Japanese Sword "Mythbusting" - Part 2 (WIP)

Japanese Sword "Mythbusting" - Part 2

Disclaimer: I accidentally published this article before finishing it, so it is not complete yet. However, since it might required some time and it is mostly done, I think it would be nice to give to everyone a preview of what it would look like. Thank you!

So here we are with the second part of this series where I will discuss other 5 myths regarding the Japanese swords. I strongly suggest you to read my first part, because it has an introduction to give you some "context" to which kind of myths I'm addressing here. Without further ado, let's continue with the myths.

Nagao Totomi no kami Katsukage 長尾遠江守勝景 wielding a sword in full armor; from Koetsu yusho den Takeda-ke nijushi-sho 甲越勇將傳武田家廾四將 by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Disclaimer: I accidentally published this article before finishing it, so it is not complete yet. However, since it might required some time and it is mostly done, I think it would be nice to give to everyone a preview of what it would look like. Thank you!

If you haven't, just to make sure, this is not the average mythbusting in which we will address how swords can't cut through steel, but rather how and why the Japanese swords were historically regarded as high quality weapon.

Myth 6: "Japanese swords are brittle and easy to bend"

This is definitely one of my favorite.

I've read a lot of things about Japanese swords, and one of the most common one is that "how brittle the edge is supposed to be" - so hard that you are supposed to parry with the flat or back of the blade to avoid ruining the edge (spoiler: some proper koryū schools teach that you can parry with the edge).

Now let's address the topic properly: there is a tiny amount of truth into that but as always when it comes to myths, it was over-exaggerated.Some people attribute this idea to the fact that "Japanese steel and iron ores was lousy", but I have already refuted this idea both in part 1 as well as in my dedicated series of Japanese steel technology (here and here).

Another reason that is often brought to highlight the presumed brittleness of Japanese sword is the way they are heat treated.In fact, one of the particular feature of traditional Japanese sword making is the differential hardening - which was found on several other types of blades historically up to the 19th century, both in the East as well as in the West.

What is unique about the Japanese version is the way it was done, the hardness found on some blades and the fact that they stick to it despite knowing other advancement in metallurgy and sword making during the ages.

Said technique “alters the properties of various parts of a steel object differently, producing areas that are harder or softer than others. This creates greater toughness in the parts of the object where it is needed, such as the tang or spine of a sword, but produces greater hardness at the edge or other areas where greater impact resistance, wear resistance, and strength is needed.” The drawback is that the sword won’t behave like a spring, which is one of the main feature of late medieval European swords (but I’ll address this later).

So the edge would be harder, which doesn’t directly translate into brittle. A hard edge would be good against material softer than itself (which happen quite a lot) and good at retaining a sharp edge, but the problem will be that when a strong shock occur, it will chip or break rather than bend or roll: this is how hard steel react to fracture. That’s not a bad thing, because if said shock happen, you cannot avoid edge damage on the sword. It will either chip or roll, and that really depends on how hard the edge is.

A chipped edge from a modern made sword, spring tempered. No matter what material or technique you use, if the edge is put under stress it will eventually be damaged.

The problem is that a crack might be worst than a roll on the short term ( a roll can be easily fixed without losing too much material, but that would still be a weakened part of the sword that eventually will break in the long run), and if the sword is entirely made of a hard material, said crack can actually propagate in the whole blade and shatter the sword in two pieces. This is why you only want the edge with that amount of hardness.

On the other hand, a softer edge will roll more frequently with “less strong shock”, to put it simply. So it’s really a trade off when it comes to edge hardness.

You either want a softer edge that will lose its sharpness faster (due to those microscopic rolled portion here and there) but that would avoid chips or a hard edge that will stay sharp for longer with the risk of chipping in heavy usage. Moreover, a hard edge won’t chip unless it meets something harder than itself (in theory - bad edge alignment can help in damaging the blade as well).

An example of a rolled edge

But what happens if you go with ultrahard steel that compose a good portion of the blade? You have Shintō swords. This is where the idea of katana being fragile came from! This was a problem of Japanese swords of the Edo period. I have already explained the major issue of this type of sword and their flawed design in my article about bladesmaking, but is better to repeat what those swords were.

Some of these "swords" were made with a overly complicated layered structure of different steel, and a very wide and untempered hamon. Due to the edge being too hard (and too hard means around 900-1000 VHP, +100/200 VHP points of the high end distribution of functional Japanese swords, which had a hardness in between 650-800 VHP at the edge) and composing a big portion of the blade, when failure happened, those blades shatters or broke.

Some of these "swords" were made with a overly complicated layered structure of different steel, and a very wide and untempered hamon. Due to the edge being too hard (and too hard means around 900-1000 VHP, +100/200 VHP points of the high end distribution of functional Japanese swords, which had a hardness in between 650-800 VHP at the edge) and composing a big portion of the blade, when failure happened, those blades shatters or broke.

A detail of a Japanese hamon on a sword.

This is where the idea of katana being fragile came from, but it was an oddity rather than a common thing.

Why something like that was done? Because at that point in history, swords were work of art and a wavy and wide hamon was quite valuable as an artistic expression.

Why something like that was done? Because at that point in history, swords were work of art and a wavy and wide hamon was quite valuable as an artistic expression.

What’s interesting is the fact that the smiths of the period were aware of this issue and so they addressed the problem by recreating the functionality and durability of Kotō swords used in the Kamakura and Muromachi period, a movenent called Fukkoto. So shinshinto swords were born, but that’s another story.

Moreover, a very important but at the same time overlooked aspect of traditional Japanese sword making is tempering - the process used to reduce the stress in the steel once the blade was hardened.

Not every sword was tempered, some didn't need that; if the edge was made of relatively medium carbon, you could still allow the hardened edge "merged" (not a very technical term) with a softer body and core, because the edge won't be too hard in the first place.

However, some Japanese blades were indeed tempered - the term used is yaki modoshi (焼き戻し) in order to reduce the stress in the steel and in the matrix of the edge; those swords were highly superior in my opinion.

However, those of mine would be empty words without some fair evidences and testes on differential hardened blades:

Moreover, a very important but at the same time overlooked aspect of traditional Japanese sword making is tempering - the process used to reduce the stress in the steel once the blade was hardened.

Not every sword was tempered, some didn't need that; if the edge was made of relatively medium carbon, you could still allow the hardened edge "merged" (not a very technical term) with a softer body and core, because the edge won't be too hard in the first place.

However, some Japanese blades were indeed tempered - the term used is yaki modoshi (焼き戻し) in order to reduce the stress in the steel and in the matrix of the edge; those swords were highly superior in my opinion.

However, those of mine would be empty words without some fair evidences and testes on differential hardened blades:

Hot rolled 1/8″ x 1/2″ steel bar vs Japanese blade, hardened and temepered. No edge damage. Image taken from here

Hardened 1/2″ logging bridge spike vs yoroidoshi tanto. No edge damage, blade hardened and tempered. Source.

A Nodachi of the 14th century used in battle, against armor and other swords. Minor edge damages, but no deep nicks or cracks as one might expect given the heavy duties the weapon had to face and the overall bad reputation of Japanese edge.

Moreover, the durability of Japanese blades was a major topic of study for later bladesmiths; to test the skill of the artisan and the quality of the blade, they did extensive destruction tests.

One example is the aratameshi. In particular, during the Edo period, an extreme form of blade testing was created in order to discover how much damage the blade could withstand before breaking.

The following is an actual account of aratameshi. This was documented by Takano Kurumanosuke in the mid ninetieth century - some swords performed bad, like very bad; but this example here was incredibly strong and testify that properly made Japanese swords were not fragile at all.

