Kote (籠手) of the late Heian and late Kamakura period

Kote (籠手) of the late Heian and late Kamakura period

A famous pair of kote of the early 14th century wrongly attributed to Minamoto no Yoshitsune. Despite the late age of the example, this type of kote was the main style of arm armor of the 11th and 13th century. Sadly, this is the oldest type of kote we have.

In this article I would start to explore the various types of arms defenses employed by the Japanese warriors from the late Heian to the late Kamakura period.

To add a little bit of ramblings before getting to the topic, I was thinking for month before writings about limbs armors on how to tie the variations of different styles and their historical evolution, so I decided to talk about these armor pieces within different time periods.

So here we will talk about the armor used to protect arms & hands from the 10th to the late 13th century. This might seems a long period, and indeed different styles of arm armors were used throughout the different wars of the Heain and Kamakura period.

However, I chose this period because these items were usually worn by the mounted warriors of the period rather than by their foot counterpart, and so they had to favour the hard skill of mounted archery.

In fact, I would argue that many of these designs were based on the fact that the main weapon of the Samurai of this rather long period was the bow (and his horse as well); this long form fitting sleeves were introduced first and foremost to keep the bowstring from snagging on the sleeves of the warrior’s under robe, which were usually very large in traditional Japanese fashion of the period. Adding plates to defend the arm on the outside as it faced the possibility of being pierced by arrows was the next logical step.

Moreover, it is important to consider the defense of the upper arm and shoulder in conjuction with the large shoulder-shields of the period, the Ōsode (大袖).

The term kote (籠手) was in use at the latest from the time of the Genpei War and in later times the term was also written with the characters 小手. The kote consisted of sleeves with a teko (手甲), a sewed-on ichi no zaban (一の座盤 ) and ni no zaban (二の座盤) metal plates, an upper plate called kanmuri no ita (冠板) on the top and usually (but not always) mail in between these elements. This is pretty much the general feature of Japanese arms armor.

The main styles of arm armor of the period could be divided into shinogote (篠籠手), tsutsugote (筒籠手), ubugote (産籠手) and namazugote (鯰籠手) which are also known as Yoshitsune kote.

Let's start with Heain period kote, that despite the efforts of Edo period scholar to create a rigorous system of nomenclature and categories, as always with Japanese arms and armors, we have a lot of exceptions.

In fact, we lack any type of archaeological artifacts from the period and we only have extremely few depictions of armors in general when it comes to the entire Heian period, although we still have something towards the 11th and 12th century.

Looking at the Bandainagon ekotoba (伴大納言絵詞) we can see kote which protects the arms up to the back of the hand, but it seems that they don´t feature any zaban, so no plates on the arms.

However, it has been speculated that this kote actually have plates sewn on the inside and hidden under the clothes that envelop the arms, so we can speak of ubugote (産籠手).

The Bandainagon ekotoba. Despite being the main reference for arms and armors of the 12th century in Japan, it is very hard to gain small details such as how kote look like in the period.

From the late Heain period we can also ubugote in the Nenjugyôji emaki and what seems to be identical kote interpretations are also seen in the Kokawaderaengi emaki (粉河寺縁起絵巻) as well as in the Shôgunzukaengi emaki (将軍塚縁起絵巻). So it is assumed that zaban were introduced somewhere from the late Heian to the early Kamakura period ( in the 11th and 12th century).

Not surprisingly, this is what we have for the 11th and 12th century given the low number of depictions that could be used.

It is fair to assume that this kote protected quite well the lower arms and the hand especially from arrows, which were the main threats of the battlefield for mounted archers of the period.

We don't see kote being worn by the foot soldiers in these depictions of the 12th century, and we could immagine that those plates would have not been superb to prevent swords or polearms strikes given the fact that as far as we know they only protected the lower arms. Moreover, these kote didn't protect the inside of the arm, to facilitate archery and most likely because those areas were less exposed to incoming arrows for the Samurai whom wore them.

Moving towards the Kamakura period, we have more depictions to work with and better details.

In this period we have the introduction of the upper zaban as well as the hijigane (肘金), a small circular plate that should at least deaden the impact of blows in the elbow region.

In this context, the Heiji monogatari emaki is one of the best source of information and details on Japanese kote of the period. Although it is dated 13th century, the artwork should depict arms and armors from 12th century.

