more info on these swords, check out the discussions I had with 春秋戰國 in the comments of his "Some thoughts on why Chinese never developed complex hilts on their swords " article.

I agree with you; a small discguard is usually not very protective, but in my humble opinion, a large tsuba could protect as much if not slightly better than a regular crossguard.

DeleteOtherwise, we wouldn't have seen rings and other complex stuff added to the regular quillons.

To be fair I think that having a normal crossguard doesn't really provide the advantages a lot of people assume it does in terms of protection. As you pointed out, hits toward the side of the hand can still happen so it's not that protective in comparison to a disc guard.

It's vert interesting to see in fact that Chinese swords occasionally had larger and more protective handguards. A reason to explain why they weren't as common is probably due to the way said swords are supposed to be used - I don't think that there was such a need for complex hand protection.

In fact, in my opinion, crossguards are very useful and effective in the bindings of two blades rather than at merely protect the hands.

Hi again Gunsen! Just wanted to drop in and add a little something I discovered regarding hand protection on Japanese swords: knucklebows existed on Japanese swords ever since the Kofun period and by all accounts seem to be a style of sword native to Japan. In my previous post, I mentioned Tamamaki no Tachi and found an article and a googlebook mention on them stating that the Tamamaki no Tachi had a predecessor that dated to the Kofun period that is seen depicted in haniwa:

Deletehttps://www.rekihaku.ac.jp/english/outline/publication/ronbun/ronbun2/pdf/050004.pdf

https://books.google.com/books?id=5w6QBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA403&lpg=PA403&dq=tamamaki+no+tachi&source=bl&ots=Z8y8P49wBO&sig=ACfU3U1C6WPaEYZkZCR34yZCjxkMHikBCA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiv9a6Fgo3qAhUSG80KHRiVBfUQ6AEwCnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

Did some digging myself and sure enough, I found a haniwa with a knucklebow sword:

https://heritageofjapan.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/image9.jpg

Just sharing this FYI, and also a bit curious; are you ever going to get around finishing your article on Japanese swords or even make some new articles highlighting "unorthodox" Japanese swords like the Tamamaki no Tachi I mentioned or it's Kofun period predecessor?

Thank you so much for sharing!

DeleteI'm aware of that type of hilt, and I believe that this is the same type of swords depicted with the haniwa. I wouldn't consider it a proper knuckle guard for the simple fact that the guard is fitted with bells and I've seen some replicas in museum (I think I have saved that on pinterest, I just need to find it!) which is not in line with the blade, so it might actually be a ceremonial weapon not intended to be used and the guard not intended to be used functionally.

Moreover, during that time period shields were still somewhat used so I would say that those swords wouldn't benefit that much with that complex guard.

On the other hand, is totally possible that said guard existed and were used. I know that Han dynasty dao also had d shaped guards. Unfortunately despite we have quite a bit of blades from that time period, no knucklebow guard was ever discovered yet

On a side note, I would love to write more but in this period I'm kinda stuck with other projects and with all the stuff that is going on in the world at the moment I had to prioritize other things. But hopefully I will be back as soon as possible with new articles!

DeleteStay safe and take care, thank you for your support!

Is there a rebuttal to brittle Japanese sword in your articles yet?

ReplyDeleteThis German video is sometimes posted in comparison debate. What is your opinion on it? I think the Katana fail because of untempered blade which make it brittle.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVCWGwvctt4&t=3m21s

With subtitle:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OO2uiwpniVA

You mention that Japanese swords are tempered, do you get the fact from a Japanese book?

I also see a lot of quote from Sakakibara Kozan being posted whenever lamellar armor is talked about in comparison to mail.

It says that lamellar armor is prone to bad smell and insects settling inside the armor as it is hard to clean.

Yet, we know that for example Southern Chinese tribes who live in wetter place than Japan use leather lamellar armor. It is also used in Europe as well by the Byzantines and during the Migration Period.

I suspect that Sakakibara Kozan is actually saying what might happen if lamellar armor is not cleansed thoroughly, not that it will easily get that condition.

Pretty accurate photos of what Kamakura period full armor with Haidate look like.

http://carat.sakura.ne.jp/yoroi/gallery/siryou/oyoroi/oyoroi.html

Also I found out what period is this armor from.

http://carat.sakura.ne.jp/yoroi/gallery/siryou/turu2a.jpg

From various data, it is believed to be from early 16th century and supposedly belong to Ohori Tsuruhime.

Hi!