"(...) A katana by Yamamura Masao was also tested that day. The nagasa was a 65.15 cm.

Like the Naotane above, it had ara nie in the hamon. The Masao blade was used to cut wrapped straw eleven times and each cut went about 80 - 90% through the target.

Secondly, bamboo staffs were used for six cuts. Each cut penetrated 70 - 80% through the target.

Thirdly, an old piece of iron that was 0.303 cm thick and 2.12 cm wide was used as cutting object. The piece of old iron was cut in two pieces upon a single stroke of the sword.

However, ha-giri (nicks) may have developed. In the fourth step, deer antlers were used for six cuts.

The fifth test conducted was to cut straw wrapped bamboo twice and the cuts went in about 60%. Then 2 cuts each were executed on a helmet filled of iron sand, iron armor, and a shibuichi tsuba.

For the 9th and 10th test, a piece of forged iron and a kabuto were cut once each. Following that, an iron bar was used to hit the mune seven times and a mune-giri developed.

In the 12th and final test, the same iron bar was used to strike each side six times and the mune was used to hit an anvil thirteen times. The ha-giri became bigger upon the last test. The side of the blade was then used to hit the anvil three times and the blade finally broke in two."

(Source: Extreme Aratameshi)However, ha-giri (nicks) may have developed. In the fourth step, deer antlers were used for six cuts.

The fifth test conducted was to cut straw wrapped bamboo twice and the cuts went in about 60%. Then 2 cuts each were executed on a helmet filled of iron sand, iron armor, and a shibuichi tsuba.

For the 9th and 10th test, a piece of forged iron and a kabuto were cut once each. Following that, an iron bar was used to hit the mune seven times and a mune-giri developed.

In the 12th and final test, the same iron bar was used to strike each side six times and the mune was used to hit an anvil thirteen times. The ha-giri became bigger upon the last test. The side of the blade was then used to hit the anvil three times and the blade finally broke in two."

(Note: to avoid new myths spreading, no - the blade didn’t cut through armor! At best it was able to bite into it, create a dent and leave a mark but if there was a person behind it - would have been fine with no wounds:

An actual munition grade helmet with a minor dent caused by battlefield damage - either swords or more likely polearm strikes - that’s likely how the helmet looked like after being hit by a katana. The whole purpose of hitting armor was to test the blade strength rather than try to bypass it).

But what about bending the blade?

It is indeed true that a Japanese blade, if put under stress (i.e. bending), it will stay bent.

In fact, one of the main disadvantage of this style of hardening is that when you bend the blade, it won’t return to true like a spring . Due to this fact, many people see it as inferior (without even considering the benefits of a harder edge that I have pointed out before), but to be clear, differential hardening allows some vibrations in the blade:

It is indeed true that a Japanese blade, if put under stress (i.e. bending), it will stay bent.

In fact, one of the main disadvantage of this style of hardening is that when you bend the blade, it won’t return to true like a spring . Due to this fact, many people see it as inferior (without even considering the benefits of a harder edge that I have pointed out before), but to be clear, differential hardening allows some vibrations in the blade:

A recent cutting test done by Skallagrim with a Japanese sword hardened in the traditional way. As you can see, despite the blade being rigid, there is some flexion toward the tip during the cut. However, after that moment, the blade return to true without having a set or being bent.

So there is quite a lot of margin before introducing a permanent set in the blade. Moreover, spring tempered blades can take a permanent set as well! But they are quite hard to fix once it happened ( although it’s quite hard to bend them in the first place).

A quite famous video of Matt Easton trying to straighten a spring tempered antique blade. Here you can see that the blade was a little bit off.

A properly made high quality Japanese sword, if used as intended (not to cut stones for example) is not fragile at all. Actually, it was a blade capable of withstanding quite a lot of punishment and still being able to cut properly, much more compared to what a lot of people think.

But as an important note of this long myth, I would like to stress that swords are tools, and we could have good tools or bad tools, and they are not immune to failure or breaking, especially when used incorrectly. Swords broke all over the world throughout history, no matter what.

Yet the unrecognized ability of Japanese swords to withstand damage bring us to another myth:

Myth 7: "Japanese swords were never used in an armored context"

This most of the time read as "Japanese swords, and especially the katana, were not optimized to deal against armor; in fact, they were mainly used to cut down unarmored peasants running from the battlefield".

If you have spent some time looking online for this kind of information, you would have likely encountered that type of sentence, or a very similar one.

The educated versions read more like "Japanese swords were more a status symbol rather than an actual battlefield tool, and were rarely used on the field due to the poor performance against armor".

The aforementioned myth and the undeserved fame of being a brittle sword doesn't help either, and contribute to consolidate this view.

Some people actually go further in trying to justify such narration and came up with things like "Japanese armor wasn't good - it was mainly made of leather and bamboo, so the katana was perfectly fine to deal with that kind of "armor"". This is supposed to be a sword mythbusting article so I won't spend much word to it, but Japanese armor since the 14th century offered full body coverage and more so in the 16th century peaked with the development of the tosei gusoku (当世具足) style of armor.

To be fair, I can see why this myth originated and I have to say there is a little bit of truth, but it has to be put under the right context.

A lot of people used to think that the Samurai and the average warriors in Japan wielded their swords as their primary weapon on the battlefield; this of course wasn't the case, in fact as we know Samurai were first and foremost archer and later on they also became spearmen and arquebusiers, but pretty much they never wielded a sword as their primary weapon ( unless we are talking of nodachi - but that's definitely into polearm range).

A sword of normal size was a battlefield sidearm as well as a civilian life weapon, we all agree on that.Yet we can see that this correction has gone too far, and now we have the opposite claim: japanese swords were never used on the battlefield or against armor.

One of the several kawanakajima gassen zu byoubu (川中島合戦図屏風) depicting swords being used in battle against armor.

It is easy to see the design of Japanese swords (which are cut centric- hence optimized for the cut) and conclude that they are not good against armor.

While this is true, we should generalize and say that no sword all over the world in various culture were usually good against armor, and very few types of swords were actually optimized to bypass armor to some extent.

A sword is first and foremost a primary civilian life weapon, so it's quite obvious that is designed to perform better in a framework without armor.

However, swords were used on the battlefield, against armor as well.

Battlefield swords in Japan could sport a different edge geometry that allow the blade to cut against hard material like other swords and armors.

Said edge geometry is called niku -肉.

That geometry is really a trade off: you are increasing the angle of the edge, so the sword will be less sharp by design, but much more resilient on the other hand.

Moreover you will have a heavier blade with more mass behind the edge so it will increase the power of the cut; it will still cut but it won't pass through target as easily as without niku; all things considered, this is not a bad idea when armor is involved, since you don't want your weapon to be stuck into the enemy and to chip against armor.

Ideally, with any sword, you will try to hit unarmored zones: this on the battlefields all over the world was quite common at the end of the day since only a very small amount of warriors would have had a complete set of armor that covered the entire body.

Many soldiers that fought on foot historically didn't had extensive lower limb armor for example, because marching occupied 95% of their time on campaign and carriyng leg armor would have been a massive hindrance most of that time, and because given their rank and occupation, they weren't able to afford a complete set of armor as well.

In this scenario, cutting swords are still extremely viable and effective. We see that in many cultures as well.

This of course cannot be translated against heavily armored opponent; however, in this case there is a set of technique you can use to defeat armor: I have already talked about this here for the curious ones.

Not every type of Japanese swords could be used in this way for sure, and the majority of the target would be hands, armpit and face - not rigid armor.