A scene from the Heiji monogatari emaki depicting various types of kote

It is also very popular and still quite widespread to assume that Japanese warriors of the period only wore one kote on the left arm, in order to facilitate archery.

There is one major issue with this argument, that derives from the fact that Japanese kote were already optimized to facilitate archery! So there was no point in wearing just one although to be fair we do have depictions of what seems to be free of armor right arms. It might be that the right arm kote was covered by the baggy sleeve of the under robe worn under the armor.

Karl Friday states that the elite bushi of the period, more often wore kote on both arms (rather than on the bow arm alone, a practice widespread among less affluent warriors).

Other very usefull depictions of the mid and late Kamakura period (13th century) are to be found in the Moko Shurai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞), the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba (後三年合戦) and the Tsuchigumo Zoshi Emaki (土蜘蛛草紙絵巻).

In this scrolls we could find all the aforementioned styles of kote, but most importantly a step towards higlhy decorated ones and the usage of mails use to connect the plates, which could be seen already by the 13th century.

A close up of the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba showing details of kote armor.

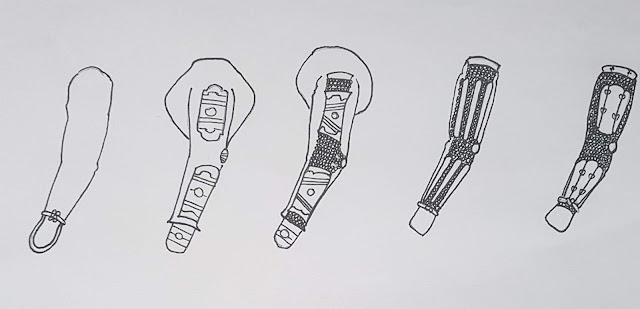

Handsketch done by me for the various styles of kote of the Kamakura period; from left to right, ubu gote, early namazugote, late namazugote, shinogote and tsutsugote.

Details of yoshitsune kote and sode.

Shinogote seems to have been a choice for foot soldiers or less wealthy samurai up until the 14th century, when they started to be adopted by the elites as well given the widespread usage of mail armor. Variations without mail existed as well and in this timeframe the shino gote were usually made of 3 or 4 long and narrow flat plates stichted to the textile frame of the kote, usually linked with mail.

Tsutsugote seems to have emerged quite late as a result of the merging of shino and namazugote design, although evidence of such construction existed well into the 13th century. They differ from later period ones as they only defended the outer arm, while later versions encased the arms a little bit more.

For this article it's all, I hope you enjoyed the reading! Most of the emaki listed here are available online through various platforms and I invite you to check the details through high quality close up of the pictures. I might consider adding more depictions as well in the future, but this article should give you an idea on the style of armor used for the arms of the period.

Thank you so much for your attention, please feel free to ask question and share the article!

A famous pair of kote of the early 14th century wrongly attributed to Minamoto no Yoshitsune. Despite the late age of the example, this type of kote was the main style of arm armor of the 11th and 13th century. Sadly, this is the oldest type of kote we have.

In this article I would start to explore the various types of arms defenses employed by the Japanese warriors from the late Heian to the late Kamakura period.

To add a little bit of ramblings before getting to the topic, I was thinking for month before writings about limbs armors on how to tie the variations of different styles and their historical evolution, so I decided to talk about these armor pieces within different time periods.

So here we will talk about the armor used to protect arms & hands from the 10th to the late 13th century. This might seems a long period, and indeed different styles of arm armors were used throughout the different wars of the Heain and Kamakura period.

However, I chose this period because these items were usually worn by the mounted warriors of the period rather than by their foot counterpart, and so they had to favour the hard skill of mounted archery.

In fact, I would argue that many of these designs were based on the fact that the main weapon of the Samurai of this rather long period was the bow (and his horse as well); this long form fitting sleeves were introduced first and foremost to keep the bowstring from snagging on the sleeves of the warrior’s under robe, which were usually very large in traditional Japanese fashion of the period. Adding plates to defend the arm on the outside as it faced the possibility of being pierced by arrows was the next logical step.

Moreover, it is important to consider the defense of the upper arm and shoulder in conjuction with the large shoulder-shields of the period, the Ōsode (大袖).