DeleteYes I have spent few words on the edge performance of clay hardened Japanese swords on my article " Iron and Steel techonology in Japanese arms and Armor: Part 3" towards the end, but I'm working on the second part of this mythbusting series and I will spend more words on it.

What can I say about that test is that, first and foremost, is a tv demo with 0 scientific value since the viewer is not allowed to see and check all the variables they had in that specific test.

Then I can actually give you at least 3 reasons on why the Japanese sword performed that badly (like why did they hit towards the middle of the blade rather than with the monouchi, which is the part of the blade you have to use?!) but I think that there is only one thing to say: are swords meant to hit a hardened edge of another sword, fixed to a table, with full force? This is the worst scenario you can actually have in any context, and definitely has 0% probability to happen in real life.

It's like pretending to use a ferrari to do a rally in the country side - of course a ferrari would perform badly, but it is not supposed to do that.

A sword on the other hand is not supposed to cut through another sword.

Also, if we do another test in which a clayhardened sword would very much have an advantage, like cutting 100 mats in a row and see which swords is still sharp, do we have to assume that the European sword is inferior? I don't think so.

Moreover, with proper edge allignment the hardened edge of a Japanese sword (which usually on average is higher in VHP than European swords) should "bite" into a softer material. You can see a "test" done by Jorge Sprave in which the hardened steel actually bite into an iron press and get stuck.

The "test" is funny and not serious but still it gets the point:

https://youtu.be/iH32vsxY4xE

I mean I will address again this, probably even editing a little bit my previous article as well, but clay hardened is way understimated and spring tempered way too overstimated.

A springsteel blade can still take a permanent set and/or break and chip.

A clayhardened blade can still flex to some degree without taking a set; you can clearly see that in this recent slowmotion cuts skallagrim did (towards 2.50):

https://youtu.be/3_nkOnKOkHM

And the edge is way more durable than people think; some other documented test against hard materials:

http://islandblacksmith.ca/process/yaki-ire-clay-tempering/

Also about tempering, not every Japanese sword was tempered after hardening: it depends on the sword quality, the school, the material and so on. Having a softer body allow the edge to be very hard and still be reasonably good at dealing with shocks. However, some schools did temper their blades after quenching - the process is called yaki modoshi or aitori and you can find that on several mainstream sources like "The Craft of the Japanese Sword" by L.Kapp and Y. Yoshihara but also in modern day Japanese blade making processes. Those swords were definitely better; however I will elaborate more in the second part of this article for sure.

About lamellar -

DeleteThe quote of Kozan should be taken into a context of long, prolonged campaign that went through the winter as well. In this scenario, lamellar armor is probably the worst one in terms of maintenance because of how bad the lacings could get and how hard is to clean them.

Also nice picture! Although I would say that they are not very accurate, those haidate look more 16th century rather than the ones used in the previous periods as far as we know.

That armor I know, is usually associated with a female Samurai. Could be wrong, could be true: they are still debating about the nanban armor of Ieyasu, let alone this one. But even if it's dated early 16th century, the construction is quite an older one.

Thank you very much for your reply.

ReplyDeleteI noticed that Katana hardness is quite high in VPH.

This article compare the metallurgy of Japanese katana with Ulfbehrt sword and Damascus Steel.

http://www.tameshigiri.ca/2014/01/21/razor-edged-3-comparing-metallurgy/

It seems Japanese katana is harder than the 2 others.

The hardness used for the Japanese sword is that Edo or Sengoku Period one? That is also the easiest photo I could find when I type Katana hardness.

About Kamakura armor, the Haidate in those photo are unfastened, but from visual I think it is quite close to the one in this scroll. Haidate on the right side

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heiji_Monogatari_Emaki_-_Rokuhara_scroll_part_4.jpg

In the middle:

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/NgldNMPprG8/maxresdefault.jpg

There also other examples in Heiji Monogatari Sanjo, all seems to be lamellar and relatively looser than the Hodo and Kawara Haidate.

I also noticed that the Kamakura Period also have this helmet with cheek guard that look similar to Chalcidian helmet.

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcRo7LJY2mUWiG4_jWfdcogBj_bz_qaLJQzwmcGKjUskuZwiElFA

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcR74rzee-HNsN0EQV01ppbhdZOIBNNX8lAIdrYlO0fAKBbGm1HN

I never see them in use before or after the Kamakura.

Lately, I have been looking at various Japanese castle reconstruction.