It is in fact a common misconception that Japanese armor wasn't good enough or complete enough to justify a development towards anti-armor sword design - this is debatable since some Japanese sword design could be used in anti-armor techniques, but more importantly late Japanese armor was able to encase the wearer almost completely in plates and mail.

That's actually a common ground for heavy armored warriors in China, India and the Middle East. While we saw warriors clad in armor in those places, we don't really have anti armor sword design; and yet samshirs, dao and tulwar were used against heavily armored warriors clad in brigandine, mail and plates. The same apply for falchions and kriegmessers during the age of plate armor in Europe.

A Japanese katana that can actually be used properly in Japanese anti armor techniques.

Moreover, Japanese swords are blade heavy so they could still hit hard: this of course won't cause major damage against armor, and I want to underline that since the effect of blunt trauma against rigid armor (like the lamellar and later plate armors used in Japan) is very overestimated, a sword won't do much; but a solid hit against the side of the helmet, the hands, the elbow and knee region could still hurt the wearer and create an opening in the fight.

Moreover, during the heat of the battle, if you have lost your polearm and you are fighting in a tight formation, you don't really have many options than cutting and thrusting with your sword against every foes that try to approach you.

This problem of course is not present in case of horse fighting: the speed of the animal is sufficient enough to transmit a lot of force through a sword. It won't cut armor for sure but a sword hit received by a horseman can easily knock down and dent/damage armor as well as the wearer.

In this context, Japanese swords work perfectly fine against armor.

To conclude this point, we have account and depictions of sword used against armor both in the Kamakura as well as in the late Sengoku period, without specifically talking about Nodachi which were battlefield weapons optimized to deal with multiple opponents on horseback as well as on foot to deal against other polearms.

In fact, while the wrong idea of Samurai primarily being sword still persist, we shouldn't under stimate the importance and versatility of a sword even in a context with armor.

A sword, and especially a Japanese katana or tachi, is easy to carry and fast to deploy, has good defensive capabilities and has a long edge that allow all the weapon to be used with greater extent; you don't need to worry if somebody bypass the point of your sword for example, because you still have an entire blade: it's not the same with a spear, for example.

Those element are not present (or at least not as good as sword's ones) in warpicks or axes for example, that usually are depicted to be more suited against armor.

Yet people carried swords as their sidearm more often than axes or maces when heavy armor was around.

Myth 8: "Japanese swords were only used in Japan against Japanese techniques, tactics and armor".

However that was only the starting point; during the 14th and 16th centuries, more than 100 000 swords were produced and imported directly to Ming China as official gifts, and other swords were also imported to Ryukyu kingdom and Joseon Korea as well. Moreover, they actually spread all over East Asia due to those trade as well as the activity of Japanese pirates (wako - 倭寇) in between the 14th and 16th century.

The famous chiyoganemaru, a Ryuukyan sword manufactured in Japan, with local hilts and fittings.

Japanese swords were prized for their quality, manufacture and design in Asia and some we can find similar opinion on European sources from the 16th and 17th century, much before the all japonism movement started to be a thing. However it wasn't only a matter of exported items, the design was actually adopted into native swords in Korea, China and Vietnam, both in terms of longsword as well as greatswords: these are in fact called Chang Dao (長刀), Wo Yao Dao (倭腰刀), and we have similarities in some styles of Joseon Korean Hwando (環刀) and some types of Vietnamese sabers.

These swords were actually fitted with local and native styles hilt and guards, and often sported either an imported Japanese blade or a locally made imitation specifically designed after Japanese blades, with some native details.

In fact, across East Asia, Japanese blades were quite popular and used in various conflicts.

Thanks to the Japanese industry of the Sengoku period in terms of arms, armors and ronin, the Japanese themselves traded, fought as mercenary and moved their weapons and armor all over: it wasn't rare to see South East Asian warriors equipped with katana and Japanese firearms.

Funnily enough, an enquiry was received few years ago at the Royal Armories in Leed from a member of the public living on the site of the battle of Edgehill that took place during the English Civil War in 1642.

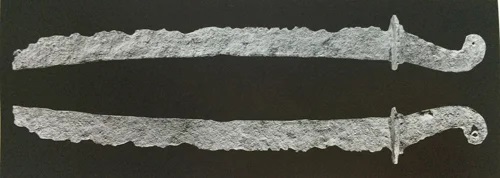

It involved the discovery of the very corroded remnants of a sword blade about 45 cm long, retained a well preserved copper habaki indicating that it was in fact a Japanese blade, almost certainly from a wakizashi. There is no positive evidence that the blade dated from the time of the battle, other than the amount of corrosion. If it was a genuine relic of that battle, someone who fought there was carrying a Japanese wakizashi. That's how far Japanese blades were used around the world in the 16th and 17th century - and not only for their artistic value.

Moreover, as I stated early, Japanese warriors fought abroad quite often in the 16th and 17th century: they were recruited as mercenary by the VOC to fight across their colony against native population or other European powers, and they fought in the famous Imjin war of the 1590s.

Those topics deserve dedicated articles and I won't have time here to cover all the citations and stories behind those Samurai who fought abroad, but those facts are enough to testify the quality of their blades and swordmanship.

So those blades were put to test in so many different context, against a wide variety of tactics, armors and fighting styles all over Asia. More often than not, those blades were prized and adopted by those native population as well, so the idea that Japanese blades stayed and were used solely in Japan is very far from the truth.

Myth 9: Length issues of Japanese swords

Probably a very common comment you might have already read, most of the time associated with katana, is the following: "Japanese swords (katana) are too short for their two handed usage".This also apply to tachi swords but with less frequency, and I have to say it's wrong on two main point of views.

The first one derives from the idea that reach is always a very important factor for swords and especially sword's fight. In this regard, the katana being a two handed sword lack the reach of other similar two handed swords, with a blade length in between 60 and 80 cm of length and an average of 70 cm.

Clearly, a 62cm blade katana is rather short for its two handed usage; but on the other hand, people usually forgot to take into account that a shorter blade would be easy to carry, hanlde and deploy in case of need. Those are advantages that are overlooked but might turn the odd of a fight in your favor, especially when the sword is supposed to be a self defence weapon in civilian life.

I would argue that in this scenario, a shorter weapon would be much better, all things considered, then a longer one.

However, this blade lenght figure is extremely biased.

On one hand, we should have in mind the context and the history of this particular sword; the uchigatana wasn't meant to be a longsword like the tachi up until the late muromachi period.

It started as a rather long one handed straight dirk that nowadays we would classify as wakizashi, and was a short backup sword for the low ranking troop of the late Heian and early Kamakura period.

Then it became the main back up weapon of the foot soldiers of the Sengoku period through the shape of the one handed katate uchi katana and finally reach tachi's lenght (so we are talking about 75-85 cm blade length, with some case of 90 cm blade length as well!) through the Azuchi Momoyama period, when it became the sword of the upper class as well.

In the context of pre-momoyama period, the katana was a short back up weapon either carried along a longer tachi for the mounted warriors or used as main sword for the foot soldiers that needed a fast to deploy sword and one long enough to be still used in close quarter formations.With this in mind, it make much sense for the katana to have its classical (short, if you will) dimensions.

Those late uchigatana however were very similar to the tachi of the period, with small differences in mountings and curvatures but not in lenght as they were meant to be war swords as well.

One might argue, "where are all of those long katana blades?" Because as a fact, most katana don't reach that blade lenght, and here there we have the strong aforementioned bias.

They were shortened and cut down to the tang in order to reduce their blade (and overall lenght). And looking to the amount of swords that went through this process, called suriage (磨上げ) or Ōsuriage (大磨上げ), it's an incredibly high number.