The term kote (籠手) was in use at the latest from the time of the Genpei War and in later times the term was also written with the characters 小手. The kote consisted of sleeves with a teko (手甲), a sewed-on ichi no zaban (一の座盤 ) and ni no zaban (二の座盤) metal plates, an upper plate called kanmuri no ita (冠板) on the top and usually (but not always) mail in between these elements. This is pretty much the general feature of Japanese arms armor.

The main styles of arm armor of the period could be divided into shinogote (篠籠手), tsutsugote (筒籠手), ubugote (産籠手) and namazugote (鯰籠手) which are also known as Yoshitsune kote.

Let's start with Heain period kote, that despite the efforts of Edo period scholar to create a rigorous system of nomenclature and categories, as always with Japanese arms and armors, we have a lot of exceptions.

Reconstruction of Heain period kote 11th to 12th century style by Y.Sasama. It is assumed that the plate could have been covered by clothes as well. No upper plates nor mail was used in this period; the defense of the upper region was granted by the Ōsode.

In fact, we lack any type of archaeological artifacts from the period and we only have extremely few depictions of armors in general when it comes to the entire Heian period, although we still have something towards the 11th and 12th century.

Looking at the Bandainagon ekotoba (伴大納言絵詞) we can see kote which protects the arms up to the back of the hand, but it seems that they don´t feature any zaban, so no plates on the arms.

However, it has been speculated that this kote actually have plates sewn on the inside and hidden under the clothes that envelop the arms, so we can speak of ubugote (産籠手).

The Bandainagon ekotoba. Despite being the main reference for arms and armors of the 12th century in Japan, it is very hard to gain small details such as how kote look like in the period.

From the late Heain period we can also ubugote in the Nenjugyôji emaki and what seems to be identical kote interpretations are also seen in the Kokawaderaengi emaki (粉河寺縁起絵巻) as well as in the Shôgunzukaengi emaki (将軍塚縁起絵巻). So it is assumed that zaban were introduced somewhere from the late Heian to the early Kamakura period ( in the 11th and 12th century).

The Shôgunzukaengi emaki; the depiction is rather basic but what can be seen on the arm is likely to be a ubugote.

It is fair to assume that this kote protected quite well the lower arms and the hand especially from arrows, which were the main threats of the battlefield for mounted archers of the period.

We don't see kote being worn by the foot soldiers in these depictions of the 12th century, and we could immagine that those plates would have not been superb to prevent swords or polearms strikes given the fact that as far as we know they only protected the lower arms. Moreover, these kote didn't protect the inside of the arm, to facilitate archery and most likely because those areas were less exposed to incoming arrows for the Samurai whom wore them.

Moving towards the Kamakura period, we have more depictions to work with and better details.

In this period we have the introduction of the upper zaban as well as the hijigane (肘金), a small circular plate that should at least deaden the impact of blows in the elbow region.

In this context, the Heiji monogatari emaki is one of the best source of information and details on Japanese kote of the period. Although it is dated 13th century, the artwork should depict arms and armors from 12th century.

A scene from the Heiji monogatari emaki depicting various types of kote

It is also very popular and still quite widespread to assume that Japanese warriors of the period only wore one kote on the left arm, in order to facilitate archery.

There is one major issue with this argument, that derives from the fact that Japanese kote were already optimized to facilitate archery! So there was no point in wearing just one although to be fair we do have depictions of what seems to be free of armor right arms. It might be that the right arm kote was covered by the baggy sleeve of the under robe worn under the armor.

Karl Friday states that the elite bushi of the period, more often wore kote on both arms (rather than on the bow arm alone, a practice widespread among less affluent warriors).

Other very usefull depictions of the mid and late Kamakura period (13th century) are to be found in the Moko Shurai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞), the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba (後三年合戦) and the Tsuchigumo Zoshi Emaki (土蜘蛛草紙絵巻).

In this scrolls we could find all the aforementioned styles of kote, but most importantly a step towards higlhy decorated ones and the usage of mails use to connect the plates, which could be seen already by the 13th century.

A close up of the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba showing details of kote armor.

In this frame it is possible to see the inner portion of the arm which seems to be covered by mail.

We can also see various types of lacquerware applied to the kote; at this point in history, the Samurai of the period had already established their power and we can see a trend in arms and armors as well, from rather crude and minimalistic to embellished armors with various forms of decorations.