While some have their Tenshu keep unlinked with other buildings, others are linked together like in Kumamoto Castle.

http://i.imgur.com/sLAb9H6.jpg

I sometimes think if this paintings are authentic or not because most of them look very impressive. The more I see them, the more I think Krak des Chevalier is the standard in the mind of these builders.

Takamatsu Castle

https://stat.ameba.jp/user_images/20181226/11/katuuya2012/82/76/j/o1080081014327576030.jpg

Hikone Castle

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcT9OpnO1llE4ugmiFfIF7ldQZYaMSysgVXU8A08Z_5ubtGIK3oQ

Also the wooden construction for a building this large is very impressive.

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcQ-x0yXw2w3nSRu00wU-jueu9cdYKaRqY_7t3QEwgOtRfwmtLt3

What was the motivation to develop the tall Tenshu keep? Wouldn't it be a target for cannons?

Yes Japanese swords tend to be hard on the VHP scale, in between 650 and 800 (although some sources claimed 1000 VHP, I've never seen an actual scientific paper discussing such hardness). The problem is that measuring hardness is very expensive and most test that analyzed such swords don't go through the VHP scale unfortunately.

DeleteThat sword as far as I remember was a 14th or 16th century blade, although on average you could expect Edo period swords to be on the high end of the spectrum.

About those haidate, the major point is that we don't really know how they were fastened to the leg and usually they should have 3 or 2 split sections at the bottom, although there isn't much iconography on it.

Those helmets are actually a combination of a happuri and a traditional Japanese headgear used by the nobility, the ori eboshi afaik (I'm pretty sure it's one of the several styles of eboshi). The thing is that we are not sure if the happuri was actually a mask + cervelliere style of helmet which was worn under the headgear, just a mask or just a small metal helmet to cover the head, as we have few evidences that indicates some style of helmet and not just a mask.

To the castle, I've just recently started to digging into the material and it's quite extensive, so I'm not very "fluent" yet, but those castles you are linked are later example of true castle-city complex, which were quite big and extended.

The geographical location as well as the outer defensive perimeters that stretched around all the castle allow the keep to be safe against most bombardments.

It is a common misconception that Japanese castles didn't suffer heavy cannonades, in fact there are quite a lot of examples like the siege of Osaka, the Shimabara rebellion and pretty much a lot of Wajo builted in Korea through the late 16th century: they all faced cannons, either Japanese, European or Chinese and were able to withstand such attack thanks to the curved and sloped stone walls as well as the extensive perimeter that surrounded the main building.

The keep was built like that as a sign of power and to function as a residence for the lord, early Japanese castles were much more different; I'm pretty sure that some keeps were damaged by cannon's fire all things considered, but they weren't really used as a form of defensive structure since most of the men were either fighting in other towers or along the walls.

I once read that the Happuri is abandoned during the Nanbokucho Period, probably because of the adoption of various face armor that was fastened to the chin.

DeleteI have questions on Japanese archery.

Did they use arrow guide like this one?

https://bogen-daumenring.de/en/arrow-guides/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ES__ddb7E74

And did they use footbow?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRWvY8PUPwk

I'm curious because I found that footbow was apparently known in 10th century China.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ES__ddb7E74

About castles, I think this is what pre-Senogku Japanese castles look like.

https://shop.r10s.jp/book/cabinet/6403/9784054066403_7.jpg

https://prtimes.jp/i/2535/1856/resize/d2535-1856-299027-3.jpg

https://shirobito.jp/assets/img/upload/article/2018/07/5b39b4955d9191530508437.jpg

https://i.imgur.com/vmbhePc.jpg

About sword hardness, is there a test on Japanese metallurgy before Sengoku Period?

DeleteHere is the 10th century (900-950) China depiction of foot bow, at the top of the picture.

https://wx1.sinaimg.cn/large/6da0632cgy1g503ctzxk5j226o39skjs.jpg

Do you know about this book?

Art of the Samurai Japanese Arms and Armor 1156-1868

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Art_of_the_Samurai_Japanese_Arms_and_Armor_1156_1868

It is has several interesting point like the Kofun sword from before 6th-7th century is longer, often with total length above 100 cm and blade length of 90 cm, but then it become shorter in the 6th-7th century into 75 cm long blade.

How common is the Odachi for field battle. I once read a quote in Historum that the Ming Emperor during the Imjin War heard from his spy in Japan that the Japanese have 500.000 soldier and have among their equipment 500.000 Odachi, wouldn't that mean that every Japanese soldier would actually use Odachi for battle?