During the Sengoku period, longer swords didn't present an issue both in and out the battlefield, as we still have surving koryuu school that teach iaijutsu with blades as long as 90cm, which is nodachi lenght according to modern classification.

However, following the Edo period and the unification, swords started to be part of the civilian outfit of the Samurai, and according to the law of the period, the overall length of the weapon couldn't surpass 86 cm.

This meant that those longer blades were shortened and quite a lot in order to fit into the 86cm total length figure.

Old swords, unfortunately, and even nodachi were cut down to this "small length" so we are left with swords that don't have their original size anymore, and a very distorted historical average when it comes to dimensions.

So historically, while we have short katana that served their own purpose, we also had longer blades that were equally used in and out the battlefield that will very much eliminate the need of addressing this comment of t"he katana is a short two handed sword " if only these blades would have been preserved with their original size.

An original Uchigatana from the Sengoku period with interesting features: blade length of 80 cm, total lenght of 117 cm and a tsuba of 12cm diameter. This is quite impressive!

To be finished: "Myth 10: Japanese swords typology and lack of variations"

But as an important note of this long myth, I would like to stress that swords are tools, and we could have good tools or bad tools, and they are not immune to failure or breaking, especially when used incorrectly. Swords broke all over the world throughout history, no matter what.

Yet the unrecognized ability of Japanese swords to withstand damage bring us to another myth:

Myth 7: "Japanese swords were never used in an armored context"

This most of the time read as "Japanese swords, and especially the katana, were not optimized to deal against armor; in fact, they were mainly used to cut down unarmored peasants running from the battlefield".

If you have spent some time looking online for this kind of information, you would have likely encountered that type of sentence, or a very similar one.

The educated versions read more like "Japanese swords were more a status symbol rather than an actual battlefield tool, and were rarely used on the field due to the poor performance against armor".

The aforementioned myth and the undeserved fame of being a brittle sword doesn't help either, and contribute to consolidate this view.

Some people actually go further in trying to justify such narration and came up with things like "Japanese armor wasn't good - it was mainly made of leather and bamboo, so the katana was perfectly fine to deal with that kind of "armor"". This is supposed to be a sword mythbusting article so I won't spend much word to it, but Japanese armor since the 14th century offered full body coverage and more so in the 16th century peaked with the development of the tosei gusoku (当世具足) style of armor.

To be fair, I can see why this myth originated and I have to say there is a little bit of truth, but it has to be put under the right context.

A lot of people used to think that the Samurai and the average warriors in Japan wielded their swords as their primary weapon on the battlefield; this of course wasn't the case, in fact as we know Samurai were first and foremost archer and later on they also became spearmen and arquebusiers, but pretty much they never wielded a sword as their primary weapon ( unless we are talking of nodachi - but that's definitely into polearm range).

A sword of normal size was a battlefield sidearm as well as a civilian life weapon, we all agree on that.Yet we can see that this correction has gone too far, and now we have the opposite claim: japanese swords were never used on the battlefield or against armor.

One of the several kawanakajima gassen zu byoubu (川中島合戦図屏風) depicting swords being used in battle against armor.

It is easy to see the design of Japanese swords (which are cut centric- hence optimized for the cut) and conclude that they are not good against armor.

While this is true, we should generalize and say that no sword all over the world in various culture were usually good against armor, and very few types of swords were actually optimized to bypass armor to some extent.

A sword is first and foremost a primary civilian life weapon, so it's quite obvious that is designed to perform better in a framework without armor.

However, swords were used on the battlefield, against armor as well.

Battlefield swords in Japan could sport a different edge geometry that allow the blade to cut against hard material like other swords and armors.

Said edge geometry is called niku -肉.

That geometry is really a trade off: you are increasing the angle of the edge, so the sword will be less sharp by design, but much more resilient on the other hand.

Moreover you will have a heavier blade with more mass behind the edge so it will increase the power of the cut; it will still cut but it won't pass through target as easily as without niku; all things considered, this is not a bad idea when armor is involved, since you don't want your weapon to be stuck into the enemy and to chip against armor.

A pretty neat illustrations of niku; from left to right the degree of sharpness (from less sharp to very sharp) and toughness of the edge (from very resilient to less resilient). The hira zukuri is the sharpest by design, but the most fragile at the edge. With niku it would be the opposite.

Many soldiers that fought on foot historically didn't had extensive lower limb armor for example, because marching occupied 95% of their time on campaign and carriyng leg armor would have been a massive hindrance most of that time, and because given their rank and occupation, they weren't able to afford a complete set of armor as well.

In this scenario, cutting swords are still extremely viable and effective. We see that in many cultures as well.

This of course cannot be translated against heavily armored opponent; however, in this case there is a set of technique you can use to defeat armor: I have already talked about this here for the curious ones.

Not every type of Japanese swords could be used in this way for sure, and the majority of the target would be hands, armpit and face - not rigid armor.

It is in fact a common misconception that Japanese armor wasn't good enough or complete enough to justify a development towards anti-armor sword design - this is debatable since some Japanese sword design could be used in anti-armor techniques, but more importantly late Japanese armor was able to encase the wearer almost completely in plates and mail.

That's actually a common ground for heavy armored warriors in China, India and the Middle East. While we saw warriors clad in armor in those places, we don't really have anti armor sword design; and yet samshirs, dao and tulwar were used against heavily armored warriors clad in brigandine, mail and plates. The same apply for falchions and kriegmessers during the age of plate armor in Europe.

A Japanese katana that can actually be used properly in Japanese anti armor techniques.

Moreover, Japanese swords are blade heavy so they could still hit hard: this of course won't cause major damage against armor, and I want to underline that since the effect of blunt trauma against rigid armor (like the lamellar and later plate armors used in Japan) is very overestimated, a sword won't do much; but a solid hit against the side of the helmet, the hands, the elbow and knee region could still hurt the wearer and create an opening in the fight.

Moreover, during the heat of the battle, if you have lost your polearm and you are fighting in a tight formation, you don't really have many options than cutting and thrusting with your sword against every foes that try to approach you.

This problem of course is not present in case of horse fighting: the speed of the animal is sufficient enough to transmit a lot of force through a sword. It won't cut armor for sure but a sword hit received by a horseman can easily knock down and dent/damage armor as well as the wearer.

In this context, Japanese swords work perfectly fine against armor.

To conclude this point, we have account and depictions of sword used against armor both in the Kamakura as well as in the late Sengoku period, without specifically talking about Nodachi which were battlefield weapons optimized to deal with multiple opponents on horseback as well as on foot to deal against other polearms.

In fact, while the wrong idea of Samurai primarily being sword still persist, we shouldn't under stimate the importance and versatility of a sword even in a context with armor.

A sword, and especially a Japanese katana or tachi, is easy to carry and fast to deploy, has good defensive capabilities and has a long edge that allow all the weapon to be used with greater extent; you don't need to worry if somebody bypass the point of your sword for example, because you still have an entire blade: it's not the same with a spear, for example.

Those element are not present (or at least not as good as sword's ones) in warpicks or axes for example, that usually are depicted to be more suited against armor.

Yet people carried swords as their sidearm more often than axes or maces when heavy armor was around.

Myth 8: "Japanese swords were only used in Japan against Japanese techniques, tactics and armor".

I have encountered frequently the idea that "Japanese swords were mainly used in Japan" and never really saw actions outside a context in which shields, foreign armor and tactics were used.

This is often an argument made to justify the idea that said swords never really changed throughout history (which again it's false; more on this later), because simply there wasn't a need to improve due to the lack of foreign influences.