The kote depicted in the Heiji monogatari emaki seem to be black-lacquered whereas those depicted in the Moko Shurai Ekotoba look more as if of kondō, or of a black-lacquer finish with either kondō ornaments or suemon inlay in the form of crests.

Toward the late Kamakura period we also see the development of tsutsugote, probably derived from the shinogote as at this stage seems to be very closely related. It is assumed that the plates in the tsutsu style were hinged together in the same way as suneate (shinguard) of the period were hinged.

The kote depicted in the Heiji monogatari emaki seem to be black-lacquered whereas those depicted in the Moko Shurai Ekotoba look more as if of kondō, or of a black-lacquer finish with either kondō ornaments or suemon inlay in the form of crests.

Toward the late Kamakura period we also see the development of tsutsugote, probably derived from the shinogote as at this stage seems to be very closely related. It is assumed that the plates in the tsutsu style were hinged together in the same way as suneate (shinguard) of the period were hinged.

We also see decorations in the gauntlets of the period which up to this point didn't procted the fingers, again a design choice dictated to allow and facilitate archery.

Black-lacquered tekō with a sukashibori ornamentation in the form of waves, chrysanthemums on a branch and butterflies are also called Yoshitsune-gote (義経籠手).

As such roundish tekō resemble the head of a catfish (namazu, 鯰), the entire kote were also called namazugote (鯰籠手). They were in use up to the Kamakura period and it seems that they formed quasi the default shape of tekō for that era.

Black-lacquered tekō with a sukashibori ornamentation in the form of waves, chrysanthemums on a branch and butterflies are also called Yoshitsune-gote (義経籠手).

As such roundish tekō resemble the head of a catfish (namazu, 鯰), the entire kote were also called namazugote (鯰籠手). They were in use up to the Kamakura period and it seems that they formed quasi the default shape of tekō for that era.

Handsketch done by me for the various styles of kote of the Kamakura period; from left to right, ubu gote, early namazugote, late namazugote, shinogote and tsutsugote.

Ubugote seems to have remained in usage during the early kamakura period, but later disappeared as other styles emerged.

The most popular one for wealthy Samurai from the 12th to the early 14th century seems to have been the namazugote style, which was made of larger plates exposed and highly decorated; later versions also used mail to connect the plates as well.

The most popular one for wealthy Samurai from the 12th to the early 14th century seems to have been the namazugote style, which was made of larger plates exposed and highly decorated; later versions also used mail to connect the plates as well.

Details of yoshitsune kote and sode.

Shinogote seems to have been a choice for foot soldiers or less wealthy samurai up until the 14th century, when they started to be adopted by the elites as well given the widespread usage of mail armor. Variations without mail existed as well and in this timeframe the shino gote were usually made of 3 or 4 long and narrow flat plates stichted to the textile frame of the kote, usually linked with mail.

A 14th/15th century kote very likely to be assembled in the same way of those 13th century ones according to the depictions of the scrolls.

For this article it's all, I hope you enjoyed the reading! Most of the emaki listed here are available online through various platforms and I invite you to check the details through high quality close up of the pictures. I might consider adding more depictions as well in the future, but this article should give you an idea on the style of armor used for the arms of the period.

Thank you so much for your attention, please feel free to ask question and share the article!

Gunbai

Very complete post

ReplyDeleteThanks! I'm glad you liked it

DeleteHa! Nice post!

ReplyDeleteThe Kote is one of the most underrated and misunderstood part of japanese armor. It's nice to see something about it in your blog.

Thank you!

DeleteYes, the original project of this blog was to discuss the historical development of Samurai armor specifically so that's my main field of interest and they're probably the most detailed types of article I could write ;)

Hello I love reading your articles. Very informative and authentic. Could you do a article on o tsuchi or Japanese "polehammer" how it was used and what types etc.

DeleteThank you so much @Hajdar.Delija!

DeleteI might write something about the Otsuchi in the future but keep in mind that this hammer was a tool rather than a weapon; the closest thing to a polehammer is a description of a type of yari used by the Takeda clan that, as far as we can read in the Koyo Gunkan, had a hammer on top, under the spear head.