Yes you are right, they disappeared when other forms of face armor started to be produced around the 14th century. They were later on introduced again during the Edo period.

DeleteFor arrow guide, there are some manuals that depuct their usage but they might be imported by Korea. It might be possible that they were used on the shorter composite kagoyumi, but we are quite sure that they were not used with the long yumi.

Also, no mention of foot bow and as far as I can tell you, and is rather obvious in mt opinion; the yumi used like that would be rather inadequate and we know that crossbow-like construction in Japan weren't popular for the reasons I have explained in my crossbow article. But that's an interesting find!

Yes those are yamashiro fortresses, the main type of fortifications used in Japan up until the 1540s-60s. I will write an article on those castles for sure.

There are a couple of microhardness of 16th century swords, they are around 700-800 VHP at the edge. But again modern test have been done with traditional smiths lineage and using tatara furnaces with different type of clay hardening and the result was that the edge hardness was in between 600-800 while it was 200-400 for the body of the sword.

Yes I actually have that book, is a very good one. A reason for the shortening of the blade might be explained by the creation of conscripted army; we have a similar situation in between the 7th century as well as in the 16th century. In the 6th and 7th century you have the creation of the imperial army and the Risturyo system, in which farmers were recruited as infantry. A very similar situation with Ashigaru in the 15th and 16th century.

In this context, a shorter mass produced blade easy to carry and easy to deploy im the formation was a good choice for those soldier, hence why they were issued with this shorter weapon. A similar trend apply for the 16th century armies. It's not that longer blades were not produced anymore, but that the average given the nature of said army would have been a shorter sword.

As far as odachi are concerned, it really depends on what you consider a odachi. The problem is that a 170 cm long weapon is a odachi as well as a 120 cm long one. To have a odachi/nodachi according to Japanese terminology, a blade of 90 cm long is enough. In this sense, we can assume that a lot of warrior carried such weapons, in fact during the Korean invasion there are references of Japanese soldiers having longer swords compared to the Chinese and Korean ones. These were essentially sidearms that could still be carry on your waist, in fact there are koryuu schools that teach you how to quickdraw said blades.

On the other hand, blades longer than that were much more rare especially after the 14th century - I would say not common at all. These were essentially polearms and we know that by the 16th century, yari were the main types of polearms used. Moreover you had better alternatives to the odachi, like nagamaki and naginata, which were actually rare already by the 16th century.

Yesterday I thought I have wasted all the interesting things in Japanese armor, then after a little search, I get a lot of picture of Japanese armor. I hope you like them.

DeleteYou may remember that you once linked a Kofun Keiko replica with sleeves, this is the real find.

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcR9rbnTtN5GRYCIcVlsFmBVhkjPnyadUBqz3U18swzfYIeyGurf

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcTTh70BFQyVxXZ1ZoAIQWX_-pMq5Pt0cjCTRf6FBWKRRKjLYjX_

The Kofun Haniwa wearing lamellar manica come from the Imashirozuka Kofun which is the tomb of an emperor, it may mean that such armor are high class equipment.

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcRA_DxAvtvjgsYyRgHhnaj3Kt-e1twLdOKgdnjMLW5omRZkXvAH

Yayoi Period wooden cuirass and vambrace

http://istorja.ru/uploads/monthly_2016_03/0308-02.jpg.41f8a0042a44fa710055c7103ddcc37b.jpg

http://pds15.egloos.com/pds/201001/28/18/b0058018_4b61737cc7f05.jpg

http://istorja.ru/uploads/monthly_2016_03/dbf8bdeee1625154d1901b92cc82275d.jpg.de7ec82c53db699d485b6cb7543ce4a5.jpg

Yayoi shield

http://inoues.net/club6/moriyama247.jpg

7th century wooden helmet, probably Emishi

https://blogimg.goo.ne.jp/user_image/28/10/d1d39a192c00a1941faae845dbb0f2e6.jpg

Kamakura/Nanbokucho Period Wakibiki, the website says it is from early Kenmu Period, so end of Kamakura Period. The size of the lamellar seems to small to be a Sode and the armor style is pre 15th century.

http://www.kjclub.com/UploadFile/exc_board_14/2009/02/21/123514465291.jpg

15th-16th century Wakibiki in an armor set

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcT0TQSD48sqs7Jh18xssR5JCQ_hv7za1B49iqHSB9-duiq3TBRS

Tengu Somen from Muromachi Period.