This is incorrect on several points; I won't deny that the main users of Japanese swords were indeed the Japanese (and the same could be said for every kind of sword related to a specific culture, like the European Longsword for example) but nevertheless, it is interesting to see that Japanese swords were put to test in different context and played a very important role in East Asian sword designs.

In fact, starting from the Mongol invasion of the 13th century, Japanese blades started to be tested against foreign armor - and actually no, they didn't break against Mongolian leather armor! (which by the way wasn't even the main form of armor of the Yuan invading army). The whole thing was a pure fictionalized version of the skirmishes fought in Kyushu that has no claim in original sources; to be fair, the Japanese gunkimono of the previous years usually overstate the ability of those blades, calling some swords double helmet cutters: while that's clearly an exaggeration it would have been totally silly to have the same swords chipping and breaking in the same kind of sources against rawhide armor.However that was only the starting point; during the 14th and 16th centuries, more than 100 000 swords were produced and imported directly to Ming China as official gifts, and other swords were also imported to Ryukyu kingdom and Joseon Korea as well. Moreover, they actually spread all over East Asia due to those trade as well as the activity of Japanese pirates (wako - 倭寇) in between the 14th and 16th century.

The famous chiyoganemaru, a Ryuukyan sword manufactured in Japan, with local hilts and fittings.

Japanese swords were prized for their quality, manufacture and design in Asia and some we can find similar opinion on European sources from the 16th and 17th century, much before the all japonism movement started to be a thing. However it wasn't only a matter of exported items, the design was actually adopted into native swords in Korea, China and Vietnam, both in terms of longsword as well as greatswords: these are in fact called Chang Dao (長刀), Wo Yao Dao (倭腰刀), and we have similarities in some styles of Joseon Korean Hwando (環刀) and some types of Vietnamese sabers.

These swords were actually fitted with local and native styles hilt and guards, and often sported either an imported Japanese blade or a locally made imitation specifically designed after Japanese blades, with some native details.

In fact, across East Asia, Japanese blades were quite popular and used in various conflicts.

Thanks to the Japanese industry of the Sengoku period in terms of arms, armors and ronin, the Japanese themselves traded, fought as mercenary and moved their weapons and armor all over: it wasn't rare to see South East Asian warriors equipped with katana and Japanese firearms.

A Javanese warrior equipped with Japanese weapons, from the Boxer Code.

Funnily enough, an enquiry was received few years ago at the Royal Armories in Leed from a member of the public living on the site of the battle of Edgehill that took place during the English Civil War in 1642.

It involved the discovery of the very corroded remnants of a sword blade about 45 cm long, retained a well preserved copper habaki indicating that it was in fact a Japanese blade, almost certainly from a wakizashi. There is no positive evidence that the blade dated from the time of the battle, other than the amount of corrosion. If it was a genuine relic of that battle, someone who fought there was carrying a Japanese wakizashi. That's how far Japanese blades were used around the world in the 16th and 17th century - and not only for their artistic value.

Moreover, as I stated early, Japanese warriors fought abroad quite often in the 16th and 17th century: they were recruited as mercenary by the VOC to fight across their colony against native population or other European powers, and they fought in the famous Imjin war of the 1590s.

Those topics deserve dedicated articles and I won't have time here to cover all the citations and stories behind those Samurai who fought abroad, but those facts are enough to testify the quality of their blades and swordmanship.

So those blades were put to test in so many different context, against a wide variety of tactics, armors and fighting styles all over Asia. More often than not, those blades were prized and adopted by those native population as well, so the idea that Japanese blades stayed and were used solely in Japan is very far from the truth.

Myth 9: Length issues of Japanese swords

Probably a very common comment you might have already read, most of the time associated with katana, is the following: "Japanese swords (katana) are too short for their two handed usage".This also apply to tachi swords but with less frequency, and I have to say it's wrong on two main point of views.

The first one derives from the idea that reach is always a very important factor for swords and especially sword's fight. In this regard, the katana being a two handed sword lack the reach of other similar two handed swords, with a blade length in between 60 and 80 cm of length and an average of 70 cm.

Clearly, a 62cm blade katana is rather short for its two handed usage; but on the other hand, people usually forgot to take into account that a shorter blade would be easy to carry, hanlde and deploy in case of need. Those are advantages that are overlooked but might turn the odd of a fight in your favor, especially when the sword is supposed to be a self defence weapon in civilian life.

I would argue that in this scenario, a shorter weapon would be much better, all things considered, then a longer one.

However, this blade lenght figure is extremely biased.

On one hand, we should have in mind the context and the history of this particular sword; the uchigatana wasn't meant to be a longsword like the tachi up until the late muromachi period.

It started as a rather long one handed straight dirk that nowadays we would classify as wakizashi, and was a short backup sword for the low ranking troop of the late Heian and early Kamakura period.

Then it became the main back up weapon of the foot soldiers of the Sengoku period through the shape of the one handed katate uchi katana and finally reach tachi's lenght (so we are talking about 75-85 cm blade length, with some case of 90 cm blade length as well!) through the Azuchi Momoyama period, when it became the sword of the upper class as well.

In the context of pre-momoyama period, the katana was a short back up weapon either carried along a longer tachi for the mounted warriors or used as main sword for the foot soldiers that needed a fast to deploy sword and one long enough to be still used in close quarter formations.With this in mind, it make much sense for the katana to have its classical (short, if you will) dimensions.

Those late uchigatana however were very similar to the tachi of the period, with small differences in mountings and curvatures but not in lenght as they were meant to be war swords as well.

A detail from the 豊国祭図屏風, showing people carrying long tachi during their daily life. From the early 17th century.

They were shortened and cut down to the tang in order to reduce their blade (and overall lenght). And looking to the amount of swords that went through this process, called suriage (磨上げ) or Ōsuriage (大磨上げ), it's an incredibly high number.

During the Sengoku period, longer swords didn't present an issue both in and out the battlefield, as we still have surving koryuu school that teach iaijutsu with blades as long as 90cm, which is nodachi lenght according to modern classification.

However, following the Edo period and the unification, swords started to be part of the civilian outfit of the Samurai, and according to the law of the period, the overall length of the weapon couldn't surpass 86 cm.

This meant that those longer blades were shortened and quite a lot in order to fit into the 86cm total length figure.

Old swords, unfortunately, and even nodachi were cut down to this "small length" so we are left with swords that don't have their original size anymore, and a very distorted historical average when it comes to dimensions.

Another detail from the 豊国祭図屏風 with long blades.

So historically, while we have short katana that served their own purpose, we also had longer blades that were equally used in and out the battlefield that will very much eliminate the need of addressing this comment of t"he katana is a short two handed sword " if only these blades would have been preserved with their original size.

An original Uchigatana from the Sengoku period with interesting features: blade length of 80 cm, total lenght of 117 cm and a tsuba of 12cm diameter. This is quite impressive!

To be finished: "Myth 10: Japanese swords typology and lack of variations"

Very nice, just skimming through it, I can already see that this would be an interesting read.

ReplyDeleteLet me share my experience of cutting steel plates with blade. I once cut a iron/steel plate with a blade I made myself, the blade had probably a 60 degree bevel, not that sharp and the quality of the blade is extremely, very soft.

The plate is probably of the same quality, but a bit harder.

What surprise me is the ease my blade cut through the plate. I hit it on the edge of the plate though, hitting on the flat side just dent the plate. The blade itself only had dent on the place where it hit and overall remain useful.

My opinion is that with same hardness a blade would have the advantage as it is object in motion vs one that remain still and from what I read, swords often have higher hardness than armor.

Thank you!