Otsuchi might have been used in battle to smash gates or other fortifications during sieges, but it wasn't properly a weapon

"Tsutsugote seems to have emerged quite late as a result of the merging of shino and namazugote design, although evidence of such construction existed well into the 13th century. They differ from later period ones as they only defended the outer arm, while later versions encased the arms a little bit more."

ReplyDeleteWhat are later period variant known as?

Also what is the piece on the left? Is it the suneate ? https://www.pinterest.com/pin/210050770109315910/

DeleteI stumbled upon an example of kote where the upper arm had hinged plates similar to the suneate, but I could not find it again. I believe it was a museum piece, although I cannot verify how reliable the source was.

They are still know as tsustugote, but they look more like this:

Deletehttps://i.pinimg.com/564x/00/fe/a1/00fea1dc56a3af02d739114332bd627e.jpg

While Kamakura period ones look like this:

https://i.pinimg.com/564x/7a/57/5f/7a575f33cfa8430d368dcfb13a57d590.jpg

(They cover more the outer-side rather than the sides of the arm as well)

Later ones encased the arm more.

Also yes, that piece is a suneate!

Anyway, the structure you describe is in line to what tsutsugote are, hinged plates that could encase the arm. The hinged system is identical to the ones used in suneate

But even in most later tsutsu kote, it seems to me that the upper arm is covered in small metal lames. What I am refering to is similar to the pocture in your pinterest I cited. In that there are large hinged metal plates protecting the upper arm similar to the fore arm and the suneate.

DeleteOr may be it is I who am mistaken.

Oh I got what you mean; well yes having plates on the upper arm was rare because the sode moved from being standing shield to actual pauldrons that covered that part of the arm; an example of this shift could be expressed by bishamon kote which had sode integrated on the upper arms.

DeleteBut they do exist:

https://i.pinimg.com/564x/24/eb/86/24eb86cd2ac77611cca31b828025a45a.jpg

Yep! The picture I saw was especially armored though. it looked nearly identical to the drawing on the right in your picture. https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-NBs5ZaQoiRI/Xnzh-p81eyI/AAAAAAAABw4/oOF8BMgpYy0_M2kP_Aczqj07tJOCOHj3ACLcBGAsYHQ/s1600/20200326_180447%2B2.jpg

DeleteHello, Gunsen.

ReplyDeleteYour article is very interesting because you are explaining one of the least mentioned Japanese armor piece, I mean the Heian Period Kote, not just any Kote.

Is the forearm plate a derivative of the earlier vambrace?

When did the Japanese change from the Keiko lamellar pauldron + vambrace to Sode + Kote?

Why did they change from such proven armor to cloth sleeves? Why didn't they create clothes with narrow sleeves?

I am very interested in this topic, so I would probably ask a lot.

By the way, I hope you are healthy and safe.

Thank you Joshua, I'm healty and safe and I hope it's the same for you!

DeleteTo your question;

It is assumed that the plate on the forearm is a derivation of the previous periods vambraces.

It's unfortunately quite impossible to answer your other questions; we simply don't know as there are no written descriptions, almost no depictions and no physical evidences of the armor of the 9th,10th and 11th century.

It is assumed that in between the 9th and 10th century the Osode was developed but don't quote me on that, I might be wrong. Sasama has some sketches on some type of intermediate period sode that try to establish a connection between the katayoroi and the Osode but they are highly speculative.

We also don't know why they choose to adopt Osode over the katayoroi (tubular pauldrons) but it might have been a choice adopted in order to minimize weight and maximize protection without shields on horseback while carrying a bow.

Kofun and later periods vambraces are not so different from the upper plates found on kote, but the idea of having a sleeve with sewn plates and no plates on the inside is helpful for archery so that the string doesn't catch armor bits while you shoot.

Sorry for the late reply, my internet is slower now. I'm healthy and safe as well.

ReplyDeleteIs there no evidence of armor from the 9th-11th century? Did all armor just get recycled for new soldiers everytime soldiers die, so they never get buried in tombs? I wonder if they could get armor from those period by digging on battle site of some Heian Period rebellions.

How far back did the earliest O-yoroi date? I remember there is fragments of the supposed oldest O-yoroi stored in a temple.

For the 8th century, did the Nara period lamellar fragment count as evidence?

One of the most interesting thing about this is why did only the Japanese go to this length for mounted archery and why such equipment are never developed in other archery culture.

I found this website with swords from the transitional period from straight to curved sword.

http://www.ksky.ne.jp/~sumie99/kissakimoroha.html

The Tachi in the Kasuga-taisha shrine is very interesting.

Sorry for this late reply as well, this comment went unnoticed unfortunately!

DeleteAs far as I know (but I'm quite confident on that) we do not have evidence of the armor used in those periods; maybe some sparce scale or lamellae but not at the same level of Kofun period findings or later Edo period ones. It was either recycled or simply left to decay over a long time. Unfortunately, Japan climate is quite aggressive on metal and organic materials that stayed in the soil for too long, so it is hard to find something nowadays especially if it was from a battlefield and not from a proper burial.

I believe that the oldest Oyoroi is dated around the 11th century if I recall correctly. Here is the picture:

https://kougetsudo.info/katchu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/eee5a7c181169ffc76613e01efe4f687.jpg

Also yes Nara period scales are indeed material evidence but you can't elaborate a lot from those individual pieces as they are very small. However, the main "gap" is indeed the early Heain period.

I think one of the reason why Japanese armor is somewhat unique is the emphasis on mounted archery with such long bows.

Since the warfare was centered around mounted warfare and heavy arrows, the armor needed to prevent penetration of these closed quarter shot (hence why the boxy shape) and having those huge bows didn't allow the warrior to wield or carry shield like other central Asian culture did with their composite bows. Hence why Osode were developed, to function as shield. But this is just my educated guess to be fair.

Yes, early Heian/late Nara period tachi are very interesting because you can see a gradual shift from the continental design toward a unique Japanese style!

How much do we know about Asuka Period lamellar?

DeleteIf Nara and early Heian Period armor is really unknown, then we don't know when they start lacquering whole lamellar strips then?

Your guess about having to develop the Sode because they use large bows is very logical.

If the oldest O-yoroi appear in the 11th century, did armor like the Keiko still worn side by side with the O-yoroi up to that time?

Th trend I see in Japanese starting from the Warabite-to is for the curve to start at the handle and then as time goes, the curve start moving farther into the blade and then ending around the middle of the blade like in the Katana.

I think such curvature is unique because most curved swords have curvatures in the first half of the blade.

I think that you can make quite a lot of inference from Keiko of the late Kofun period to get a good picture in mind of the armor worn in the early Asuka to mid Asuka period.

DeleteWe do not know exactly when they started to apply the lacquer hardening techniques to lamellar boards, but it is assumed that it was a process developed around the periods of the Oyoroi as you need that kind of technique to create the iconic shape of the armor.

Also as far as we know, Keiko evolved into the Uchikake version and then into the Oyoroi so it could be that you might have some variation across the 8th and 9th century but I would say that around the 10th century the Oyoroi was already consolidated.

Indeed that's the trend I was able to see as well when it comes to early Japanese swords. I know that it has been suggested that those early Tachi were not developed specifically for horseback combat, but applying such a strong curvature at the base of the blade indeed maximize the curvature at the top of the monouchi (the region you have to cut with) at the cost of reducing the overall reach of the weapon: this makes me think that it was optimized for horseback fighting since in that context you will likely cut with the final portion of the blade more often and you won't be hindered a lot by lack of reach given the horse speed.

Is there any reason why the Japanese began to use 2 handed grip with the Tachi?

DeleteIt is quite unusual for cavalry sword to have 2 handed grip.

Interesting question!

DeleteI think it was a combination of the usage of yumi on horseback and how armor develop; since there was no hand shield to use effectively in this context, they optimized the sword to be used with two hand if needed (in case the horsemen had to fight on foot). Although a Tachi can still be used very effectively on one hand given the overall weight and how it is balanced, since it is more nimble than a katana.

Moreover, Tachi were still more used in civilian life rather than on the battlefield, given the bow. So in this scenario, despite having clear cavalry influences, it was an important every day life weapon as well. As in this scenario you won't carry a shield anyway, it might be better to have a two handed long sword. But those are my personal guesses so I might need to check better to see if they hold

The factors that influence early Samurai equipment seems to be barely analyzed.