DeleteI think that it has already been shown that you can cut through thin steel plates even with bronze swords. It's quite possible, especially when you have a hardened edge. The problem is that often armor is not that nice as a thin layer of soft steel: usually it has deflective curvatures, it is work hardened or even hardened by quenching and tempering and is usually thick. You can actually dent softer armor, or even cut through them to some extent, however you need to be in very specific conditions to do that (like the one created during a "kabutowari" test).

But even in the best case scenario you will bite into the armor but not damaging the wearer since usually it's not close to the steel surface and the penetration would be minimal.

There are pictures online of damaged armor (probably either by polearms or spears) and they look like dents or small holes

I have an intriguing question since when I had seen the hardness of Medieval armor and Japanese sword.

DeleteJapanese sword could have a hardness of 800 VHP at its tip, while medieval 15th century armor, especially outside of Italy, have an average of 200s-300s VHP. I remember that

So could a Japanese sword, especially the one with the sharper tip, stab through the Medieval armor plate?

Also what is your opinion on why Japanese weapon is adopted throughout Asia?

I know they are effective, but why Japanese ones specifically?

Well, hardness is only one factors of so many things to consider when it comes to defeating armor. While it's true that a harder steel will have a easier time getting through a mild/soft steel plate compared to another softer steel, you have to consider the grain size of the material, its fracture toughness, it's thickness, the weight of the object, its shape, the speed and so on.

DeleteIf you ask me, you cannot penetrate armor, even if it's a 1 mm mild steel (150-200 VHP) armor plate, with any hand held powered weapon. And you have to consider that more often than not armor had very reflective shapes and was thicker than 1 mm so the amount of force required to bypass that is extremely high.

Not with a sword, maybe you could slightly punch through with a very heavy and pointed spear, but not anything serious.

I mean even couched lances more often than not didn't penetrate armor (although the harder ones - I'll bet you can pierce a munition grade cuirass with full speed on horseback).

A Katana doesn't have the mass, the shape nor the design to achieve such feat (and no other sword does, that's should be clear) and our body mechanics didn't allow to generate the amount of force required to force a steel blade through armor. if you would try do to so, you will very likely be deflected by the armor, which was designed to do that.

Why Japanese swords? Probably because back then only Japan had the economy to intensively mass produce weapons and selling them easily without the strict trade policies imposed by a central government, like Ming China. Moreover, and this should be said, because they were very good weapons and had a very good reputation.

Not only swords, but even armors were sold to Siam for example, and Spain in Manila acquired Japanese pikes and cannonballs as well through the late 16th and 17th century.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteFantastic post, i have here some old pics of japanese-influenced thai/siamese royal swords, could i share sending an email?

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! Feel free to share them if you want, my e-mail is: gunsen.military.history@gmail.com

DeleteSent

DeleteThank you so much! I will add them to this article ASAP! Thank you again

DeleteNo need for this or post will be saturated with images on a topic little addressed to this day, many questions would come next. Well the last time i checked Stephen turnbull's site:

Deletehttps://www.stephenturnbull.com/future-projects

"THE LOST SAMURAI: Japanese Mercenaries in Southeast Asia 1593-1698"

"AVAILABLE IN 2021"

as you already mentioned:

"Those topics deserve dedicated articles and I won't have time here to cover all the citations and stories behind those Samurai who fought abroad"

But if you had to pick only one, i believe king rama VII holding his japanese-influenced krabi sword would sound very cool. A symbol of how the friendly relations from a distant past transcend ages, even after death (sakoku times):

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan–Thailand_relations#History

I think one more picture won't be harmful, actually while it's quite well established that Japanese swords were used in China and Korea, Siam is hardly mentioned. Again, thank you so much for contributing to this blog!

DeleteI'm looking forward to read those books; honestly I don't really like Turnbull's books but I have to say that lately he seems to have adjusted his aim a little bit. No more supernatural katana, ninja and duelist samurai maybe? I will keep my expectations low, maybe the man would be able to surprise me.

But yes I would love to write something about those untold history, although it's hard to research as many documents are way too far from my reach.

The biggest reason would be that Chinese swords from the Ming dynasty started to follow Japanese influences ( though not only japanese), so it turns out to be difficult to tell apart what is really Chinese or Japanese in Southeast Asia

Deletehttps://www.mandarinmansion.com/article/chinese-long-sabers-qing-dynasty

very outside the scope of japaneseness, we get it:

https://khamphamai.com/uploads/0/post/guom-cua-viet-nam-thoi-xua-1.jpg

https://khamphamai.com/uploads/0/post/guom-cua-viet-nam-thoi-xua-2.jpg

http://archive.mandarinmansion.com/articles/vietnamese/dao-truong.jpg

http://archive.mandarinmansion.com/images/vietnamese/vietnamese-kiem-molar-grip/vietnamese-kiem.jpg

http://archive.mandarinmansion.com/vietnamese-kiem-straightsword

http://archive.mandarinmansion.com/images/vietnamese/vietnamese-kiem-with-ivory-hilt/vietnamese-kiem-straightsword.jpg

http://archive.mandarinmansion.com/articles/vietnamese/guom-truong.jpg

Two Vietnamese guőm truòng shown above. changdao or nodachi influences?..

https://www.mandarinmansion.com/glossary/guom-truong

obvious Chinese-influenced vietnamese saber on top:

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcSqcuJkIbxedU5zOOCh2lfwH8tr2HCvfZQrKLtDtnfA5Pi8jGhN

Chinese counterparts:

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcRZox3TomgcOfKU5x8si325X3ylv6K2W7XA-oL0U2SCPAFHvspB

Very true, there was a lot of common ground; once you have a Japanese inspired blade in China, it's easy to see this design adopted by other countries as well.

DeleteSorry for the late reply but blogger decided that your comment was spam for no real reason and I wasn't able to see it until now. But thank you again for your useful links!

I recall accounts by Qi Jiguang speaking very highly of Japanese swords. I believe these were nodachi due to the mentioned length(he says they were over five chi long which if I'm not mistaken is quite a hefty blade), but it does go to show that even against non-Japanese opponents with armor like the Ming that Japanese swords were still used to reasonably great effect.

ReplyDeleteQi Jiguang was one of the main advocate in favor of adopting extensively Japanese blades in his army, in fact he equipped his northern garrisons with Chang dao (adoption of Japanese nodachi) and his southern ones with swords resembling one handed katana. Funnily enough, given the relationship between Japanese swords and the famous general, Wo Yao Dao are also called Qi Jia Dao (戚家刀) which means sword of the house Qi in his honor, although he did not actually design the sword.

DeleteCertain Late Medieval European longsword typology actually came very close in concept of design with many Japanese swords. One particular typology popular throughout 15th century Northern Europe - considered to be one designed specifically to combat heavy armor: https://www.albion-swords.com/swords/johnsson/sword-museum-svante.htm

ReplyDeleteVery similar in idea in terms of thickness/distal taper, cross section, and point that is reminsicent of many chu and o kissakis.

So even in Western/Central Europe, there were different schools of thought regarding on which was the ideal sword design that could stand up in environments rich with heavy armor.

Not to mention certain falchions/hangers (so called "archer's swords" - could extend this to include some lange messer and dussack sabre typologies) that were widely popular among different classes of warriors. So people preferring to use stout sabres in armor rich environments also extend to Europeans as well.

That's very informative, thank you! I think that people gives too much credit to the idea that swords had always to keep it up with the top tier armor available. Even outside Europe in heavy armored context, swords were never really overspecialized to bypass flexible armor. If we think about the Ottoman Empire, that fought against European armor as well, we do not see the equivalent of estoc or such.