DeleteThe lacquering of lamellar strips is iconic for Japanese armor, yet we don't know when the practice start. Is the practice was dome because the Japanese know that the lacquering made the O-yoroi to be square and later Do-maru and Haramaki to be tailored in the waist area?

The appearance of the Naginata is also interesting, are there showing of the Naginata being used by mounted Samurai in the Heian and KamakuraPeriod? It seems to be an infantry weapon in the early Samurai period. If it was used against cavalry, was it used to cut horse legs or to thrust? Why did they shift from the Hoko to the Naginata and then back to spear with the Yari?

It is true, it's a shame that we don't have as many information on that period compared to later ones.

DeleteHowever, we do know what lamellar armor from the Kofun period up to the time the practice of tumuli fade out looks like and we start to have evidences of that special lacquered sane ita structure around the 11th century when we have some actual evidence. There is a gap of course but we do have documents regarding armor construction of the Ritsuryoo state ( I remember reading about a specific document that dealt with the time used to make armor and each step; I should have a look and see if sane ita is mentioned) and so we can make some mild inference on that one.

As far as I know naginata on horseback is only shown during the 14th century, not before. it was probably used to cut and thrust against the horses but most likely to hit the rider itself.

They shift to naginata as warfare around that period (after the rise of the Samurai) didn't rely on trained infantry anymore so having a solid and consistent line of men was not possible due to the structure of society and army itself. In this period, it was quite common to have a lot of space to swing your weapon and as such naginata were better. Armor didn't cover as much as later period as well, so while a Hoko was a great weapon for fighting in formation, without formation a glaive type of weapon outperformed it given the armor, tactics and warfare of the period.

Yari became more popular as fighting in formation and bigger armies were introduced; I could elaborate more but I have written this here if you want to have a look ;) :

http://gunbai-militaryhistory.blogspot.com/2018/01/hoko-early-japanese-spears.html

http://gunbai-militaryhistory.blogspot.com/2019/03/naginata-samurais-glaive.html

(If you look it up there should be a pharagraph in both articles were I explained why the hoko wasn't used as much as before and why the naginata after some time was replaced by yari spears).

I remember asking you if blunt arrow head was used in battle for inflicting blunt trauma.

DeleteLately, I had been reading records of native American bows. Their bows were very powerful.

This is the record from The History of Hernando de Soto and Florida.

This is an arrow with stone, hardened wood or cane tip.

"At the same time, the barbarian, having closed his fist, stretched himself, extended and bent his arm to awaken his strength, shot through the coat of mail and basket with so much force that the shot would still easily have pierced a man. Our people, who saw that a coat of mail could not resist an arrow, adjusted two of them to the basket. They gave an arrow to an Indian whom they ordered to shoot, and he pierced both of them."

after the test, the Spaniard considered their mail armor useless.

“they held their coats of mail of no account, which they, in mockery, called Holland cloth. Therefore they made, of thick cloth, doublets four inches thick, which covered the chest and the croup of the horses, and resisted an arrow better than anything else.”

“In the melee, as Soto raised himself in his stirrups to pierce an Indian, he was shot behind. The arrow broke his coat of mail and entered quite deep into his buttock. Nevertheless, for fear that the wound might abate the courage of his men, and elevate that of the barbarians, he concealed the wound that he had received and did not extract the arrow, so that he could not sit down.”

There are other Spanish account like

- finding a human skull pinned by wooden tipped arrow which penetrate a tree halfway

- pierce tree as thick as human thigh

- pierce a man even with blunt wooden shaft

- an archer killed a horse with one arrow

- a cane arrow penetrate into a rider's thigh, saddle, enter the horse and killed it.

They even admit that native American arrows penetrate as deep as crossbows.

“An arrow, where it finds no mail, pierces as deeply as a crossbow ... For the most part when they strike upon mail, they break at the place where they are bound together. Those of cane split and pierce a coat of mail, causing more injury than the other.”

-- "The Gentleman of Elvas”

This one is English account from Jamestown about a native archer shooting arrow through bullet proof shield.

"One of our Gentlemen having a Target [meaning shield in this context] which he trusted in, thinking it would bear out a slight shot, he set it up against a tree, willing one of the Savages to shoot; who took from his back an Arrow of an elle long, drew it strongly in his Bow, shoots the Target a foot throw, or better: which was strange, being that a Pistol could not pierce it. We seeing the force of his Bow, afterwards set him up a steel Target; he shot again, and burst his arrow all to pieces, he presently pulled out another Arrow, and bit it in his teeth, and seemed to be in a great rage, so he went away in great anger."

There was also a quote of a Spanish soldier who held a shield that get hit by 4 arrows at once, the arrows' impact throw him a short distance and make him fall into a river.

Because the depiction of strength and penetration was recorded in a consistent way in both North and South America at different time period, I think they were not embellishment.

It make me think again about the Roman record saying that the Hun use bone tip arrow. I think many "primitive" bows and arrows may not be as weak as I previously thought.

Did the Yumi had similar feats of strength?

Considering that it sometimes strung by several people, I think it should be very powerful.

If a bow is capable of such feat, the design of the O-yoroi would be even more reasonable.

Well, are you sure on the validity of those accounts? I'm not really an expert on native american bows and such but still I would say that those accounts might be pretty much exagerated.

DeleteI can tell you that if you don't have a steel hardened and very fine arrowhead it's hard to bypass mail armor.

Still, the quote about bulletproof shields: good bulletproof armor in that time had to absorb the shock of lead bullets, which tend to "splash" at impact so a softer material is likely to perform better, but it has to be thick nonetheless. Harder steel materials can actually lead to cracking failure so a bullet might be stopped by iron or low carbon steel while it might actually crack and penetrate harder steel. On the other hand, arrows which carry far less energy are not able to crack the steel in the same way, but are very likely to pierce the softer material of the iron. An iron object thus might be "bulletproof" against lead balls but not arrow proof.

This is why Japanese armorer combined the two "alloys", to prevent both weapons.

Anyway I don't think that arrows could be used to deliver "blunt force" shocks. An arrows is a relatively low mass object moving at a relatively low speed, so it doesn't carry a lot of momentum. The strenght of the bow lies in the fact that the surface area of an arrow is very small and so the pressure is high, which leads to penetration and it's arguably much more devastating than bruises or broken bones.

You will definitely feel the impact of an arrow, but it won't be as strong as being hit by other heavier objects like polearms for example.

However I can thell you that the Yumi has similar reputation in the literature of gunkimono (piercing two suits of armor, sinking ships, nailing man and horses in one shot and so on).

Very good article, excellent job as always.

ReplyDeleteGunsen, can you enlighten me a bit whether or not large and well known mercenary groups existed in Japan during 16th or early 17th century? I'm currently organizing Japanese mercenary warband for the En Garde! tabletop skirmish wargame and wonder if they can have some historical basis.

Well I haven't look into that as much as I would have loved to do, but this article might be a great way where to start!

Delete‘Great help from Japan’: The Dutch East India Company’s experiment with Japanese soldiers" by Adam Clulow.

It should be on open access on Jstor!

Thanks, that was a fascinating read.

DeleteYou're welcome! Hope that it was helpful!

DeleteHi Gunsen History, as always and in depth interesting article.

ReplyDeleteDo you have any plans on writing about the usage, technology and ressources?

It would be thrilling to read about similarities (and differences) between the contemporary European and Japanese matchlocks!

Hi and thank you!

DeleteYes it would be very interesting to talk about firearms of Japan in this period, but it's a field that in which I have a rather shallow knowledge so I will need to study more before writing about it. But I will definitely do that in the near future!

Okay, thank you!

DeleteDo you have any sources I could go to for more info about yari vs. armour? Even if it is in Japanese?

Please keep up the good work!

You're welcome!

DeleteI have wrote an article that explain how to defeat late Japanese armor with period weapons and there is a section for the spear. It's very "poor" in the sense that it's not much but if you want to know more about using different weapons against armor I think that anything from "柳生心眼流" and especially their "甲冑兵法" section is very good (they deal with a lot of types of weapons and armors as well, including foot soldier armor). There are some books of the school as well!

Anyway here is my article:

http://gunbai-militaryhistory.blogspot.com/2019/06/defeating-late-japanese-armor-tosei.html

I love your posts on armor making techniques from the past! If your injury was an accident or an unexpected injury while doing what you love, a Personal Injury Settlement Loan

ReplyDeletecan give you the financial support you need while you recover. Rockpoint Legal Funding is the trusted name in quick and dependable legal funding – so you can focus on getting better instead of stressing.