DeleteThis is true as well in the European context, where more often than not, the average sword was far from being heavily optimized to deal against the top tier armor of the period.

People also tend to forget that cutting power and capabilities are features that were prized back in the days, and having such anti armor design remove those features. Moreover, a blade very narrow and slender is not great to use as a defensive tool due to the point of balance and the mass, and those things are often overlooked when it comes to evaluating a sword.

If you have to use a sword on the battlefield, it might be helpful to have antiarmor features, but most importantly, it should be able to give you a good defensive "edge" against polearms and such.

Maybe with half swording a relatively narrow blade like an Oakeshott XVIII or an estoc can be used to parry things. Also, even with a "heftier" blade a static block against a polearm like poleaxe or a naginata in the japanese context is a really bad idea.

DeleteRedirect the attack is always the best option, even in sword vs sword fight.

You use the force of the opponent at your favor, while with a static parry you are basically stopping all the momentum. If your opponent is a fast thinker when his attack connects with your blade, he will change directions or something like that. A "fluid" parry is a better idea overall.

Or at least, this is what I learned in my years of Iaido and Aikido.

(repost)

DeleteActually, "heftier" blades (i.e. swords with forward blade presence, plus or minus stiffness) is what mainly assist swords being able to redirect blows effectively.

If we look at many Japanese swords, and especially the variety of Chinese dao and jian, their defense mainly revolve around pivoting about the point of balance, as well as manipulating it to move the sword about the wielder's body efficiently.

Trying to do the same with an estoc, smallsword, or a thrust centric rapier would feel very awkward, as they are balanced towards the hilt. It's good for moving the point around nimbly, but this feature would be disadvantageous in defending against longer heavier weapons - as most of the action would end up being around the hilt regardless due to inertia.

@Gunsen History

There is one discussion regarding the mentioned sword, in which HEMA practitioners also bring up the Albion Principe & Alexandria, mentioning how these swords types were likely designed to deliver powerful thrusts in armored contexts, while maintaining strong cutting ability: https://sbg-sword-forum.forums.net/thread/29137/albion-svante-second-edit-cutting?page=2

Hi again Gunsen!

ReplyDeleteJust wanted to pop in and continue to give my moral support for this series of articles and add some rambling thoughts/insights partially inspired by Shadiversity's katana myth debunking video he decided to poop out yesterday...

A couple of misconceptions that I've been noticing that might be worth addressing (maybe in an article on Odachi or something) is the notion that a katana/nihonto will be not as nimble/fast compared to a sword of identical length with a European-style tapering profile because of its thickness. As I mentioned in a previous comment, I have an odachi-like sword (i.e. a Miao Dao) of comparable length to a European longsword I have and one thing that surprised me about it is that it actually has a very similar weight, length and point of balance to my longsword and also handles very similarly to it. For reference, the longsword I have is Windlass's Sword of Roven while the odachi/Miao Dao is SBG's/Ryujin's Miao Dao which may not be accurate approximations of historical swords, but for the purpose of my comparison I'm assuming my swords are at least decent representations of their historical counterparts. Stats-wise, the Miao Dao's blade is only about 1.25 inch/3 cm longer than my longsword, it weighs about 4 ounces/113 grams more than my longsword, yet oddly enough it has a point of balance that's about the same and even slightly closer to the hilt than my longsword (6 inches/15 cm from the hilt for Miao Dao vs 6 5/16 inches/16 cm from the hilt for Longsword). I was wondering why this was the case and then realized something: the Miao Dao's handle is longer than that of my longsword which shifts the point of balance for the sword further back making it just as nimble as my longsword and this feature of extra long handles seems to be more common on Chinese/Japanese/East Asians swords when compared to their European counterparts. In addition, I looked at the back of my Miao Dao and realized it actually had more distal taper from base to tip than I thought (about 7 mm to 4 mm which seems to be within range of the tapering seen on some of the antique Changdao I've seen on Mandarin Mansion's website) which while not quite as thin as my longsword (about 4 mm to 1 mm) is still pretty drastic when considered in context. According to historical sources, the Miao Dao/Changdao is based on the Japanese Odachi, and I'm assuming the Ming Chinese made minimal or no changes to the weapon when adopting it to their own uses, but I'm not sure of this since the few Japanese museums with actual Odachi in them of comparable length don't seem to list blade width at back from base to tip in their online collections. I was wondering if you knew whether the sort of tapering I'm listing is in-line with historical antique Odachi of comparable length or whether that addition of tapering is something only unique to Changdao. By my reckoning, I'm guessing that it wouldn't be a-historical for that sort of tapering to occur since I have a replica katana with a comparable thickness (at the base at least) to my Miao Dao and I can't see why the Japanese wouldn't put that sort of tapering on an Odachi if they could...

In any case, good luck in continuing to improve this article and this blog! :) (because I feel like we really need it now that katana-bashers have become more common now and are arguably worse than the long dead katana cultists in regards to spreading myths! XP )

Sorry for the late reply, but thank you again for your insights!

DeleteOdachi had both distal (although quite minimal) and width tapers (called funbari) that aid with weight distributions, and as you noted since the handle is longer they could benefit from a better leverage as far as I know. Still, said weapons were quite unwieldy for the untrained soldiers and so usually the ricasso of the blade was wrapped with silk or leather. This was the first step towards the creation of the nagamaki.

But it is true indeed that more often than not Japanese swords, especially the long ones, are considered way more tip heavy than they actually are.

If I could join in, a article focusing on balance would be great as has been mentioned before I've also seen people say " katana are slow and are heavy meat cleavers" among other crap.

DeleteI had an argument with somebody who refuse to believe the Tang acted as a counterbalance,

" This is because additional length of the tang/handle are acting as the counterweight, making a large pommel unnecessary"

Source:http://www.tameshigiri.ca/2014/05/16/why-a-sword-feels-right/

I did find this interesting comment on Matt's katana vs. Longsword video he did like a month ago,

"Matt:Have you used a real Nihonto? They feel very differently from the replicas to be honest. More akin to a slightly heavier Iaito. Granted I have very little experience with these myself, only 2 Nihonto swinged actually, but the feeling is more balance towards the tsuka than the replicas. What do you think about this? Would this drive you to a different conclusion?"

Figured it was worth sharing.

There's also this video where he talks about not all medieval swords balancing the same way.

https://youtu.be/GAcdn7HQFDY

Also I think unwieldy would only be true with those super long Nodachi in the Nanbokuchō period.

Anyway yeah I think a discussion on balancing and how nimble a Japanese sword can be, would definitely be interesting.

I do believe that blade heavy sword on average do get this undeserved reputation, sadly. It's also true for early European medieval and migration period swords, which were much more blade heavy compared to later design - they are indeed considered unwieldy without proper reasons by a lot of people.

DeleteIf anything, the two handed hilt solve the issue quite well because you would be able to control the weapon fairly easy.

Japanese swords are far from being "machetes".

Hi Gunbai,

DeleteThank you again for your blog. Apologies I haven't had a chance to reach out to you again; I am in grad school and that has been consuming most of my time. I am, however, excited to finish up shortly and then get back to learning about medieval Japan.

Regarding the weight of Japanese blades: the evaluation of a sword being "blade heavy" can depend very much on the user and the style. I will say that, based on my experience in the martial arts, there is a big difference in effectively using the sword and wasting energy. Musashi specifically states that the sword must be swing strongly and with full extension, and illustrates that the sword is not an especially fast weapon. That does not mean it can't be used quickly and effectively, however.

I have had the privilege of wielding both modern swords and nihonto. In both cases there are a spectrum of weights and balances, and without understanding that there are good and bad quality swords in every culture, it's too easy to take a sample of one and assume that the entire category is homogeneous. For example: the nihonto I was fortunate enough to use was light and nimble in the hand, likely because it was a cut down sword that would have dated from far after the warring states period.

My main point is that technique and context is necessary to make the full use of any weapon. A backyard review of modern reproductions of dubious quality cannot be used to judge the use and utility of historic (or historically accurate) pieces.

This is very true, thank you for your input!

DeleteSwords are tools and despite sharing similar features within one category, they are all different, more so when it comes to pre-industrial technology were standardization was not really a thing.

Nimble and light nihonto existed as well, this is something worth to point out and generelization within one category will always yield poor results

Hi Gunsen,

ReplyDeleteSo I was wondering about something regarding "katate uchi": How long do their blades typically get and how short are their handles in relation to the blade? Was there ever a case where a katate uchi ever had a full length blade (i.e. 75 cm or longer) combined with a short handle that can only accommodate a one-handed grip (i.e. about 15 cm) to make a Japanese sword that somewhat resembles a dussack/saber/dao?

I ask because you mentioned the Chiyoganemaru and the Wodao/Woyaodao using Japanese-made blades and those swords seem to have proportions similar to what I'm describing, but they are Ryukyuan/Chinese swords respectively and are not exactly "truly Japanese" in a sense. Did anything like those swords ever become used on the Japanese mainland because it would be a bit strange that the Japanese clearly had the capacity to make "true" one-handed swords with full length blades (unlike wakizashi or kodachi) but didn't. Or did the so-called "uchigatana" more or less fill the role of "one-handed sword" but also just happened to have a long handle that could be used in two hands akin to certain messers or bastard swords?

As far as I know ( which might not be totally accurate), katate uchi were usually in between 60 to 68 cm in blade length and always had shorter tang and shorter handles so they could only be used one handed. It might be that 75cm blade katate uchi existed but usually it was under the 70 cm.

DeleteKeep in mind that some katana have a similar blade lenght, but a katate uchi was indeed a purely one handed sword.

When talking about the (uchi)katana itself, I think that this is the sword which best fit the term "bastard sword" in the sense that you can use it in both ways. Purely one handed sword existed but were on the short side, as most of the warriors of the period preferred to use the longer two handed versions which could go furhter than 75 cm blade length as well.

Friendly reminder you have not finished Myth 10.

ReplyDeleteXD

You are right! I hope to get back to track into this one soon :'D

DeleteHi again Gunsen!

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I was thinking about Japanese sword typology recently and was wondering about the origins of the weird modern classification of Japanese swords e.g. uchigatana vs. tachi and whatnot, and did some digging and stumbled across an interesting image that I wanted to share and also to ask about something since it's outside my knowledge. I was looking at images of the Aizu Kage Ryu scroll housed in the Tokyo National Museum and apparently there is a scroll that seems to have an old classification system for Japanese swords (i.e. the 3rd scroll in the picture): https://i.pinimg.com/originals/b2/93/a4/b293a4796386d29a5840c770e821db3e.jpg

I tried to see if I could find if anyone attempted to transcribe the text of the last scroll and sure enough I did: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/138643648

It seems that the last scroll has the following text:

"仕相之太刀

一のべたち

一はねたち

一ちのたち

一前ひろ

一はつしきり

一しやうのかかり

勝太刀之切相(口傳おゝし) "

The kanji/hanzi of the first titular text, "仕相之太刀," or "Official Forms/Appearances of the Tachi" seems to be implying that all the weapons depicted are forms of "tachi/太刀/たち" including the large nagamaki-like weapon in the first picture and the smaller looking swords in the later pictures. It also seems to give names to all the different types of swords in hiragana. My knowledge of Japanese is limited, and I just wanted to know if you knew how to translate the text or could provide any insight on it, but after plugging in the text into various translators, I came to a few guesses on what's going on. If you can correct me on anything, it would be greatly appreciated.

It seems to me the first three types of tachi/swords are called, nobe-tachi, hane-tachi, and chino-tachi. The "nobe/のべ" in nobe-tachi can correspond to the kanji "野辺" meaning "field" which means that "nobe-tachi/野辺太刀" is another way of saying "nodachi/野太刀" for the nagamaki-like weapon which makes sense if you ignore the "common sense" that nodachi and odachi are just different names for the same type of sword and that the proper name for the weapon depicted is nagamaki/長巻. The "hane/はね" in hane-tachi can correspond to the kanji 羽 meaning plume/feather/wing which means that the second odachi-like weapon's name in kanji seems to be 羽太刀 meaning "feather tachi" which makes sense if you consider the shape of various odachi blades. The third one's got me a little stumped, since I couldn't find a good translation or kanji meaning for "ちの" but a bit of a crazy guess is that if we take the "の" here to be understood as the prepositional possessive/descriptive の particle, and the "ち" as a potential shortening of "うち/打/uchi" then the term chi-no-tachi/ちのたち could be understood as (う)ちのたち/uchi-no-tachi or "striking tachi" i.e. another way of saying "uchigatana/打刀" which would make sense for the seemingly shorter two-handed sword depicted.

Anyway, I admittedly suck at Japanese and the rest of the text I can't make heads or tails of and would love to see yours or anyone else's insights on this who are more well-versed in the language.

Hope you're well, happy holidays, and hope you can find time to continue working on the blog (and the long overdue Myth 10 of this article! ;) )

Sorry! One more thought that occurred to me that you can feel free to correct me on because I thought of it for the 3rd sword while reading through a Japanese dictionary: Could it be that the term "uchigatana" aka "(u)chi-no-tachi/(う)ちのたち has been misunderstood by everyone to be 打ち刀 aka 打ちのたち when instead it's supposed to be 家(の)刀/家(の)太刀? It seems that "ち" could correspond to the "家" kanji meaning "house" which makes sense since it's a shorter longsword that could be carried in the house? Again, I suck at Japanese and would love to hear other peoples' insights.

DeleteHi and thanks for the sources!

DeleteThat's indeed quite a lot of nomenclature going on. To be fair I think that you went quite far into your interpretation and I'm quite amazed becuase indeed it make sense, so you might have nailed it. However, I'm not that proficient enought to tell you if you are correct on the matter. What I can say is that 99% of the time the の is used as 之 and works as the usual Japanese proposition of possesion "of".

Keep in mind that schools had their own languages and definitions, and language changed as well. Even going back to the late Edo period, in the 19th century, you have some visual dictionaries of arms and armors, and not surprisingly words such as nodachi or nagamaki are written with different kanji. I do suspect that we are in a very similar case, with nomenclature specific to that school being used to refer to something that we would know with other names.

The Edo period didn't help with its obsession of labelling old stuff with new names: for example, the word we refer to haramaki in period sources was used to refer to do maru before Edo. So going back to period sources with pre modern terminology might create some puzzles.

Tachi might be well used as "great" sword in sense of beauty and importance rather than length, and for example the word nodachi was used in Heian period sources to imply "field swords" as to sword meant for battle rather than parade/display, not the massive great swords used in later period.

What I can suggest to make the puzzle a bit clear when it comes to Japanese swords terminology is to read visual dictionaries of Markus Sesko. I used them myself and I think he did a great job in making some order for the english readers.

To your last point, uchi also refers to the ability to quickly strike in case of need, or at least is implied into the idea of "striking". Things like the katate uchi were indeed mean to be used with one hand (katate) to strike.

The word 家 is mostly used to refer to household as family rather than the building itself, at least when is associated with swords. When we refer to stuff meant to be used in houses we usually see the word makura being used - at least with spears.

Hello (yet again!)